Joe Biden, whose debate performances previously had been characterized by his perplexing habit of stopping mid-sentence before his time expired, repeatedly scolded the moderators for leaving him out. Mike Bloomberg, who at times seemed to be casually watching the debate from the sideline last time, eagerly thrust his hand into the air and jumped into the fray more often this time. Pete Buttigieg and Elizabeth Warren, always the most eager to jump in, were as aggressive as ever. Amy Klobuchar and Tom Steyer, who often seem to get shorted at debates, repeatedly seemed frustrated about getting left out of key exchanges.

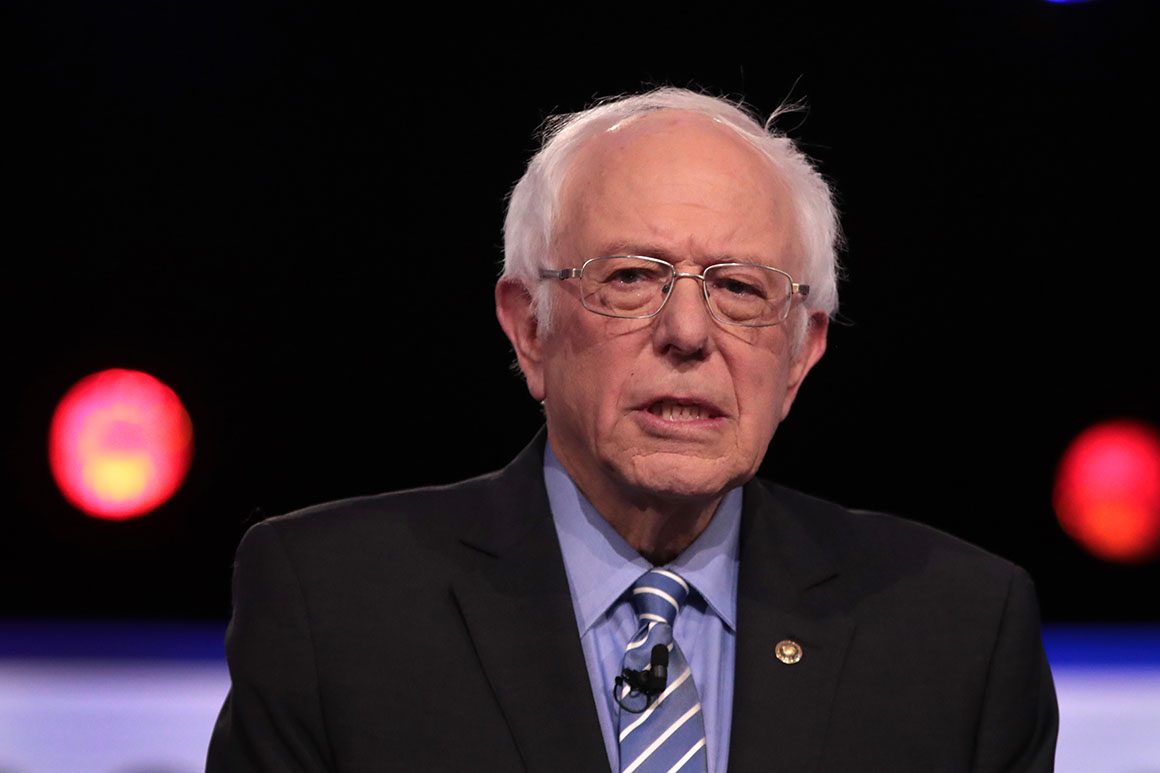

They all seemed more desperate and more manic during their final primetime chance to make the case against Sanders before a majority of delegates are chosen starting on Saturday and then on Super Tuesday.

That case against Sanders was clarified but not fully prosecuted. By the end, it was clear that there was no Bernie slayer at the lecterns in Charleston, someone who alone had the time and skills to convince Democratic voters that the democratic socialist was a radical whose nomination would forfeit the party’s chance to defeat Trump.

This was not quite a kitchen sink debate where everything is thrown at the frontrunner, but more of a distillation of several strains of attack unique to each of Sanders’ opponents.

Bloomberg began the evening with what might be described as the cheap shot approach. At the last debate, in Las Vegas, he called Sanders a communist. At the Charleston debate, Bloomberg tried to use Russia’s alleged pro-Sanders disposition to discredit him. “Vladimir Putin thinks that Donald Trump should be president of the United States,” he said, “and that’s why Russia is helping you get elected.”

Later Bloomberg tried to jab at Sanders over the senator’s comments praising Fidel Castro’s literacy and health care programs, which Sanders defended again on Monday in an interview on CNN. Bloomberg proved to be a poor messenger. Sanders, in a bit of red-baiting jujitsu, threw back in Bloomberg’s face the former mayor’s own pro-China comments, which he similarly reiterated on stage when asked. “I was amazed at what mayor Bloomberg said a moment ago,” Sanders said. “He said that the Chinese government is responsive to the Politburo, but who are they responsive to?”

At best, an issue that was supposed to be devastating for Sanders was a draw. The episode is reminiscent of a moment in the 2008 Democratic primary campaign when Barack Obama defied the foreign policy establishment and frustrated Hillary Clinton’s campaign by defending rather than retreating from his supposed gaffe about meeting with the leaders of Iran without preconditions.

Later, Obama’s top advisers, some of whom are now highly skeptical of Sanders, proudly pointed to that moment as a turning point in the campaign that highlighted Obama’s willingness to stand up to the kind of national security conventional wisdom that led Democrats to take misguided hawkish positions on issues like Iraq.

They are much further to the left than the Obama crew, but the group of progressive foreign policy advisers around Sanders define themselves by their willingness to defy the certitudes of Washington’s foreign policy establishment, which they derisively call “the blob,” and Sanders made it clear he will not apologize for his Cold War heresies.

It might be a good bet. The Obama opening to Cuba was in 2014 (and since reversed by Donald Trump). Castro died in 2016. It’s true that Florida’s older Cuban-American community, which remains politically influential, is deeply unfriendly to politicians who focus on Castro’s literacy programs at the expense of his crimes. But the idea that it’s politically deadly in 2020 to articulate a more nuanced assessment of the communist dictator’s reign than what was politically acceptable during the Cold War and its aftermath is dubious.

Not only has time eroded the salience of the issue, but so has the last two decades of changes in communications and trust in elite institutions, which no longer control the acceptable bounds of American foreign policy on issues like Cuba. Trust in elites has been plummeting since the turn of the millennium, and Sanders has been both a catalyst and a beneficiary of that collapse.

If Bloomberg is supposed to be the Democratic Party’s Bernie slayer, he came to Charleston looking more like Joffrey Baratheon than Gregor Clegane.

If Bloomberg’s case against Sanders is overly aggressive, Warren’s is characterized by being subtle almost to a fault. She has tried to make the argument that she is a more effective senator and someone who understands how to use power to achieve tangible results, not just secure a politically pure voting record. But she was sometimes reluctant to even mention Sanders by name. One of the ways she has tried to distinguish herself from him is by noting that she supports getting rid of the filibuster and he doesn’t. Besides being a fairly high-concept process issue that is not on any lists of voters’ top concerns, Warren was reluctant to forcefully confront Sanders over it, saving her fire for Bloomberg.

“Understand this: Many people on this stage do not support rolling back the filibuster,” she said. “Until we’re ready to do that we won’t have change.” Her goldilocks strategy of making fine distinctions between her and Sanders that don’t sting too much might look quite good in hindsight if he wins and she ends up being chosen as his running mate, but they are puzzling at the moment when the obvious mission is to stop him.

The three moderates — Biden, Buttigieg, and Klobuchar — while joining various Sanders pile-ons, focused mostly on the astronomical cost of the Sanders agenda and his refusal to detail how he will pay for it. This line of attack seemed more fruitful than either dusting off old quotes from the Cold War or debating parliamentary procedure.

Sanders has glided through a year of campaigning churning out enormously ambitious and expensive federal policy proposals with little regard to the costs. The total now is estimated to be $60 trillion. When the pressure to cough up some more numbers increased this week, his campaign put out a list of pay-fors that did not come close to matching the scale of his spending. For instance, he identified less than $18 trillion in revenue for his Medicare For All plan, which he estimates will cost $30 trillion and outside estimates peg at much higher.

“The math does not add up,” Klobuchar said, noting that his plans would cost more than three times the size of the entire American economy and reminding voters that back in the fall it was no less an authority on winning a general election as a Democrat than Barack Obama who warned about proposing ambitious plans that are beyond “where the voters of this country are.”

After Klobuchar delivered her lines, several candidates — Klobuchar, Buttigieg, Steyer, Sanders, Biden—descended into a free-for-all as they each attempted to get a word in and two moderators tried to gain control of the conversation.

Steyer pleaded, “Let me go!”

Buttigieg pleaded, “Let’s talk about math!”

Biden yelled, “Hello?”

Somewhere in the middle of it all Sanders, who seems to have survived what was for him the most precarious debate of the campaign, blurted out “not true!” and eventually they all moved on to the next topic.

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream