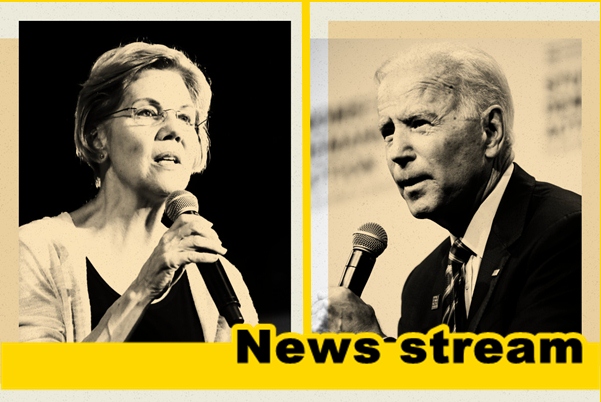

As Elizabeth Warren battled Joe Biden over a bankruptcy bill more than a decade ago, she confided her frustrations with the Delaware senator to a progressive ally.

Then a Harvard law professor with a limited national profile, Warren had publicly accused Biden of siding with creditors over middle-class Americans drowning in medical debt and credit card bills.

But Warren — who had become a Democrat only in 1996 — also privately described Biden as part of what was wrong with the party.

“She said something like ‘As long as people like Joe Biden are heading the party, there’s no one looking out for the little guy,’” the ally recalled, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Warren ultimately lost the fight over the bankruptcy bill. But now, the two Democratic presidential contenders’ divergent world views are set to be aired in prime time next month when they meet on a presidential debate stage for the first time.

As two of the top-polling candidates, they’ll be standing together at the center of the debate stage in Houston — a situation they dodged in the first two debates, when they were randomly assigned to different nights.

The showdown has been a long time coming. For years, Warren has seen Biden as emblematic of a Democratic Party that’s too cozy with big corporations, according to interviews with several longtime allies.

During the fight over the bankruptcy bill, Warren wasn’t shy about attacking Biden by name.

In 2002, she published an op-ed in The New York Times in which she insinuated that Biden had bowed to the pressure of banks and credit card companies in his home state to support the bankruptcy bill. The legislation, she argued, would keep people who needed to file for bankruptcy from doing so, telling The Washington Post those who supported changing the law “are the same people who would have said during a malaria epidemic that the way to cut down on hospital admissions is to lock the door.”

Another ally said that when Warren speaks about coming to Washington and realizing the majority of Democrats aren’t her allies, “she’s talking about Democrats like Biden.”

“Their experiences, their attitudes are very different,” said Mike Lux, who served as national deputy political director on Biden’s 1988 presidential campaign and later worked with Warren. “Elizabeth came up through the progressive movement ranks, and Biden came to town a long time ago and is very much a part of the old school in the Senate.”

Their differences go beyond the fight over the bankruptcy bill. In 2016, Warren was one of a handful of senators who voted against a health care bill that included funding for a cancer “moonshot” initiative named for Biden’s son, Beau, who died of brain cancer in 2015. Biden called a vote to move forward with the bill over which he presided “maybe one of the most important moments in my career.”

Despite their history, Biden’s campaign played down expectations for a potential clash with Warren.

“As Joe Biden said himself, he has deep respect for Elizabeth Warren,” Andrew Bates, a Biden campaign spokesman, said in a statement to POLITICO. “His campaign is not focused on running against any of the other candidates, but on making the case that he has an unparalleled record of delivering progressive change and that he is the best person to defeat Donald Trump and the atrocious values he represents.”

Warren’s campaign declined to comment.

But the two candidates have subtly jabbed each other in recent days. Biden’s campaign implicitly criticized Warren for not attracting as much support from voters of color, while Warren last week chastised Democrats who want to “just turn back the clock” and “make change incrementally.”

They also have sharp differences on policy issues. Warren backs Bernie Sanders’ “Medicare for All,” proposal while Biden has called for adding a public option to Obamacare — an issue that’s likely to come up on the debate stage. Warren has also called for breaking up Facebook and other big tech companies, which Biden hasn’t embraced, and for repealing most of the 1994 crime bill, which Biden helped write.

Warren has described the fight over the bankruptcy bill as a formative political experience.

Melissa Jacoby, a University of North Carolina law professor who served with Warren on the National Bankruptcy Review Commission in the 1990s, said Biden’s “need to protect his corporate constituency may have been blocking his ability to hear the reality of the situation.”

Biden has defended his vote for the bill, which passed in 2005, as a way to secure consumer protections in a bill that was likely to pass the Republican-controlled Congress, anyway.

But he doesn’t appear to have held a grudge against Warren over her criticisms of him.

The next time they saw each other, Biden “held out his arms and shouted from halfway across the room, ‘Professor! Come here and give me a hug!’” Warren recalled on the Senate floor in 2016.

“He had not forgotten our earlier battle, but he made it clear that he continued to think and rethink issues about working families and that, even when we disagreed, we could respect — and even like — each other,” she said, adding that Biden had “provided encouragement, wisdom and good counsel time and again.”

As vice president, Biden supported Obama’s decision to appoint Warren as a presidential aide charged with helping set up the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Terrell McSweeny, who was Biden’s domestic policy adviser at the time, said in an interview.

Warren also advised the administration’s Middle Class Task Force, which Biden led, and wrote a post for its blog outlining how the new agency would help families.

“I never recall him having anything other than respect for her,” McSweeny said.

After Biden administered Warren’s oath of office in 2013, he pulled her close. “You gave me hell,” Biden told her in an apparent reference to the bankruptcy bill, as Warren and her husband, Bruce Mann, laughed, according to C-SPAN footage of the event.

Biden even considered Warren as a potential vice presidential pick in 2015 as he weighed running for president. Warren told him at the time that she thought his past positions on issues like bankruptcy would make it harder to run to Hillary Clinton’s left in the primary.

Warren and Biden found themselves at odds again in the final days of the Obama administration, as Biden worked to steer a health care bill called the 21st Century Cures Act through Congress. Warren decried the bill as full of too many giveaways to the pharmaceutical industry.

“When American voters say Congress is owned by big companies, this bill is exactly what they are talking about,” she said in a speech on the Senate floor.

She accused Republicans of holding funding for the opioid crisis and Biden’s cancer moonshot initiative “hostage unless everyone agrees to special favors for campaign donors and giveaways to the richest drug companies in the world.” She was one of only five senators to vote against the bill, along with Sens. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.), Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), Mike Lee (R-Utah) and Sanders.

While it’s unclear whether Warren will go after Biden on the debate stage, she’s hinted on the campaign trail that she’s not afraid to talk about their old disagreements.

“At a time when the biggest financial institutions in this country were trying to put the squeeze on millions of hardworking families who were in bankruptcy because of medical problems, job losses, divorce and death in the family, there was nobody to stand up for them,” Warren told reporters in April. “I got in that fight because they just didn’t have anyone. And Joe Biden was on the side of the credit card companies.”

By THEODORIC MEYER and ALEX THOMPSON

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream