Within hours, via press releases, media hits and coordination with other groups, they had made their point: President Donald Trump’s decision to kill Qassem Soleimani was a mistake, and the U.S. needed to de-escalate the tensions.

“It was a heavy and anxiety-filled moment but also an exhilarating one,” said Jessica Rosenblum, the institute’s communications director. “We looked at each other – virtually speaking – nodded agreement, and put our heads right back into the work.”

The Quincy Institute, which formally launched in December, is not without controversy. But its mere existence is emblematic of how much faster, more organized and more popular the anti-war – or “war-skeptic” – movement is today compared to the early 2000s, especially as the U.S. prepared to invade Iraq.

Nearly two decades of fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq have soured many Americans, including military veterans, on wars that grind along consuming lives and resources but never seem to end. The failure to find weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and the mounting costs of the wars have also bred public skepticism, skepticism deepened by Trump’s own credibility problem, with observers quick to question his administration’s claims of an “imminent threat” from Soleimani. And Democrats who once feared being painted by Republicans as unpatriotic if they criticized a president’s national security moves now feel emboldened to speak up.

This changed political environment is surely not the only, or even the primary, reason why Trump has sought to calm things down after Iran struck back with a barrage of missiles. And some GOP lawmakers certainly haven’t hesitated to portray Democrats as practically in league with terrorists.

Yet the rise of organizations and networks like Quincy raises questions not only about whether that kind of scorched-earth rhetoric still works in American politics, but also whether it augurs a United States newly constrained in world affairs by the weight of its own experience.

“It’s sometimes incorrectly called war fatigue, but it’s also wisdom,” Stephen Miles, executive director of the group Win Without War, said of the country’s present mood.

Grassroots on fire

Miles’ group itself is an example of how things have changed.

Win Without War was launched by a coalition of civic and religious leaders in late 2002, as then-President George W. Bush’s administration was arguing the case for invading Iraq. At the time, it was called “Keep America Safe: Win Without War.”

Its founders called themselves “patriotic Americans who share the belief that Saddam Hussein cannot be allowed to possess weapons of mass destruction,” but who feared a U.S. invasion would “increase human suffering, arouse animosity toward our country, increase the likelihood of terrorist attacks, damage the economy and undermine our moral standing in the world.”

For most of its history, Win Without War had two to three staffers. Today, the group boasts 10 full-time staffers with plans to add more; in the last four years, its email list has grown from around 50,000 to half a million. Much of that growth has coincided with Trump’s rise.

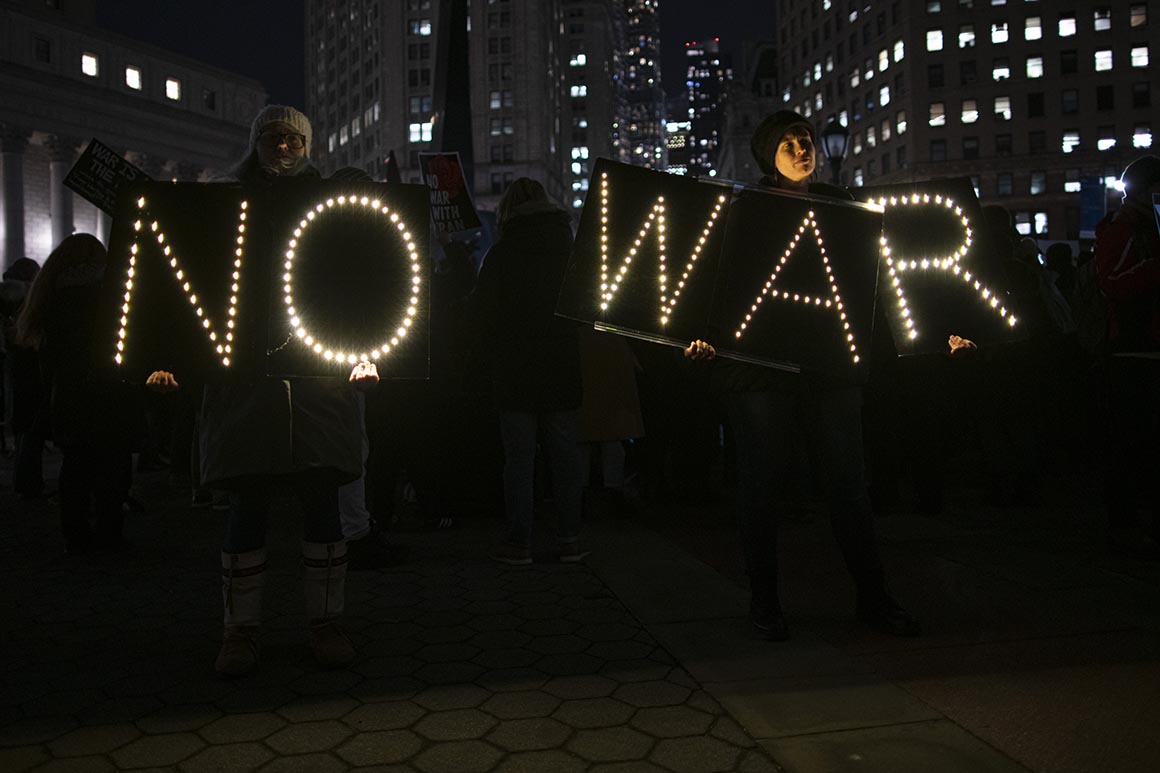

Win Without War, along with allied progressive groups such as MoveOn, helped organize more than 370 “no war with Iran” events and actions nationwide on Jan. 9, a week after Soleimani was killed and days after Iran retaliated by firing missiles at bases housing U.S. troops in Iraq.

Although the situations aren’t perfectly analogous, in the early 2000s, it took months for the anti-war movement to gain steam. That was in part because then-President George W. Bush and his team took time to make their case to invade Iraq after already going into Afghanistan. Major protests against an Iraq invasion were held in October 2002 and February 2003.

But it’s also because public opinion moved more slowly back then. Rahna Epting, the executive director of MoveOn, pointed to advances in technology, including the growth of social media, as a key reason groups like hers can organize more effectively than two decades ago.

Within 24 hours of the U.S. strike on Soleimani, who was visiting Baghdad at the time, MoveOn had galvanized thousands of its supporters to call members of Congress and urge them to “rein Trump in” and de-escalate, Epting said.

At the time “we were hoping the Iranian regime was reasonable, which I can’t imagine what day of my life that seems like a good position to be in,” said Epting, who is of black and Iranian descent.

The heavy weight of 9/11

There are other reasons war skeptics are finding more resonance today.

Above all, there’s the U.S. experience in Afghanistan and Iraq. The fact that there has been so much blood shed and money spent in those countries, with only patchy progress to show for it, weighs heavy on Americans’ minds.

Surveys by the Pew Research Center in 2019 found that majorities of U.S. military veterans as well as the general public had come to believe that the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were not worth the fight.

The untrue assertions that Iraq’s dictator possessed weapons of mass destruction, as well as new revelations that U.S. officials misled the public about Afghanistan, have further raised skepticism among Americans about going to war.

There’s also the fact that, unlike in 2001, there’s been no direct attack on the U.S. homeland.

The Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, which killed nearly 3,000 people, prompted widespread support for the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, the base for the attack’s al Qaeda masterminds. The attacks also made it harder for anti-war activists at the time, many of whom had engaged in similar activism during the Vietnam War, to gain mainstream traction and prevent the U.S. from invading Iraq.

The 2001 attacks also affected the political calculations of Republicans and Democrats.

Democrats were nearly all on board for the war in Afghanistan, but the fear of being called out as soft on terrorism led many to tangle themselves in knots over whether to support Bush’s push to invade Iraq.

This past week, Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden found himself struggling to explain his October 2002 Senate vote to authorize military action in the face of thundering criticism from Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders.

Even in 2004, as the situation in Iraq spiraled out of control and Democrats self-consciously nominated a decorated war hero in John Kerry, Republicans managed to use the national security argument in their favor to keep the presidency.

It wasn’t until a few years later, with U.S. troop deaths in Iraq nearing 4,000 and Afghanistan increasingly going sideways, that Democrat Barack Obama was able to successfully campaign for the White House by promising to avoid “dumb wars” and bring American forces home.

Obama, though, couldn’t deliver on all his promises.

He pulled U.S. troops out of Iraq only to send thousands back to help combat the rise of the Islamic State terrorist group. He ordered a surge in U.S. forces in Afghanistan, only to reduce their numbers with little gains to show against the Taliban. He stayed out of the fight against Bashar Assad’s regime in Syria, but helped overthrow Libyan dictator Muammar Gadhafi, largely through airstrikes.

Historian Michael Koncewicz said anti-war activists often point to Obama as an example of how politicians capitalize on their movement’s energy but, once in office, water down their positions and fail to live up to their promises.

That being said, anti-war activists are far more inclined to take electoral politics seriously today than 20 years ago, he said. Many see Sanders’ success in the Democratic presidential primary race so far as evidence that their message has resonance.

At the same time, there are growing efforts to further define what it really means to be “anti-war” and who counts as part of the movement. For instance, do libertarians, whose views are often more isolationist than many anti-war activists, fit under the umbrella?

“Trump, as a figure, is forcing a lot of people to rethink those coalitions and think about what are the boundaries of anti-war activism,” Koncewicz said.

Trump’s own history of fudging facts about matters large and small is also playing into anti-war activists’ hands. Already, the president and his team are drawing fire for conflicting claims on why they decided to kill Soleimani – raising immediate parallels to the pre-war intelligence on Iraq, which wasn’t as widely challenged, or as quickly, at the time.

Today, even some Republicans in Congress want to see more restraint in the use of U.S. military force, and they’ve joined Democrats in supporting legislative measures to restrict the president’s ability to wage war.

In one sign that the political atmosphere has changed over the past two decades, GOP Rep. Doug Collins of Georgia accused Democrats of being “in love with terrorists” in an interview with the Fox Business Network, only to apologize two days later on Twitter.

The reaction to how Trump has handled the conflict with Iran, like so much else, falls largely along partisan lines, but some polls show that even Trump’s supporters are worried about where he’s leading them.

An ABC News/Ipsos poll this month found 73 percent of Americans are somewhat or very concerned about the possibility of a full-scale war with Iran. A separate survey conducted by POLITICO/Morning Consult found around 85 percent of Republican voters backed the decision to kill Soleimani, but that 58 percent of them also believe it makes war with Iran more likely.

Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.), a leading voice in Congress arguing against war with Iran, said there’s simply more voters across the board questioning whether engaging militarily in the Middle East is worth it.

“Do I think you’re still going to have some people go on and say, ‘The Democrats are weak on terrorism, they’re rooting for Iran’?” he said. “Sure, you’re always going to have blowhards, but the resonance of that attack has lost its value.”

Quincy’s ‘long campaign’

The Quincy Institute’s founders say they want to end lethargic thinking in the Washington foreign policy establishment – especially the type of thinking that reflexively prioritizes military force, derides engagement with adversaries and assumes the U.S. always has a role to play.

Obama adviser Ben Rhodes has labeled such group-think as the “blob.” “There’s this reflex in Washington foreign policy circles often to say ‘There’s a problem, we have to solve it, and the way to solve it is using our military, especially in the Middle East,’” he told CBS News. “I saw that we weren’t learning lessons from Afghanistan and Iraq. We were at risk of just repeating the same mistake over and over again.”

Quincy calls itself “trans-partisan,” meaning it’s not wedded to a political party and that it taps expertise from across the political spectrum. That its funders include both Soros and Koch is just one sign of its unusual nature. Both men gave Quincy money through their foundations; Koch gave $485,000, while Soros gave $525,000. The institute’s other major funders include the Rockefeller Brothers Fund and the Ploughshares Fund.

The institute also avoids labels like “isolationism,” “pacifism” and “anti-war.” Instead, its founders say they want smarter U.S. engagement overseas, one that is less militaristic and much more invested in diplomacy – “realism and restraint,” as one associate put it.

“We have not had a healthy marketplace of ideas in the foreign policy space,” said Will Ruger, vice president for research and policy at the Charles Koch Institute. “There should be no opprobrium given to people’s desire to find a diplomatic arrangement to avoid or end conflict.”

One of the institute’s main programs is labeled “Ending Endless War.” Others focus on the Middle East, East Asia, and “Democratizing Foreign Policy.” The latter appears to revolve around the notion that “experts” – not all of whom are genuine academic scholars – should pay more attention to activists, ordinary Americans and marginalized voices.

Quincy, whose physical headquarters are in D.C.’s Foggy Bottom neighborhood, also is promoting its own online publication, “Responsible Statecraft.” The platform features opinion, analysis and reported pieces that often challenge mainstream foreign policy thinking.

One recent piece described how much more quickly the Iranian state has moved in recent years to snuff out popular protests. “Iran 2019 is not the Soviet Union in 1989, nor Libya 2011. The nature of [Islamic Republic of Iran] rule, an ideological state lacking a singular ‘Dear Leader’ in the manner of a Saddam, Qaddafi, or Assad, makes it a poor candidate for the type of rapid collapse associated with so-called sultanistic regimes,” academic Shervin Malekzadeh warned.

The institute has 14 staffers and more than 40 non-resident scholars, many of whom, by design, are based outside Washington and its think tank bubble.

Some of its staffers and affiliates are lightning rods due to their past commentary, including executive vice president Trita Parsi, an Iran specialist who has supported engaging the regime in Tehran, and John Mearsheimer, co-author of the explosive 2007 book “The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy.”

The Quincy Institute has drawn a slew of attacks, some of them pre-dating its launch.

Bill Kristol, the neo-conservative commentator who supported the Iraq invasion but is a Trump critic, accused the institute of wanting to “go back to the 1920’s and 30’s!” – implying it was isolationist.

Republican Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas, who has pushed Trump to take a hard line on Iran, more recently labeled Quincy anti-Semitic in a floor speech; the institute decried his claim as “blatantly false.”

Quincy’s founders say they are realistic about what they can achieve given how new they are and the forces they are up against in Washington. They add that although the institute has a set of core principles, it’s not demanding uniform thinking from its staffers and fellows.

“Not for a second do I believe that a handful of interviews or op-eds or essays in Foreign Affairs in and of itself is going to make a difference,” said Andrew Bacevich, a historian and retired Army colonel who serves as Quincy’s president.

It’s “a long campaign to change the way people in Washington think about America’s role in the world.”

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream