Complicating the calculus, a super PAC for Elizabeth Warren is spending in major media markets to boost her vote in congressional districts and statewide. And Mike Bloomberg, the billionaire self-funder making his primary debut, has spent more than $120 million on TV and digital ads across California and Texas.

Sanders has long viewed California as a welcoming state for him based on its demographics and politics. Ben Tulchin, Sanders’ San Francisco-based pollster, said the campaign early last year began to see his potential with Latino voters if they were able to communicate his core message of being the son of an immigrant who came to the U.S. for a better opportunity and spending much of his life trying to take on a rigged economy propped up by a corrupt political system.

“We found that economic message particularly resonated with Latinos and we saw in Nevada that play out very well,” Tulchin said.

Sanders’ considerable advantages here follow years of intense focus: He has been eyeing California’s massive delegate share — 415 pledged delegates, plus 79 superdelegates — since he lost the state to Clinton by 6 percentage points, with more than 360,000 votes separating them.

For Sanders’ supporters, there is added motivation in pushing him over the top this time. Less than 24 hours before the June 2016 primary, The Associated Press called the nomination for Clinton based on a survey of superdelegates, rendering the votes of more than 2 million Sanders backers functionally meaningless.

“Now, it’s almost like he had a bad date in 2016 and he’s back,” said Paul Mitchell, vice president of Political Data Inc. in Sacramento, who is tracking ballot returns in real time. “He’s brought the roses, he’s done his hair and brushed his teeth and now he’s ready to go. He’s been given a second chance to make an impression.”

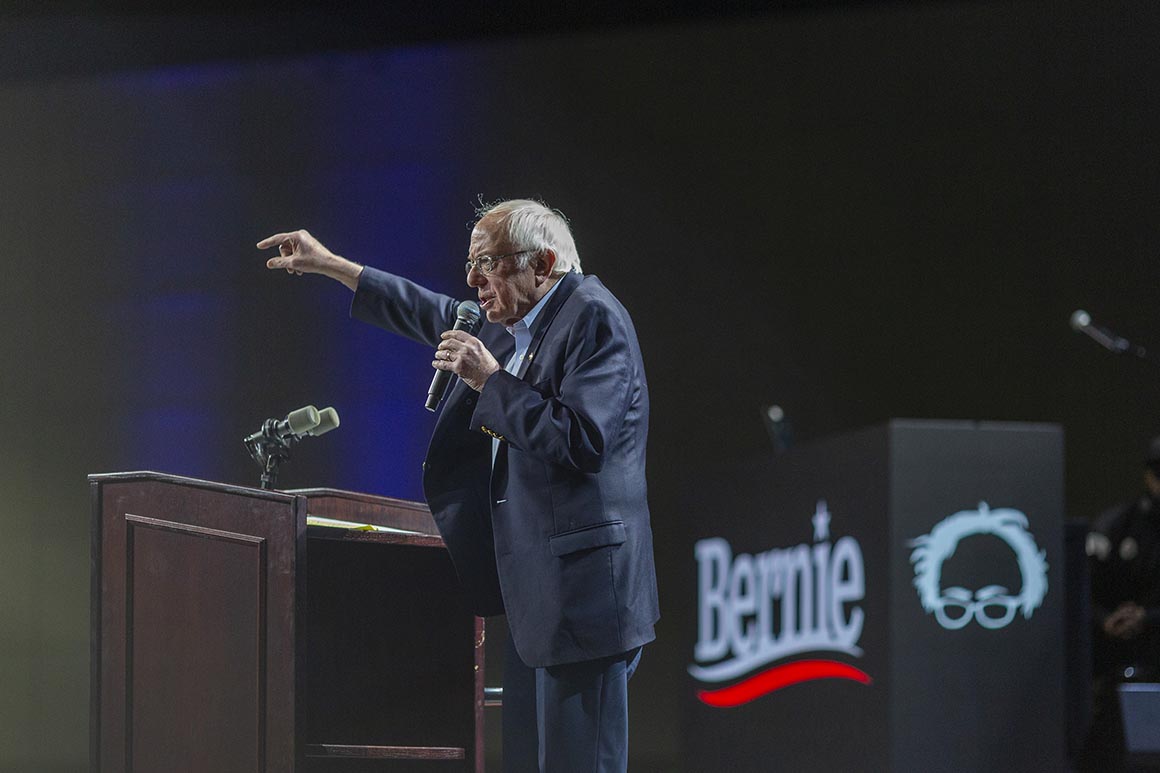

At weekend rallies in San Jose and Los Angeles, Sanders nodded to California’s importance to his campaign while aides urged the nearly 25,000 attendees to follow state election rules that allow independent voters to request — and cast — a ballot in the Democratic primary. Sanders’ campaign has spent unprecedented time and money courting independents, running digital ads, sending thousands of calls, texts and customized mailers and putting the candidate out as part of a string of news conferences to familiarize them with the rules.

„NPP & INDEPENDENTS,” one ad on Spotify reads, „REQUEST YOUR PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY BALLOT.” A mailer from the Sanders campaign spells out the specific process, step by step, to request a Democratic presidential ballot and includes the vote-by-mail ballot application itself.

Chuck Rocha, a senior Sanders adviser and architect of his Latino outreach effort, refers to the play as his “secret strategy to win California by a big number.” “There are 6 million [no-party preference] voters. Three million are going to get a ballot in the mail that does not include the presidential ballot,” Rocha explained in an interview. “And these people are overwhelmingly Latino and young. Guess who young Latinos love?”

Rocha said he targeted so-called NPP voters by calling them and literally patching them though to their county election officials to request a ballot in real time. It’s a process Rocha has used before to help put constituent pressure on members of Congress on policy issues — but never on the Sanders campaign. “We used that technology, which is something nobody has done before.”

Sanders’ campaign also spread its message to Latinos in Spanish-language TV ads. The early investments could be crucial as Biden works to consolidate moderates after their first choices dropped out.

“We were there first and we never left so we built that credibility that some late endorsement and people dropping out, they don’t affect,” Rocha said. “Because millions and millions of people were voting in California early and we were literally driving them to the polls.”

Biden’s state operation pales in comparison. Through Sunday, the former vice president had spent just over $350,000 on California ads, compared with Sanders’ nearly $7 million. Their overall Super Tuesday ad spends were $1.6 million for Biden and more than $15 million for Sanders.

„They worked very hard on the Latino vote and had a very good outreach program,” said Mark Longabaugh, a former top adviser to Sanders’ 2016 campaign who parted ways with him in early 2019. “Bernie has been working to win over Latino voters since the end of the last campaign. It was a long-term effort and looks to have paid off.”

Beyond the delegate math, Sanders’ allies here see the state as a tipping point for his campaign given what it would signify to have Democrats in the world’s sixth-largest economy line up behind his calls for large-scale, progressive change.

“California is now the Golden State for people who want to live a modern life that embraces technology, social change, environmental protection and appropriate checks on corporate power. And if we put our Good Housekeeping seal of approval on a Bernie presidency, it’s going to make it a lot easier for the rest of America,” said Jamie Court, a longtime Sanders supporter with Consumer Watchdog, which does not make endorsements for president.

“We’re not a surfboard, tie-dye culture. We’re the center of Silicon Valley, the agricultural economy and the military industrial-worker complex,” Court added. “We are actually a self-contained economy and political structure that is a perfect replica of the Democratic establishment and the independent establishment around the rest of the country.”

Sanders’ comprehensive plan took years to develop. After his 2016 loss, he returned during the midterm elections for a late October rally in Rep. Barbara Lee’s heavily Democratic East Bay Area congressional district. Over shouts of “Bernie 2020,” Sanders urged his followers to stay in the fight even in nonpresidential years and show their strength by pushing up turnout.

Before that, Sanders returned to campaign for a drug price initiative and stir support for a stalled universal health care bill in the Legislature similar to one he’s been pushing for in Washington. Those visits — along with trips tied to events for the nurses union — were unmistakable signs that he was going to do things differently than most of his rivals who spent their time raising money in Los Angeles, San Francisco and Silicon Valley.

“Bernie learned from last time,” Court said of 2016. “He did what [noted labor activist] Joe Hill said, which is, ‘Don’t mourn, organize!’”

It may take weeks to discover whether Sanders’ California gambit pays off. Late-breaking mail votes that pour into the state take considerable time to count. And experts warned that other candidates with momentum could see their numbers improve dramatically. In 2016, Sanders closed the gap with Clinton by several points after Election Day. This year, it is Sanders who’s left hoping nobody else comes on strong late.

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream