Watergate has long been told as a story of American exceptionalism. The system of checks and balances and public oversight worked. The Constitution triumphed over leaders who abused their power.

The word "Watergate" might be shorthand for scandal, but it’s also a story of hope: Through a combination of dogged criminal investigators, serious oversight by Congress and sustained public attention, the wheels of accountability ultimately turned even for the president of the United States.

Donald Trump and his allies are telling a different story.

In everything from casual statements and tweets to formal court filings, Trump himself — along with his staff and supporters — has been framing a version of events that feels not just unfamiliar to many Americans, but which people who lived through it likely never thought possible.

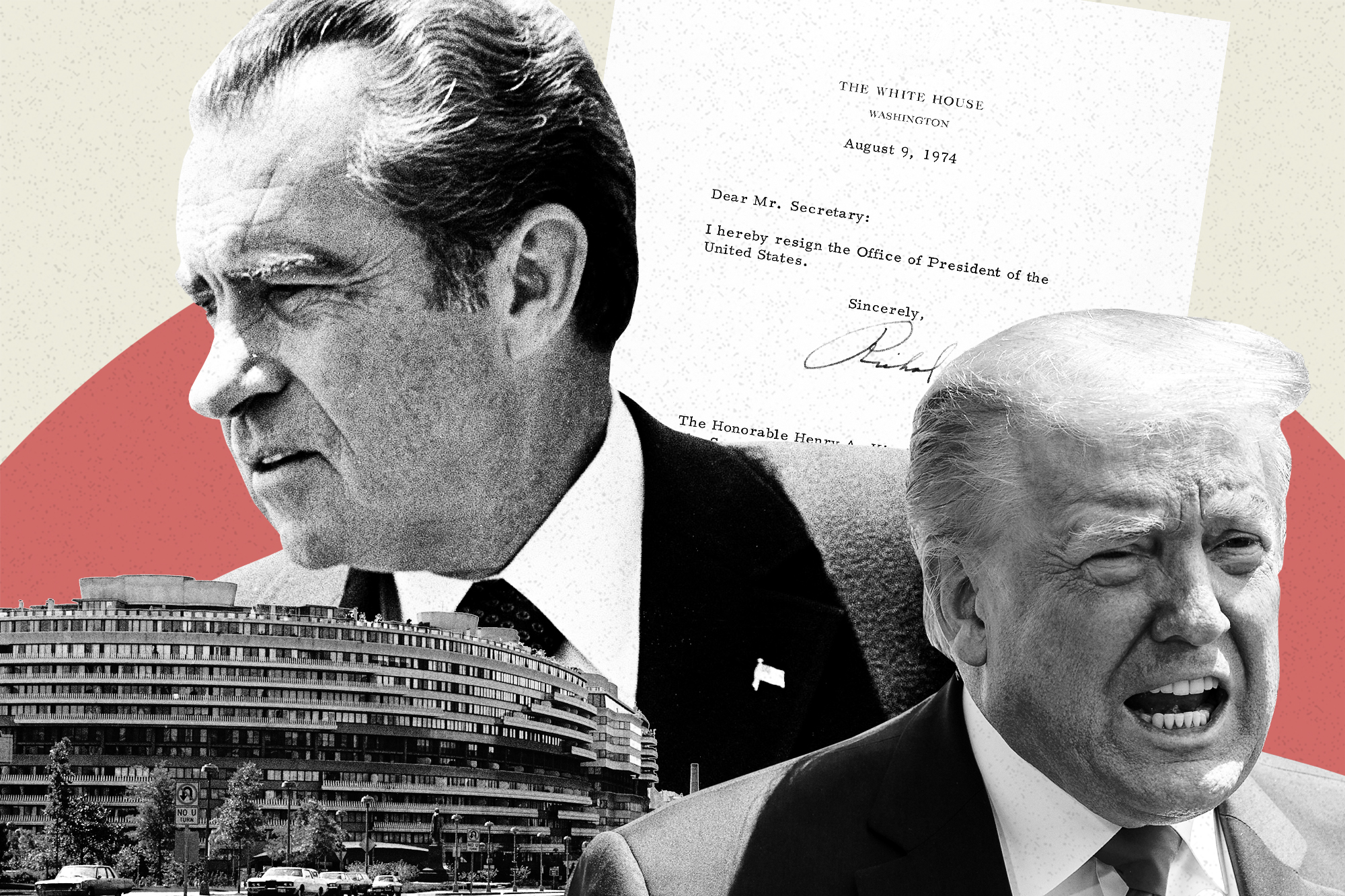

In this story, President Richard Nixon is no longer necessarily the conductor of a sprawling attempt to cover up crimes, stamp out investigations and bully people. Instead, it’s a question mark: “he may have been guilty,” Trump said. Nixon wasn’t forced out as he faced certain removal from office. According to Trump, “he left.” Trump has indicated Nixon’s biggest mistakes were that he “fired people” and “had tapes all over the place,” notably omitting why he wanted to fire people, or what behavior and cover-ups the tapes revealed. Then there’s the historic ruling that granted lawmakers in Congress access to a summary of the special prosecutor’s evidence on Nixon — a decision that propelled the congressional impeachment probe. In court, Trump’s attorneys argued the result would be “different” today.

Not only have Trump and his boosters reframed the Watergate story, they have effectively demoted it on the list of American political scandals. It now “pales in comparison” to a litany of modern-day offenses, real or not: Hillary Clinton’s private email server (real), Barack Obama secretly wiretapping Trump Tower (not), OBAMAGATE! (evidence-deficient claims about a government plot to take down Trump).

The narrative, for Trump, dates back to before his presidential campaign. But it became a far more central theme during and after his impeachment trial, and has carried over into the recent social unrest across the country. The narrative reveals itself in the way Trump himself discusses Nixon. And it has filtered into conservative media outlets and onto social media platforms, where Trump supporters dismiss Watergate when juxtaposed with the perceived ills of their rivals.

“One of these men is the most corrupt president in the history of the United States,” reads a meme shared by convicted Trump adviser Roger Stone — a Nixon acolyte — that shows side-by-side photos of Nixon and Obama.

“The other is Richard Nixon.”

As Trump muddles and skewers the Watergate story, he’s also openly revived Nixon’s rhetoric — once unthinkable for a U.S. president. There are echoes of Nixon’s talk of “plagues” of “crime” and “lawlessness” in Trump’s talk of “American carnage.” And it is outright repeated in Trump’s spree of all-caps Twitter proclamations of “LAW & ORDER!” and “SILENT MAJORITY!” — two terms linked to Nixon.

Those who studied and experienced Watergate first-hand see an attempt to achieve several goals. To start, there’s a blunt attempt to attach the Watergate millstone to Trump’s opponents. But there’s also a more subtle undercurrent: an attempt to cloud the collective memory of Nixon and fuzzy the debate about Trump’s own behavior. And legally, they also see an effort to restore authority to the presidency, which some conservatives argue was unnecessarily weakened after Watergate.

“What he’s trying to do, it seems, is to attack the very idea of presidential accountability, and the very idea that a president could have engaged in that kind of wrongdoing,” said Elizabeth Holtzman, who had just been elected to Congress in 1972 at the age of 31, then suddenly found herself working on Nixon’s impeachment proceedings just months later as a member of the House Judiciary Committee.

“So if it was fake news about Nixon,” she added, “then so much must be fake news about him.”

The result may be shifting cultural expectations about how a president can operate.

“He’s not only lessening Watergate, but he’s trying to pin others with what was clearly an unacceptable standard of conduct,” said John Dean, Nixon’s White House counsel-turned whistleblower whose congressional testimony helped turn the public against the president.

“His intuition tells him that he can use it first as a pejorative, and in doing so, he can make his conduct more acceptable in the process,” Dean added. “I think there’s no question that’s what his intuition is.”

The Watergate story

When people think of Watergate, they think of the break in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate complex during the 1972 election. Less clear are the litany of details that came after.

Yet it’s those details that have made the story, in the words of Matthew Dallek, "a really durable symbol of high crimes and misdemeanors."

First, it was a trickle — Nixon’s campaign had secretly paid the DNC burglars, but the president’s role was unknown. Then, it was a tsunami. Nixon’s campaign had a dirty tricks team conducting all manner of deceitful or illegal activities to damage political opponents: spying, fabricating information, stealing dirt. At the White House, Nixon’s aides tried to get the CIA to obstruct the FBI’s probe. His office tried to conceal records. The president had a campaign dedicated to finding ways to use government power — an IRS audit, for instance — to “screw” with his “political enemies.”

And on and on and on.

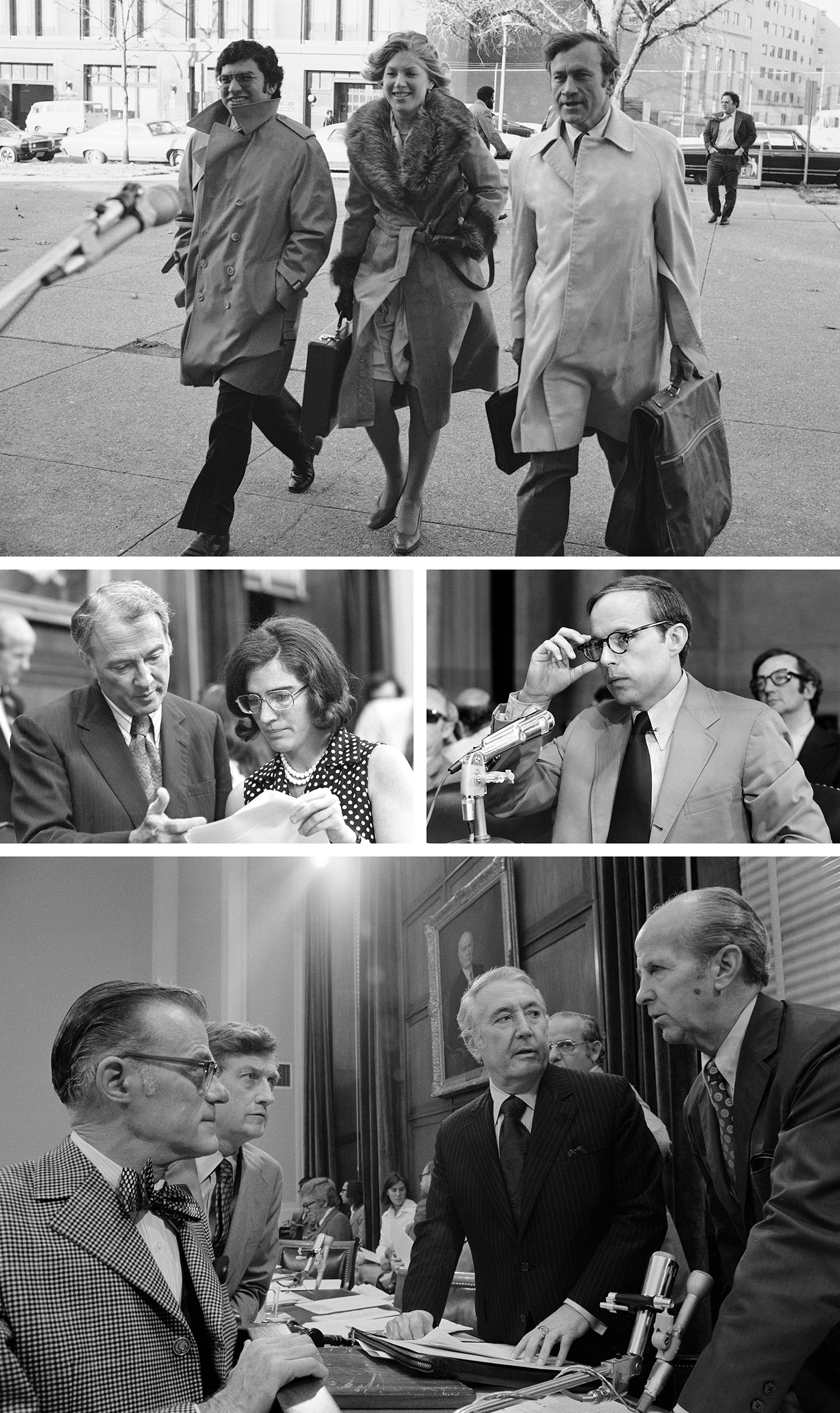

The special prosecutor’s office hired scores of prosecutors to untangle the spider’s web.

“Within our office there were five or six different teams,” each focused on a different issue, said Jill Wine-Banks, one of the Watergate prosecutors. “It isn’t just the break-in and the coverup,” she added. “The underlying crimes are more serious than a break-in that led to nothing.”

On Capitol Hill, the House Judiciary Committee also launched an expansive effort to uncover any malfeasance.

“It wasn’t a single act or a single misdeed, it was a presidency gone amok,” said Holtzman, the New York Democrat who ultimately helped write the articles of impeachment against Nixon, including one about the president’s decision to secretly bomb Cambodia during the Vietnam War. “The spectrum was huge.”

Years later, Nixon’s behavior became the standard by which all future presidential misdeeds would be judged. The government’s own researchers at the Congressional Research Service, a nonpartisan division of the Library of Congress, have written that Nixon’s “conduct exemplifies for many authorities, scholars and the general public the paradigmatic case of impeachable behavior in a President.”

Yet the event has also come to symbolize a number of American principles: co-equal branches of government, rule of law.

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous ruling, forced Nixon to hand over the tapes of his Oval Office conversations that proved the president helped orchestrate the coverup. Another judge allowed the special prosecutor’s office to give Congress a report outlining its investigation. Nixon didn’t object.

“A landmark moment in constitutional history,” said Michael Gerhardt, a historian and expert on impeachment who has testified on the issue before Congress. It was the rare moment, he said, when every arm of government — the courts, law enforcement, both chambers of Congress — “found different ways in which to hold Nixon accountable for his conduct.”

Despite Nixon’s soaring approval ratings after his landslide reelection in 1972, the public was not opposed to aggressive investigations into his behavior. Quite the opposite. Polls showed roughly three quarters of Americans agreed that appointing a special prosecutor was the right move. By mid-1973, over half of the country thought it was of “great importance.” By September, a two-thirds majority rejected Nixon’s assertion that the media was just out to get him.

Wine-Banks recalled that Jim Doyle, the special prosecutor’s press officer, decided to get the Watergate prosecutors out in front of the media based on the notion that “if we wanted to be trusted, America had to know us as people.”

“At the time, I felt we were well received,” said Wine-Banks, who recently published a memoir about her experiences, “The Watergate Girl.” “People would walk up to me and say, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re from Watergate!’”

Even Dean, loathed by some for his decision to testify against his boss, didn’t remember any open vitriol. “I’ve never had a negative experience in my life,” he said. “And that’s to my surprise.”

“There are Nixon apologists who have written revisionist histories that are just bogus, totally baloney,” he added, his voice rising. “But those people don’t have the guts to come up to me and say anything.”

So, at least from the perspective of historians and those involved in exposing Watergate, that’s the story. And Gallup polling shows opinions about Watergate’s severity didn’t waver much through the 30th anniversary of the break in — the last time the research firm examined the issue.

But narratives shift over time. The moment recedes. Fewer people lived through it. Textbooks are vague. Complex storylines are forgotten. Certain phrases enter the collective memory — “What did he know and when did he know it?” — but their substantive meaning erodes.

Those in power can more easily fill the knowledge vacuum with their own interpretation.

And, Gerhardt said, “the story of Watergate has begun to get told differently by the current people in power.”

Trump’s Watergate story

Donald Trump’s affinity for using Watergate as a rhetorical reference point spans back to his campaign days.

It appears to have started with one of Trump’s foundational campaign talking points — Hillary Clinton’s private email server. From the early months of his run for the White House, Trump capitalized on the uproar over the former secretary of State’s decision to conduct business on a personal email account, routed through a personal server located in her own house. It was a tenet of the “Crooked Hillary” nickname. And, according to Trump, the choice was “worse than Watergate.” Later, he revised it upward: “Magnitudes worse than Watergate.”

Yet while Trump used Watergate to brand his 2016 opponent as corrupt, he simultaneously revealed a natural rapport with Nixon’s style, openly embracing the ex-president’s divisive law-and-order 1968 campaign rhetoric.

“I think what Nixon understood is that when the world is falling apart, people want a strong leader whose highest priority is protecting America first,” Trump told The New York Times in July 2016. “The ’60s were bad, really bad. And it’s really bad now. Americans feel like it’s chaos again.”

On the first day of the Republican National Convention, Trump’s then-campaign chairman, Paul Manafort, volunteered that Trump would be basing his nomination acceptance speech on Nixon’s own 1968 convention speech.

“If you go back and read,” Manafort told reporters at a Bloomberg News breakfast, “that speech is pretty much on line with a lot of the issues that are going on today.”

Trump instinctually repurposes Nixon’s buzzwords, punching them out on Twitter and weaving them into Rose Garden addresses.

The tendency has surged to the fore in his response to the nationwide protests that erupted after George Floyd’s killing at the hands of Minneapolis police. Trump has favored terms like “lawlessness” that Nixon vividly used in his 1968 speech. He has warned that “without law, there is anarchy,” echoing Nixon’s lament about a “frightening trend of crime and anarchy” and his vow to “restore order and respect for law.”

“In a crude way, Trump is trying to go to Nixon’s playbook,” Dallek said of Trump’s recent remarks.

Like Nixon, Dallek said, Trump is using the protests “as a club” in his rhetorical appeal. He’s addressing “peace-loving citizens in our poorest communities” while demonizing protesters as “terrorists” the same way Nixon appealed to “the non-shouters, the non-demonstrators” and mourned “the tumult and the shouting.”

And like Trump, Nixon brought in military police to help disperse thousands of protesters in Washington, D.C.

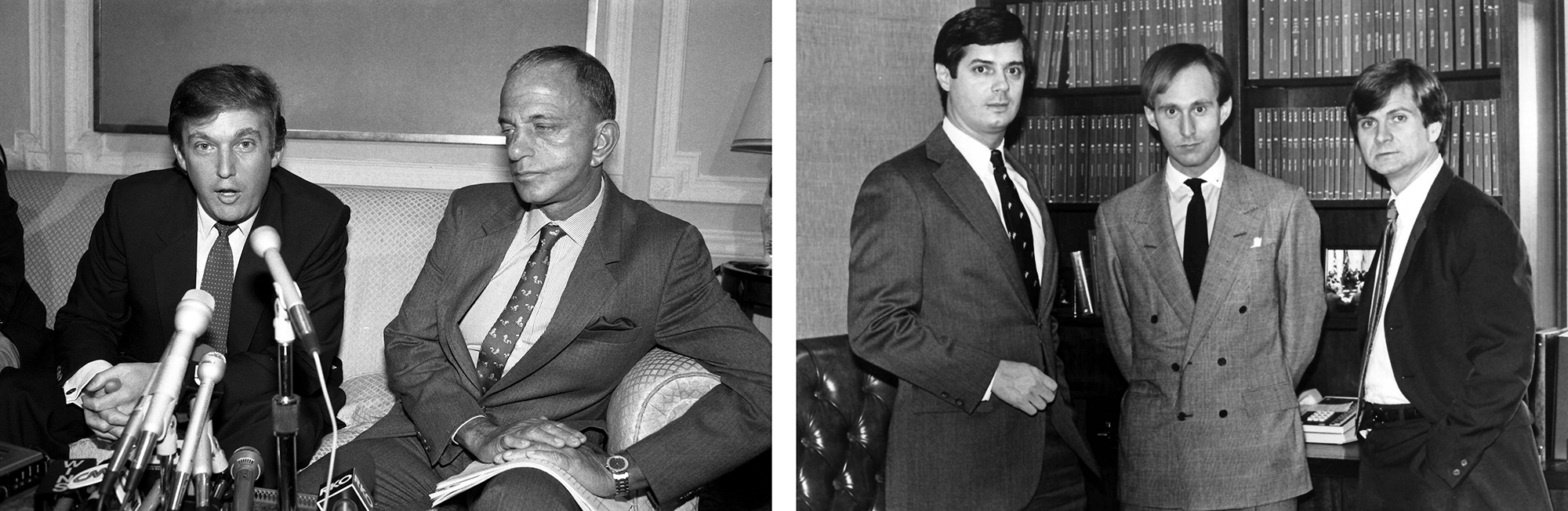

For Trump, Nixon’s allure is not an academic exercise. He actually knew the ex-president.

In the 1980s, the rising New York celebrity real estate developer moved in Nixon’s social circles. Trump was a disciple of Roy Cohn, the pugnacious lawyer and informal Nixon adviser whose punch-back tactics are elemental to Trump’s brand. Trump also befriended former Texas Gov. John B. Connally, a close Nixon friend who had been his Treasury secretary. The friendship with Connally brought Trump and Nixon together for a weekend in 1989. The former and future presidents dined together, sang “Happy Birthday” to Connally and shared a plane ride back to New York on Trump’s private jet.

Then there’s the letter Nixon wrote Trump in 1987. Nixon relayed that his wife, Pat, had caught Trump on TV and predicted “whenever you decide to run for office you will be a winner!”

“Just amazing,” Trump said, recalling the letter days after pulling off his historic election upset.

“I would not be surprised,” said John Farrell, whose 2018 biography of Nixon was a Pulitzer Prize finalist, if Trump “still has a fondness in his heart for Nixon.”

Trump’s dual-track approach to Nixon and Watergate — speaking generously about the man while excoriating opponents for behaving like him — carried over into his presidency.

He continued to attach the “worse than Watergate” tag to any number of alleged conspiracies. Evidence-free claims that Barack Obama bugged Trump’s phones? “This is Nixon/Watergate.” Accusations without proof that Obama helped entrap Trump’s national security adviser Michael Flynn? “Makes Watergate look small time!”

Together, the Flynn saga and other diffuse Obama allegations, often offered with little or no reasoning, even earned their own “gate” suffix — “Obamagate,” a word Trump regularly tweets in all-caps with no explanation.

The Onion perhaps captured it best.

“‘Just Know It’s Far Worse Than Whatever President Water Did,’ Says Trump Explaining Obamagate.”

Of course, the Trump presidency has become a “worse than Watergate” mud fight. For every hyperbolic Watergate comparison Trump makes, his opponents have been just as swift to tag Trump’s behavior as befitting of Watergate — firing FBI Director James Comey, trying to impound Robert Mueller’s probe, urging Ukraine to investigate Joe Biden.

In fact, it’s a decades-old tactic. Dean even authored a book during the George W. Bush presidency titled, “Worse Than Watergate.”

“I wish now I hadn’t,” he said, chuckling, even as he stood by his decade-old assessment.

But the dueling Watergate accusations have become turbocharged in Trump’s America. On TV, anyone with a role in Watergate was suddenly an in-demand cable news pundit. Dean linked up with CNN. Jill Wine-Banks ended up on MSNBC. Think pieces comparing Trump and Nixon proliferated to the point of cliché.

The sudden renewed interest has also brought a cultural reassessment of the Watergate prosecutors. Once seen as mostly apolitical fact finders, the lawyers who probed Nixon are now smeared by the president’s backers as Democratic Party apparatchiks.

The shifting attitudes were apparent in the fallout from the Justice Department’s recent move to dismiss its case against Flynn, who pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI about his conversations with the top Russian diplomat. Sixteen of the Watergate prosecutors, including Wine-Banks, filed a brief to the judge opposing the move.

The filing received moderate coverage across the media landscape, but it was the top headline splashed on the Fox News website: “Watergate prosecutors who want to weigh in on Flynn case include Dem donors, outspoken Trump critics.”

For each person, the piece surfaced disparaging tweets about Trump and detailed contributions to Democratic candidates. Wine-Banks was impugned for her “active Twitter presence, which is sharply critical of Trump,” and for her donations to Democratic presidential candidates Joe Biden and Amy Klobuchar. And, of course, any affiliation with CNN or MSNBC was listed as a damning charge.

The piece was a microcosm of a broader Trump-era sentiment. For the first time in her life, Wine-Banks said, she is the target of hate-filled messages and threats of physical violence. She changed her phone number at one point to evade the vitriol.

“You’re a bitch, you’re a terrible person, I can’t respect your opinion any more,” she said, summarizing the tenor of the attacks.

The Watergate court story

While Trump and his supporters relitigate Watergate rhetorically, Trump’s attorneys have started to relitigate Watergate in court.

Trump’s tenure has resurrected numerous big-picture legal questions from Watergate: What can a president shield from Congress? What investigations can a president face? Who can the president stop from testifying?

Repeatedly during Watergate, the courts ruled against the presidency. Yes, the president has to hand over certain White House tapes (he did). Yes, lawmakers can see a “road map” of the evidence Watergate prosecutors presented to the grand jury (they did). Yes, Nixon’s aides will testify (they did).

Repeatedly during the Trump era, however, the president’s attorneys have argued the opposite — with some success. No, the president doesn’t have to hand over personal documents (he hasn’t yet). No, lawmakers don’t deserve to see grand jury evidence about the president (they haven’t yet). No, Trump’s top aides will not testify during impeachment (most didn’t).

Some cases are still winding through the courts. But Trump’s lawyers have scored some partial victories, or at least slowed down attempts to get information from Trump, using arguments that cut against the premise of Watergate-era rulings. In other instances, Democrats and Robert Mueller’s team chose not to challenge Trump’s recalcitrance in court, wary of a drawn-out legal battle.

In November, Trump’s lawyers were specifically pressed on the 1974 “road map” ruling as they argued against letting lawmakers see the evidence Mueller presented to the grand jury. They argued the 1974 case would have a “different result” if heard today, citing changes in the laws.

"Wow. OK," the judge replied.

Even though an appeals court eventually ruled that Congress should get access to the grand jury evidence, the Supreme Court later temporarily blocked the release, leaving the situation in doubt.

Later, during Trump’s impeachment proceedings, Trump’s attorneys offered rationales for Trump’s behavior that mirrored Nixon’s infamous post-presidency justification: “When the president does it, that means it is not illegal.”

On the Senate floor, Alan Dershowitz parsed the Trump behavior in question: whether the president had conditioned American financial aid and a White House meeting on Ukraine opening an investigation into his political rival, Joe Biden, ahead of the 2020 election.

“If a president does something which he believes will help him get elected in the public interest, that cannot be the kind of quid pro quo that results in impeachment,” Dershowitz said.

Dean instantly saw the parallels. “Alan Dershowitz unimpeached Richard Nixon today,” he tweeted that afternoon.

The basic stance in every Trump court battle is simple, Wine-Banks said: “I’m a king and you can’t even investigate me.”

Yet the Trump team’s arguments reflect a broader suspicion in conservative legal circles of the famous Watergate-era legal decisions. Some conservative legal scholars argue that while the rulings may have felt morally righteous at the time — Nixon shouldn’t hide incriminating tapes from the Justice Department; Congress should see damning evidence — they aren’t necessarily legally sound.

If Congress wants grand jury evidence, it can call the same witnesses and ask the same questions — not turn to the courts. Maybe the president should be able to withhold information from the agencies like the Justice Department — he’s the boss, after all.

It’s an opinion Justice Brett Kavanaugh even floated as a hypothetical during a 1999 roundtable discussion with other lawyers, when he mused about whether the Supreme Court had ruled incorrectly when it forced Nixon to hand over his tapes.

“That was a huge step with implications to this day that most people do not appreciate sufficiently,” said Kavanaugh, years before Trump would appoint him to the Supreme Court. “Maybe the tension of the time led to an erroneous decision.”

While Kavanaugh has later defended the ruling in other remarks, his thoughts hint at the conservative skepticism of Watergate precedents. The wariness is tied to a broader philosophy: the “strong unitary executive theory.” John Yoo, the former deputy assistant attorney general under President George W. Bush, is one of the nation’s top advocates for the doctrine.

Trump’s team is making a pitch for that theory, said Yoo, drawing from past presidential directives, orders and briefs: “There’s a consistency.”

Under the theory, the president should have the power to hire and fire executive branch employees at will, direct government agencies and keep discussions with his advisers private — especially in times of crisis. To make it concrete: Trump can fire Comey for any reason, withhold aid to Ukraine even if Congress has already allocated it and block lawmakers from looking at White House deliberations.

It’s a concept that fell out of favor after Watergate, when such a muscular presidency was known more derisively as “The Imperial Presidency.”

Yet the unitary executive theory has since gained adherents in the conservative legal world. Some, like Yoo, lament that Watergate weakened the president’s autonomy. Yoo is perhaps best remembered for leaning on an expansive view of executive power to create the legal basis for controversial Bush-era practices like warrantless wiretapping and “enhanced interrogation techniques.”

So Trump’s team may not be explicitly saying, “We have to restore executive power lost during Watergate.”

But that might also be the result.

Trump reflects on the Watergate story

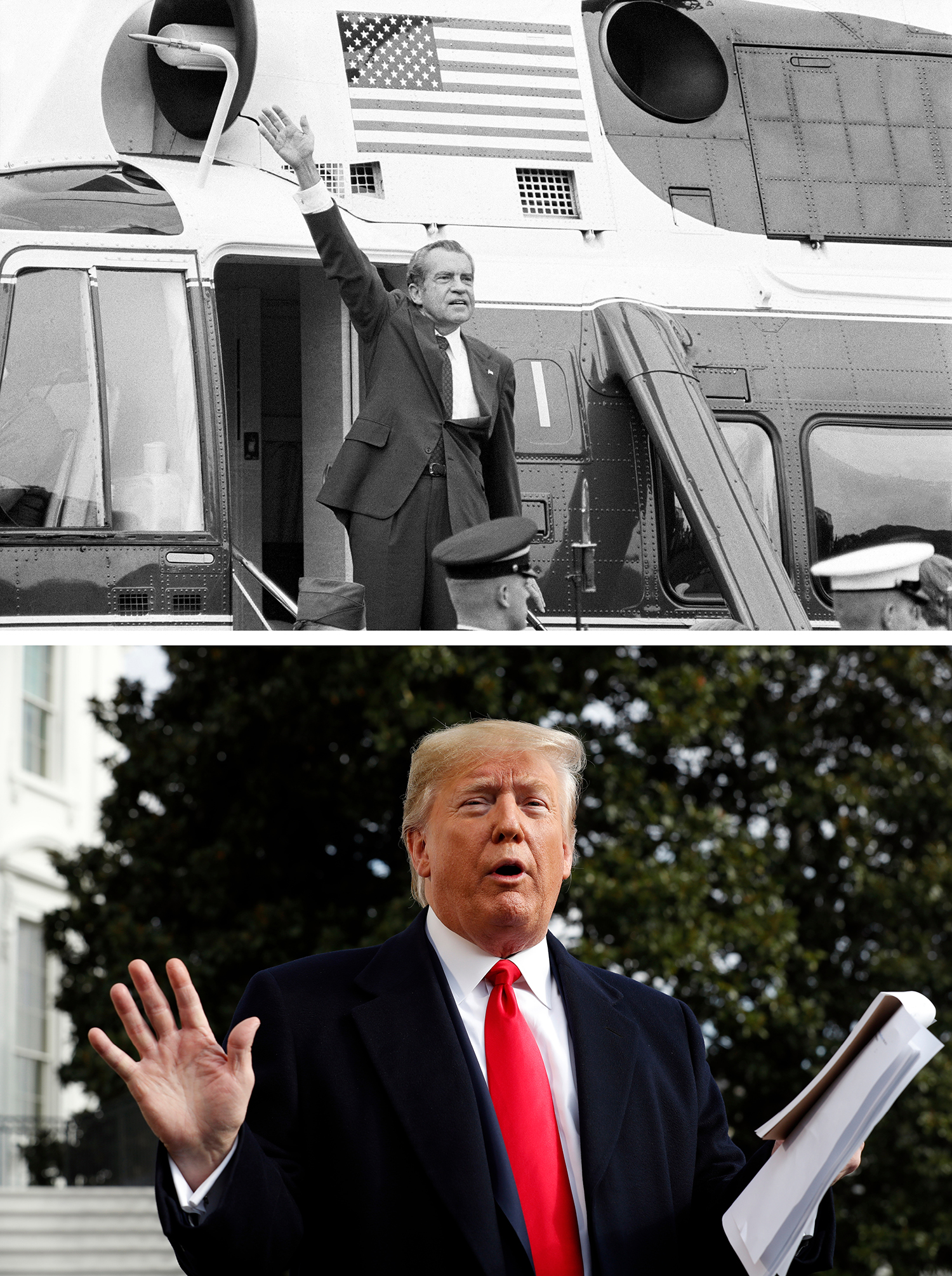

Having survived his own impeachment, Trump began to reflect on Nixon openly, without prompting.

At times, he seemed to address the 37th president as a kindred spirit for having endured a similar experience. Other times, Trump compared himself favorably to Nixon. Trump did not excuse Nixon’s behavior, but he did not directly indict the resigned president, either, hedging about the pardoned president’s culpability and alluding to the difficulties the country faced.

“I think of Nixon more than anybody else, and what that dark period was in our country,” Trump said, when asked on Geraldo Rivera’s podcast about what impeachment had been like for him.

“Every time in the White House, I pass this beautiful portrait of various presidents, right? But the portrait of Richard Nixon, I sort of — I don’t know,” he added. “It’s a little bit of a different feeling than I get from looking at the other portraits of presidents.”

A few months later, phoning into “Fox & Friends,” Trump offered one lesson learned from studying Watergate.

“Don’t fire people,” he said, a reference to Nixon’s Saturday Night Massacre, in which the top two Justice Department leaders resigned rather than carry out Nixon’s orders to fire the Watergate special prosecutor. Despite persistent rumors, Trump never fired his own special counsel, Robert Mueller, even if Mueller uncovered evidence that the president had tried to do just that.

And when he directly compares himself to Nixon, Trump highlights a few telling differences.

“No. 1, he may have been guilty, and No. 2, he had tapes all over the place,” Trump said on “Fox & Friends.” “I wasn’t guilty. I did nothing wrong, and there are no tapes.”

But the biggest differentiator? Trump fights, Nixon quit.

“He left. I don’t leave,” Trump said in early 2019. “Big difference. I don’t leave.”

The juxtaposition is striking to historians. “He compares himself to Nixon, but he does so with a guarded view of Nixon as a loser and Trump as a winner,” said Gerhardt. “Nixon gave up.”

To Trump, the Roy Cohn acolyte, giving up is anathema to his marketed personality. Can’t repay a loan? Countersue. Advisers telling you not to pull out the Iran nuclear deal? Do it anyway. Under pressure for touting hydroxychloroquine? Take it yourself.

Implicitly, however, Trump’s words also cast Nixon in a new light. Nixon is no longer a man whose corrupt behavior left him with no choice — resign or be fired. Instead, Trump frames Nixon as a man who prematurely walked off the battlefield.

“He’s trying to say, ‘Well Nixon just screwed up by getting caught,’” Dean said.

It’s an attitude, Gerhardt added, that pervades Trump’s entire team: “You can hear it in his lawyers’ arguments during the impeachment trial — and since.”

The consequence of a changing Watergate story

It’s been nearly five decades since the break-in at the Watergate that started it all.

The moment arguably seeded a shift in American culture. The short-term fall-out rattled society: a president resigned from office. The long-term fall-out reshaped America.

For years, post-Watergate cynicism instigated exhumations: How are elections financed? How do authorities spy on and investigate suspects? How does the government keep a check on its own malfeasance?

The answers, uncomfortable at times, spurred a “post-Watergate morality” era. Caps were placed on campaign contributions; limits were placed on government surveillance; transparency laws were strengthened; inspectors general were institutionalized; a new law codified how an independent counsel might investigate future presidents. Congress tried to rein in the president’s war powers and asserted its right to force the president to spend money it had approved.

“The greatest effect of Watergate was a string of reforms that gave more power to the Congress and took it away from what was seen to be a rampant executive,” said Farrell, Nixon’s biographer.

“You had this widespread feeling in the 1970s,” he added, “that really there was rot at the core of the apple.”

Elizabeth Holtzman, the New York Democrat who sat on the House Judiciary Committee during the Nixon impeachment investigation, authored a bill that formally established rules for appointing an independent counsel outside of the Justice Department.

“What we did in that legislation,” she said, “was to remove as much as we constitutionally could the attorney general from the prosecution, investigation of the president.”

Yoo and other conservatives saw a different outcome: a corruption of the traditional structure in which each branch — executive, legislative, judicial — checks the other branches. “Ambition would counteract ambition,” as Yoo said the founders intended.

In the decades since Watergate, many of the 1970s good-government statutes have been rolled back. The independent counsel statute expired in 1999. Court rulings eroded campaign financing restrictions. Surveillance soared after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Trump fired numerous inspectors general with no legal ramification. And when it came time to investigate Trump and his campaign, it was up to the attorney general to appoint a special counsel — exactly what Holtzman wanted to avoid.

“If you forget history, you pay a terrible price,” she said.

Inevitably, though, the years make Watergate’s lessons distant. The fault-lines become muddied. The story we tell ourselves is fuzzier. U.S. history textbooks are vague about the details.

“Watergate as the great right-and-wrong drama of one generation’s time I think has faded,” Farrell said.

And Trump can exploit that.

“Does our pretty primitive grasp of history allow manipulation of that history? Yes, it absolutely does,” said Michael Schudson, a Columbia Journalism School professor who wrote a 1992 book, “Watergate in American Memory.”

Trump, his lawyers and his supporters don’t even have to tell their own clear story about Watergate to have an impact. The insinuations that Nixon “may” have been guilty, or that Nixon only left office because he chose to quit, “injects this element of doubt,” said Matthew Dallek, the political historian, spurring suspicions “that there are conspiracies everywhere to take powerful people down.” That’s a narrative Trump eagerly flames when confronted with many allegations — from charges of sexual assault to criticism of his coronavirus response.

And if everything is “worse than Watergate,” Watergate becomes run-of-the-mill political intrigue, not the archetype of presidential corruption. It creates, Dallek said, “a kind of numbing effect.” A numbing effect Trump can use to normalize his own behavior, his critics argue.

“Truth doesn’t matter, what matters is the narrative,” Gerhardt said. “It’s much more important what people believe than what they know.”

A changing Watergate narrative creates opportunities. Opportunities for lawyers to challenge Watergate’s legal principles, as Trump’s lawyers have done, arguing the president doesn’t have to respond to subpoenas or submit to investigations. Opportunities for a president to morph already eroding post-Watergate norms, as Trump has done, attempting to bypass Congress on funding for a border wall, opining about DOJ cases involving his allies, authorizing the assassination of an Iranian commander without telling Congress.

And on and on and on.

The future Watergate story

Trump will not be president forever. His take on Watergate will recede.

Then what?

Those on the frontlines of Watergate insist the event has durability. Decades later, Nixon’s misdeeds are not factually in dispute, the loosening of post-Watergate oversight laws is not permanent, the famous court rulings of the era have been challenged but not completely upended.

If anything, they argue Trump’s time in office has spurred renewed interest in the kinds of anti-corruption laws that were passed after Watergate. They see a future that includes a resurgent Congress passing bills to prohibit some of Trump’s actions — punishing inspectors general, redirecting congressionally approved funds — the way a post-Watergate Congress moved to forbid some of Nixon’s behavior.

“He’s going to weaken the presidency,” Dean said, “not strengthen it.”

Yoo predicts the opposite — a continued dissolution of the Watergate anti-corruption laws. Trump’s courtroom arguments are ascendant in the legal community, he insisted, and may help return the government to a “cleaner, what I think of as a spartan view of the separation of powers.” Under this scenario, Congress and the president would once again have to settle disagreements without relying on judges or special prosecutors to step in.

Dean is in the early stages of a book about Watergate at 50. In that half century, Dean said, Watergate has “consumed my life in a way I never thought it would.” New Watergate conspiracies repeatedly pushed him to respond. New presidential behavior drew his commentary about how it compared to Watergate.

“I realize how much misinformation and how little understanding there is,” he said. “Trump has certainly created interest in it because of his behavior, his own references to it.”

Dean, Holtzman, Wine-Banks and those who study and teach Watergate are emphatic the scandal will survive in the country’s collective memory as a tentpole of presidential corruption.

“We have the tapes,” Holtzman said. “Nixon’s guilt is writ large. There’s no question about it. I mean, Trump can say what he wants, but the tapes are there.”

She added: “He can’t undo that.”

Holtzman cited an aphorism about the difficulties of permanently altering facts, commonly attributed to Abraham Lincoln: “You can fool all the people some of the time, and some of the people all the time, but you cannot fool all the people all the time.”

The problem is, though, Lincoln likely never said that. People have simply come to believe it over time.

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream