Biden was a senator for 36 years and vice president for eight. His response was essentially that the questioner was cherry-picking two decisions and ignoring everything else in his record. What about his role in bringing down Slobodan Milosevic or his advice—ignored by Obama—not to surge troops into Afghanistan in 2009 or his rallying NATO to confront Russia over Ukraine?

On Iraq, Biden gave a familiar answer that Democratic senators who voted for the invasion have been making for 17 years: It was a vote to give President George W. Bush leverage at the United Nations to bolster a weapons inspection regime, not to greenlight an imminent attack. (This is historically accurate, but a bit like arguing you let a college-aged friend borrow your credit card only for buying books for his fraternity and then being surprised about all the pot and booze he added to the bill.)

On the bin Laden raid, Biden, changing his story a bit, insisted that after a larger meeting at which he expressed reservations, he privately told Obama to go for it. (During his lengthy response, at one point, Biden accidentally said Saddam Hussein when he meant Osama bin Laden.)

Despite the tough question, Biden seemed pleased. If the subject is foreign policy, Biden believes he’s winning. He’d rather talk for hours defending his worst foreign policy blunders than spend a minute focusing on, say, busing or bankruptcy reform. “It’s not to suggest I didn’t make mistakes in my career,” he told the young questioner in Des Moines. “But I will put my record against anyone in public life in terms of foreign policy.”

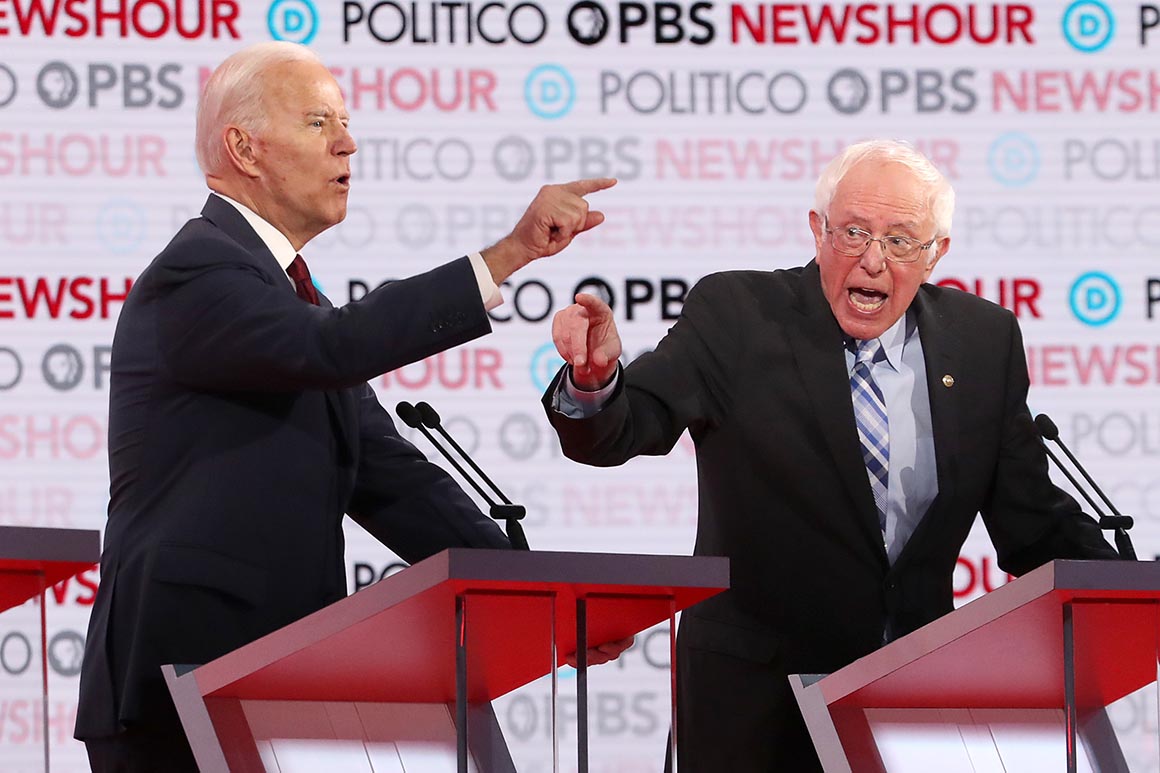

Bernie Sanders was the only rival who seemed to welcome that challenge. While Biden’s strategy is that of a traditional primary frontrunner—ignore your primary opponents and focus on your general election opponent—Sanders has the classic strategy for the person in the No. 2 spot: argue it’s a two-person race.

In Iowa last weekend, where there were dozens of candidate events, Sanders was the only other politician who seemed to relish discussing the confrontation with Iran — and how the Iraq War and the Democrats who supported it helped bring about the current situation.

“What Iran has done is really highlighted both Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden as representatives of two different poles in the Democratic Party: one a much more hawkish interventionist arm of the party, which used to be dominant, and then Bernie Sanders, representing a more diplomacy-oriented approach, a more collaborative international approach that is ascendant in the party,” said Jeff Weaver, one of Sanders’s top advisers, who went on to ding Biden for the 2002 Iraq vote.

The common assumption about Democratic base politics has been that the domestic trumps the international, that voters in Dubuque would rather hear about how candidates are going to fix their health care than about how they’re going to fix the Middle East.

But that’s not entirely true. Every open Democratic primary since 9/11 has been about war, and the beneficiary of the debate over that issue hasn’t been easy to predict. In 2004, another insurgent Vermonter — Howard Dean — based his entire candidacy on his opposition to Bush’s invasion of Iraq, which was enormously unpopular among Democrats and which John Kerry had voted to authorize. Kerry, after struggling in 2003, when Dean’s antiwar message thrilled liberals and filled stadiums, easily defeated his New England rival when voting began in 2004.

In 2008, Barack Obama’s opposition to the Iraq War was perhaps the single most important argument he made to show voters that, according to the two buzzwords of the primary, his “judgment” was superior to Hillary Clinton’s “experience.” By then, voters had grown tired of the body bags coming home from Baghdad and Kandahar, and the politics of the wars had ricocheted against the Republican Party and hawks like John McCain. But Obama soon made it clear that voting to invade Iraq didn’t disqualify Democrats from governing. He chose Biden, who, like Clinton, voted to authorize the war, as his running mate and made Clinton his secretary of State. In the 2016 Democratic primaries, Sanders was unable to run the same play against Clinton. He frequently highlighted her Iraq vote to no avail.

This election, 2020, seemed like it might be different. But Iran has belatedly forced a serious foreign-policy debate among the major Democratic candidates, with Sanders and Biden representing opposite sides of a basic question that could define the next administration: What do Democrats believe about America’s role in the world? And do they have a national-security message that can defeat Trump’s chest-thumping bravado?

***

Earlier on the same day Biden spoke, Sanders stumped in Grundy Center, about 90 minutes northeast of Des Moines. It was a small working-class audience and Sanders, after blasting Biden on Iran for the cameras, returned to health care.

Though the term is not often used nowadays, the Sanders town hall format is what sixties-era activists used to call “consciousness raising.” He prods ordinary people to stand up and describe for their fellow citizens the depravities they’ve experienced in the American health care system. Older radicals used the method to make working people aware that they were oppressed, that they weren’t the only ones, and that they could do something about it.

These sessions usually surface so many sad stories that Sanders has a regular joke about how his wife, Jane, complains that his events are too depressing. He then points to an aide who will be handing out Prozac on the way out.

The Sanders view is that, quite literally, this is how the revolution starts. Raise enough consciousness among regular people about the vagaries of the health insurance industry and eventually people will be organizing together and clamoring to trade in their own insurance plans in favor of “Medicare for All.” This is not just how Sanders sees health care, but it’s how he sees almost every issue, including foreign policy.

“I was mayor of the city of Burlington, Vermont, in the 1980s, when the Soviet Union was our enemy,” he said in a 2017 address at Westminster College, in Missouri. “We established a sister city program with the Russian city of Yaroslavl, a program which still exists today. I will never forget seeing Russian boys and girls visiting Vermont, getting to know American kids, and becoming good friends. Hatred and wars are often based on fear and ignorance. The way to defeat this ignorance and diminish this fear is through meeting with others and understanding the way they see the world. Good foreign policy means building people-to-people relationships.”

But how that commendable insight translates into policy has been a struggle for Sanders to articulate.

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream