Yet the administration’s reliance on its projections has nevertheless frustrated much of the public health community, which cautions that IHME has not hewed to traditional disease modeling procedures or incorporated crucial variables. The result is a rosier picture of the crisis than the one portrayed by much of the rest of the modeling world.

“The IHME model is an odd duck in the pool of mathematical models,” said Gregg Gonsalves, an epidemiologist at the Yale School of Medicine. “I fear the White House is looking for data that tells them a story they want to hear, and so they look to the model with the lowest projection of death.”

At the center of those concerns is a key element, the IHME model’s critics say. The projection makes no attempt to account for the virus’ defining characteristics, such as how easily it spreads or how long someone can be infected before they show symptoms.

Instead, it relies on data from cities already hit by the coronavirus, including in Italy and China, and matches the U.S. to a similar curve. The result is a projection that’s easily digestible and more precise in its predictions than most infectious disease models, but far more volatile as the situation plays out on the ground.

The IHME has made frequent revisions to its model over the past month. Since April 9, for example, its forecast of the nation’s death toll had risen from around 61,000 to closer to 70,000, before adjusting back down to roughly 67,000 people.

Each of its projections also includes an upper and a lower boundary, mapped out by a shaded area, which range from as few as 48,000 — a figure the U.S. has already surpassed — to as many as 123,000 deaths.

“It’s a statistical model fitting the curves of epidemics in China and other places to what they think might happen in the U.S.,” Gonsalves said, “and then constantly refitting based on new data.”

IHME Director Christopher Murray defended his team’s work as rigorous and among the best models available, arguing that the forecast simply seeks to achieve different goals than more traditional projections. The model was originally meant to help hospitals predict their supply needs, as providers across the world braced for a wave of coronavirus patients.

“We’re willing to make a forecast. Most academics want to hedge their bets and not be found to ever be wrong,” Murray said. “That’s not useful for a planner — you can’t go to a hospital and say you might need 1,000 ventilators, or you might need 5,000.”

He added that IHME’s model is far more optimistic than others in large part because it heavily accounted for the impact of social distancing — a decision Murray credited for helping pinpoint the pandemic’s national peak even as others warned of continued massive growth in cases.

“We’re orders of magnitude more optimistic. On the other hand we also called the peak correctly,” he said. “We believe in fitting models to data, and not making an assumption and then saying how my assumption would play out in a hypothetical world.”

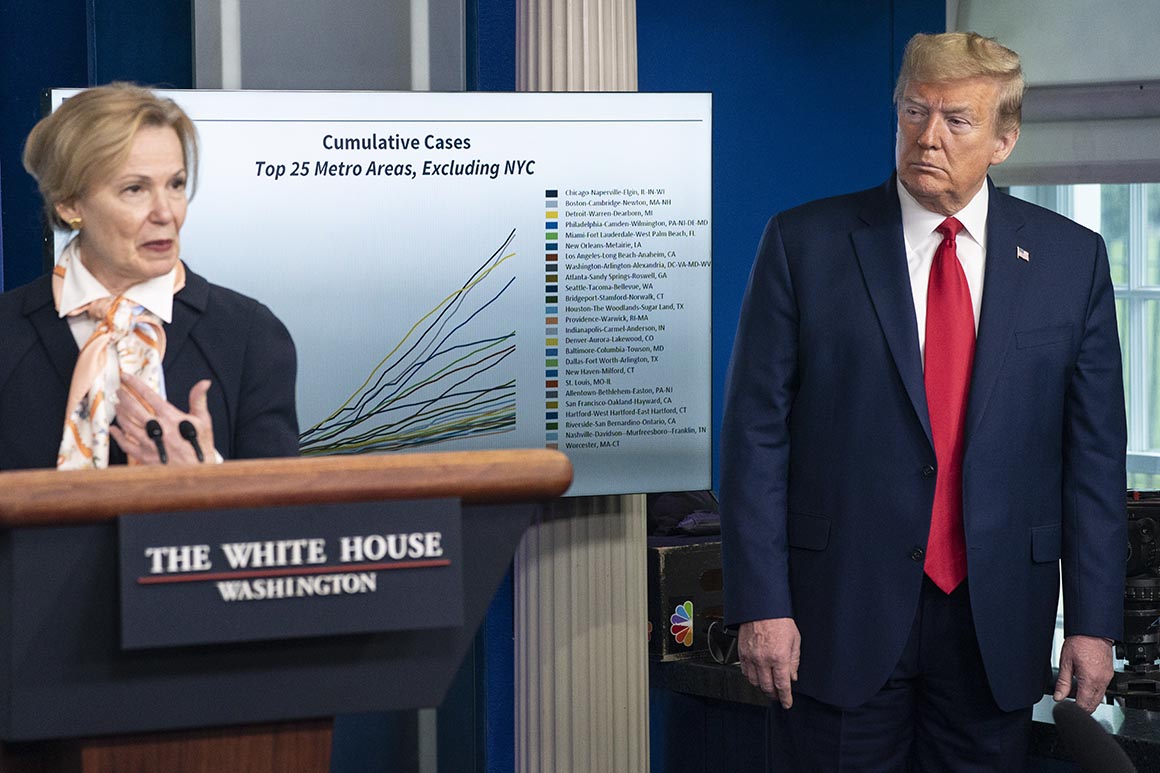

That’s caught the attention of the 2 million to 4 million people — among them numerous public-health officials and hospital administrators — who visit the site every day. It’s also won the trust of the Trump administration, which first contacted IHME in late March as it was scrambling to allocate limited supplies and head off an overwhelming of the health system, and has continued to swap data and observations with the group ever since.

As IHME grew more confident in early April that the nation’s abrupt lockdown had begun to work, so did top public health officials.

Shortly after IHME debuted its 60,000-death forecast, Fauci on April 8 echoed the sentiment, saying the administration now believed the eventual toll would be „more like like 60,000 than the 100,000 to 200,000“ deaths health officials previously estimated.

But the White House’s coronavirus task force has in recent conversations with the group focused on a new challenge: How to navigate a gradual reopening of the country, representing a new phase that will be far more difficult to model.

“That just opens up a whole new set of challenges,” Murray said, noting that Georgia — whose governor, Brian Kemp, has called for businesses to reopen far sooner than his counterparts in other states — hasn’t even hit its coronavirus peak under the IHME model.

“If Georgia’s going to have a resurgence, what about the neighboring states?” Murray said.

Compounding those concerns is what he called a “disturbing” trend of slower drop-offs in new cases in some countries like Italy, a signal that the crisis could persist for longer than expected.

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream