Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, started the trend earlier this week, trying to discourage what he called “reckless” travel by sending the National Guard to Florida airports to tell inbound passengers from New York and New Jersey that they needed to self-isolate for 14 days. DeSantis announced Friday that he was stepping up the effort, setting up state police checkpoints on various highways to give similar instructions to people driving in from New Orleans.

The new salvos from governors come less than two weeks after DeSantis publicly called on Trump to limit travel to his state from the most infected parts of the U.S.

Trump confirmed that he had spoken to DeSantis, a close political ally, about the issue.

“We’re working with the states, and we’re considering other restrictions,” Trump told reporters the same day.

However, no domestic travel limits have been forthcoming from the White House, even as Trump continues to boast that his decisions to limit travel from China and Europe dramatically retarded the spread of the virus in the U.S.

On Friday, Trump was evasive when asked about the issue during a White House briefing.

“We’re being very strong on quarantine,” Trump said, despite the federal government issuing only guidelines regarding domestic travel. “We’re being very strong on people not leaving certain states and going to other states.”

“Can we go to a tougher level?” Trump said later. “We can, but that causes other problems.”

If anything, Trump seems to have moved in the other direction, signaling that he wants to see lockdown-type measures lifted soon in as much of the country as possible in order to mitigate the economic damage the nation is facing.

As a result, governors are stepping into the breach, creating a hodgepodge of travel restrictions aimed at stemming the spread of the virus into their states.

Raimondo, the Rhode Island governor, used blunt language to defend her move.

“There’s no other choice. I have to make decisions that I believe are in the best interest of keeping Rhode Islanders alive,” she said.

“We’re not shutting down our border per se,” she added. “What we’re saying is: If you want to seek refuge in Rhode Island, you must be in quarantine for 14 days, and we, the people of Rhode Island, plan to enforce that.”

Gov. Greg Abbott (R-Texas) was similarly direct, saying he was trying to keep the increasingly painful scenes in New York from playing out in his state.

“We don’t want to be in a situation like New York is in right now,” Abbott said. “The New York tri-state area is the center of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States.”

Awkwardly for the White House, Abbott repeatedly stated that his decision to impose a “mandatory self-quarantine” on visitors from the New York area was based on conversations with the two most prominent federal medical officials who advise Trump on the pandemic and often flank him at his daily news conferences: Drs. Anthony Fauci and Deborah Birx.

In fact, Abbott said he added people flying in from New Orleans to the quarantine list after Birx specifically suggested it to him on the phone. “Dr. Birx mentioned it would also be helpful,” he said.

At the White House briefing Friday, Birx said her advice had been for New Yorkers “to voluntarily self-isolate and take care of themselves.”

Abbott said noncompliance would be a criminal offense punishable by a fine of up to $1,000 and up to 180 days in jail. Raimondo also threatened fines or arrest for breaking her quarantine order.

However, the Texas order covers only air travel and not road travel — a puzzling omission, especially regarding travelers from New Orleans, who are just a four-hour drive from the Texas state line.

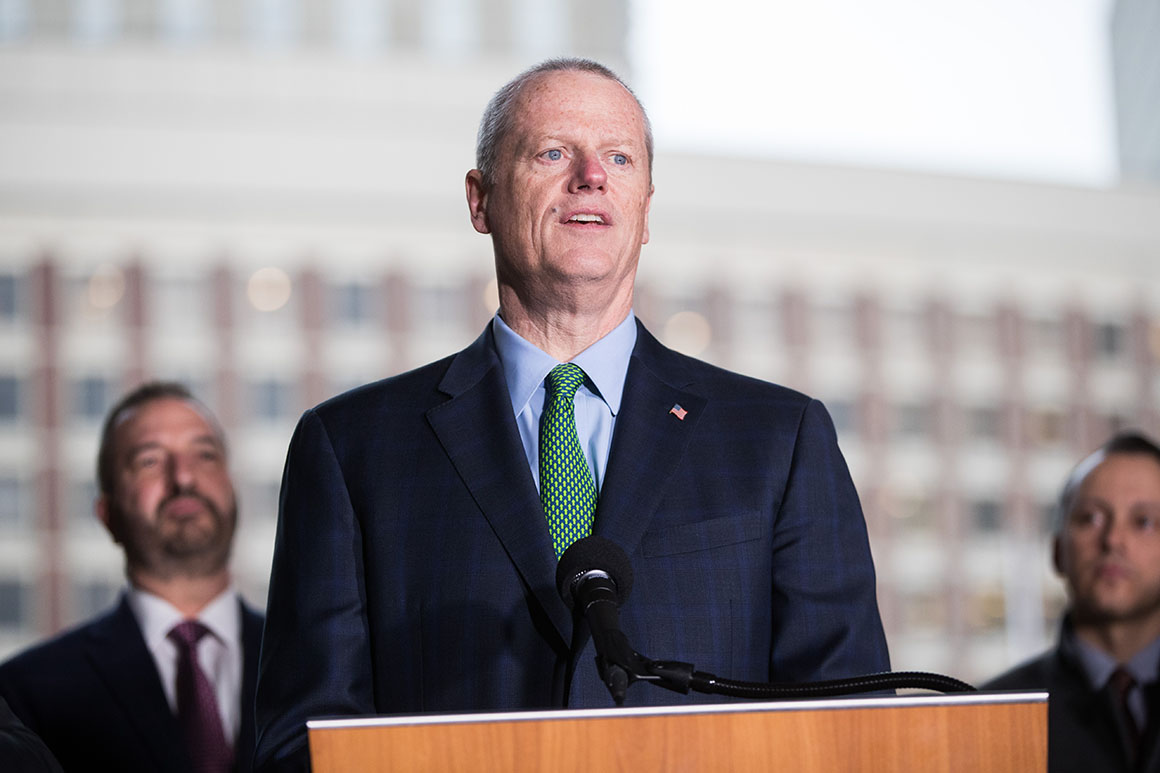

While Raimondo said she accepted that her state could be a place of refuge for some fearful New Yorkers, Baker, the Massachusetts governor, sent a blunter message: Stay away.

“Do not travel to our communities, especially if you have symptoms,” he told reporters at a news conference in Boston Friday morning.

Baker’s travel-related directive may be the broadest of its kind from any governor thus far: urging all visitors from anywhere to self-quarantine for 14 days. However, he acknowledged to reporters that there’s no real muscle behind it.

“I would call it at this point: instruction and an advisory,” he said. “There is no enforcement mechanism.”

Indeed, none of the state measures seem as effective as a federal quarantine order might be. Legal experts say Trump could bar travel into other states from virus hot spots like New York City or New Orleans.

Asked about potentially taking incoming travelers’ temperature, Baker suggested one reason he wasn’t going further was concern about bumping up against federal powers to control interstate transport.

“We are engaged in discussions with a lot of people about what we can and cannot do, OK?” he said.

There was no immediate pushback from the White House against the latest moves. However, Raimondo’s decision to stop cars with New York license plates drew fire from the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

“While the governor may have the power to suspend some state laws and regulations to address this medical emergency, she cannot suspend the Constitution,” Steven Brown, head of the ACLU’s Rhode Island division, said in a statement. “Under the Fourth Amendment, having a New York state license plate simply does not, and cannot, constitute ‘probable cause’ to allow police to stop a car and interrogate the driver, no matter how laudable the goal of the stop may be.”

Brown derided the enforcement mechanism as a “blunderbuss approach that cannot be justified in light of its substantial impact on civil liberties.”

Asked about the criticism of her order, Raimondo seemed to be braced for a legal fight, but also pointed back at officials in Washington to justify it.

“It’s consistent with all the guidance we’re getting from the federal government,” she said. “I have lawyers on my side advising me as well. … This is an emergency, and what is constitutional in one scenario is different than in another.”

Legal experts said the governors are operating in a legal gray area. All-out bans on interstate travel are likely unconstitutional, but demanding that travelers quarantine themselves because of a bona fide emergency might pass muster if challenged in court.

“Any state actions burdening [the right to travel] are subject to strict scrutiny — which means there has to be a compelling state interest,” said Elizabeth Goitein of the Brennan Center at New York University. And the limits, she added, must be “the least restrictive means available.”

In this case, Goitein said, “I think courts are going to be very deferential to the states’ interest here, but you never know.”

John Yoo, who served as a top Justice Department official during President George W. Bush’s administration, said governors may be able to draw on a little-noticed passage of the Constitution that can be read to authorize states to inspect goods, and perhaps people, crossing state lines.

The provision bars states from imposing duties or taxes on such movements “except what may be absolutely necessary for executing it’s [sic] inspection laws.”

Indeed, several states, including California, Arizona, Florida and Hawaii, have checkpoints to conduct inspections of agricultural products moving across state lines to prevent the transfer of pests.

“From that, we’ve always understood that the Constitution does not explicitly intrude into the state’s police power to impose inspection laws, such as those necessary for health and safety,” said Yoo, now a University of California at Berkeley law professor.

Passenger cars aren’t typically stopped at such agriculture checkpoints, but preventing the spread of human disease could be seen as a similar, if not more urgent, imperative.

Yoo said the evident health crisis would make it tough for a private company or individual to prevail in any legal challenge. “That would be hard to win here, since everyone can see the harm that can arise from people traveling from states where the virus is spreading quickly,” he said.

However, because of the federal government’s power over interstate commerce, Trump could potentially preempt state-imposed restrictions if he wanted. So far, there’s been no sign he intends to get that aggressive.

Most of the most federal regulations on quarantines seem to contemplate situations where a state is refusing to take measures the federal government deems necessary, not a scenario where the president thinks state governments are going too far.

It’s a question that could also arise in the coming days if Trump encourages businesses to reopen, despite state and local orders to stay shuttered in an attempt to limit the coronavirus outbreak. Legal experts of various stripes said Trump simply doesn’t have the authority to override state and local officials on such matters.

“The president does not have any tools or power to force businesses to reopen,” said Cully Stimson, of the conservative Heritage Foundation. “He cannot command governors to lift their state-based quarantines or stay-at-home orders. He can provide them data, urge them to do so, publicly call for them to do so, and the like. He has the power to hold back on some funds if they don’t lift those orders, arguably, but that would be legally and politically unwise.”

Despite the tensions between the assertive stance many states are now taking regarding travel and the Trump administration’s more laissez-faire approach, none of the governors who announced new restrictions seemed interested in tangling with Trump over the issue.

In fact, DeSantis praised the administration’s voluntary guidelines sent to states.

Baker, a Republican, did offer one view directly at odds with Trump, flatly dismissing the president’s public aspiration that the country get back to business by Easter.

“We’re not going to be up and running by Easter,” Baker said.

Adam Cancryn and Arek Sarkissian contributed to this report.

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream