The Covid pandemic has wreaked havoc on the U.S. economy. Around 33 million unemployment claims have been made, and hunger stalks millions more Americans—and that’s aside from the ravages from the disease itself.

Yet big disruptions can bring big opportunities. Thinkers have already been considering how the world could emerge better, or smarter, from the Covid plague. And there’s real historical precedent for this: The Italian Renaissance may have begun before the 14th-century plague known as the Black Death, but there’s a strong case the disease—in both its ravages and the social changes it enabled—helped accelerate its progress, especially in the city of Florence. For a time, Florence’s economy bounced back with remarkable social mobility, and it became Europe’s premier center of artistic, cultural and scientific creativity.

Can we really hope for the coronavirus to usher in a golden age of economic mobility, creativity, learning and artistic achievement? The story of Florence was recently the topic of a sweeping article making this argument. But the example of Florence, while encouraging in some ways, also suggests there are signs we are doing it wrong. The Florentine approach to the Black Death is a helpful model as the world looks to rebuild after Covid, and if we look closely, we can see it contains some warnings for us—and some lessons we are already missing.

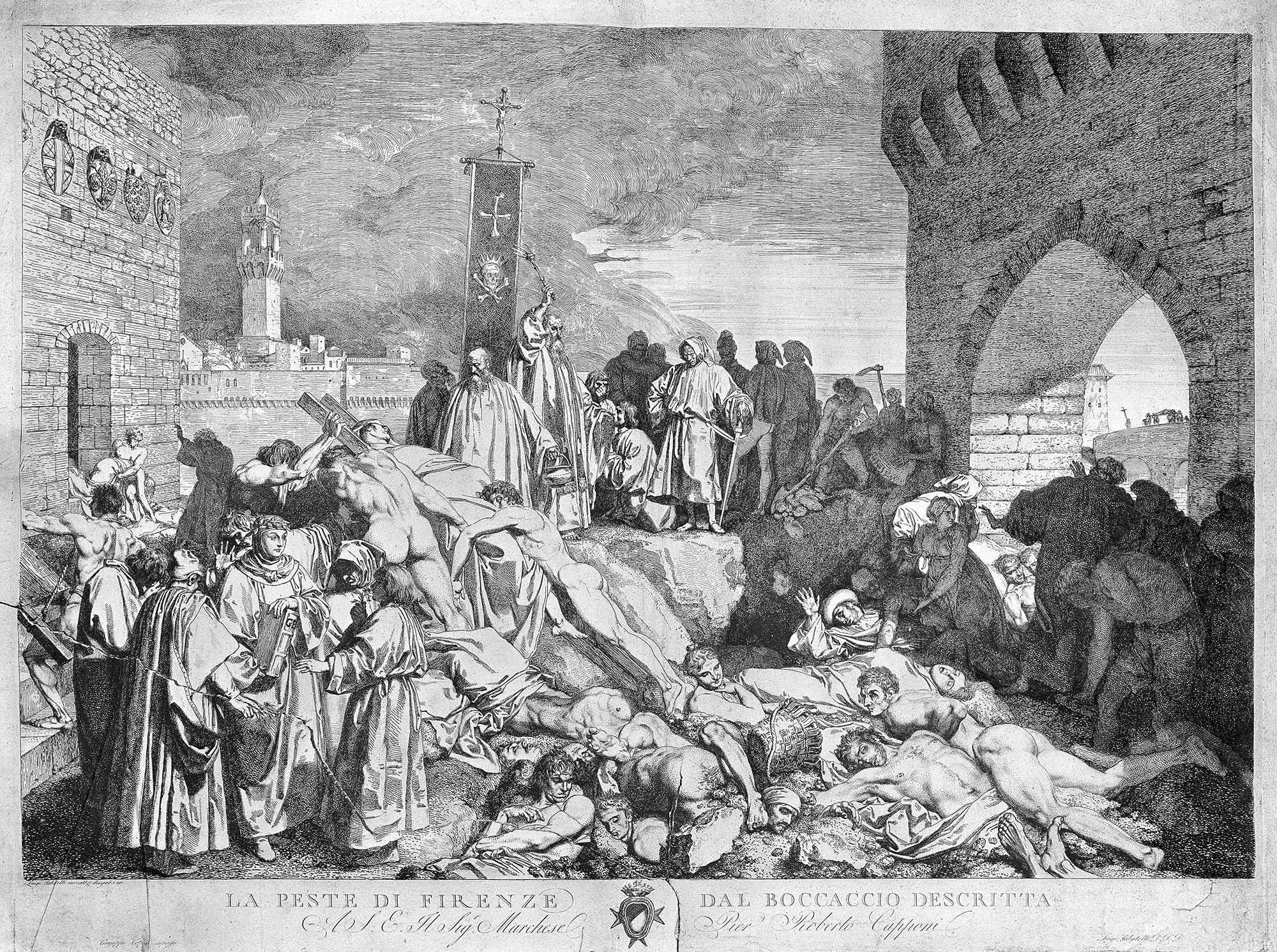

In sheer numbers, the Black Death of 1348 was an unalloyed horror. The bubonic plague killed between 30 and 70 percent of Europeans, and left the survivors bereft. At the height of the plague, in 1349, the poet Petrarch wrote: “The life we lead is a sleep; whatever we do, dreams. Only death breaks the sleep and wakes us from dreaming. I wish I could have woken before this.” His son Giovanni survived that plague only to die during a recurrence in 1361.

The Europe that emerged afterward was different and, due to depopulation, offered new opportunities. Florence may be the clearest example where the plague led to a remarkable opening of the social system as wealthy families and institutions welcomed what were called “new men” into their families and their business guilds.

It helped that Florentine society had already been laying the groundwork for change. Before the plague of 1348, Florence had begun opening the city to gente nuove, non-aristocrats who relied on business for their fortunes rather than inherited agricultural holdings or old banking money. It also enjoyed unusual literacy. Early 14th-century Florence was filled with well-educated notaries, and even artisans. It was also, even before the plague, undergoing a disruption. The period from 1339 to 1349 has been called the “decade of disaster” in Florentine history, as the great banking houses of the Bardi, Peruzzi and the Acciaiuoli went bankrupt in the years leading up to 1348, bringing down lesser firms with them. Then a far bigger disruption came: Around 60 percent of the population died in the plague, including many leading members and scions of great houses. With the business climate unstable, and labor scarce, the old patrician families had to give up their businesses and invest their wealth in more secure landholdings and bonds.

But with openings caused by mass death at all levels of Florentine society, “new men” flooded Florence. This did not necessarily sit well with the old guard. Even before the Black Death, the historian Giovanni Villani, who himself would later die from the plague in the middle of writing a passage of his Chronica, complained that the city was filling with “artisans, manual laborers and idiots,” who caused the city many “troubles.” However, after the plague, many of these “new men” began to earn spectacular fortunes, much in the way the older banking families had. And they, in turn, resented the patrician families. In 1378, this helped lead to a civil war between the Guelph party of the patricians on one side, and the new men and the poorly paid Ciompi day laborers on the other.

While the competition raged, it also forced institutions open, as new men joined the political elite and civic associations. Even old guard organizations overcame their trepidation, such as the distinguished Opera del Duomo, which supported the upstart architect Brunelleschi—resulting in the famous cupola of the Florence cathedral. Rivalries existed, but slowly alliances formed, such as between the Ricci and the Albizzi families, and the Florentine society and economy allowed extraordinary mobility.

At the levels below the elites, the plague was a boon for surviving workers, and began attracting new talent to the city. Those who survived the plague and received large inheritances had problems filling posts. Skilled labor was in short supply and wages of even unskilled workers grew in some areas. As local artisans joined the guilds of elite merchant bankers and silk-makers, outsiders came to fill their posts. Even non-Florentines were allowed to join the prestigious guilds, such as the famed “Merchant of Prato,” Francesco Datini, who made a great personal fortune in the old professions of Papal banking, wool-making, alum and arms trading.

City government allowed representation from all levels of the guilds, so that lower guildsmen—laborers and artisans—sat in government alongside the wealthy, and were given an opportunity to participate. This did not mean full representation and legal rights for all members of society, but it expanded participation in government. The legal system gave near equal consideration to lawsuits, regardless of wealth and class. Schools opened up and admitted men (education was mostly limited to them) of all classes. Florentines reached a staggering level of literacy in the late 1300s in reading and financial accounting, both crucial to the city’s rebirth. A century later, the man who took over the Florentine republic, Cosimo de’ Medici, sent his son to school side by side with a brass-maker’s boy—a juxtaposition that would have been unlikely in the Middle Ages.

It was this atmosphere of social and economic mobility, literacy and widespread participation in government that led to the Florentine Renaissance. Artisans and artists could take full part in Florentine social and economic life. Some artists, like Brunelleschi, the son of a notary, had a classical education. Many others attended abacus accounting schools, and became acquainted with the learning of classical Rome on their own, through personal enthusiasm, or on the shop room floor. In any case, they had the possibility to push for a higher social status, from lower artisan to renowned artist, and their literacy was key in achieving that. The great painter Filippo Lippi was the son of a butcher; both Lorenzo Ghiberti and Donatello were goldsmiths (Donatello trained in Ghiberti’s shop). Leonardo da Vinci was the son of an umarried notary and peasant woman, who trained to be an artist as an assistant in Verrocchio’s workshop. Leonardo taught himself Latin and geometry, which were at the basis of his staggering works and inventions. Of course, not everything had changed: It was the patronage of the rich that would give artists freedom and renown.

The Florentine lesson isn’t that a plague is good for you. No one wants thousands or millions of people to die so that others can have the opportunity to take their place.

But it shows clearly that the right systems and opportunities are crucial to benefit from a crisis. A society that in some ways had been trapped by its aristocracy and tradition then put itself in a position to capitalize when those were disrupted, through an enthusiasm for learning and art—with results that made Florence a center of invention, scholarly and artistic creation, and prosperity for centuries.

Do we have that opportunity now? Maybe. We certainly have the means and the institutions to achieve these goals.

But the signs, right now, are that America at least is heading the wrong way. As the economy crumbles, low- and middle-income workers are being laid off, while at the other end the stock market has soared and the net worth of wealthy Americans continues to grow. Small businesses are shutting down; Amazon has never been more valuable. Many privileged Americans are profiting and staying safe, while economically insecure Americans walk into risky jobs, and young people, the poor and immigrants—a natural talent pool to help build the future—are increasingly blocked from even entering the country.

Florentines managed to use their experience of the plague, partly on purpose and partly by accident, to bridge wealth gaps and create whole new kinds of opportunities and new visions of the world. Right now, it appears Covid-19 is doing the opposite, widening the inequality gap even further, letting it divide our society even more radically.

It’s possible America could still get this right. By the time the economy does open back up, it’s incumbent on us to ensure we lay the groundwork for people all the way down the ladder to seize the opportunities it might offer. And here, Florence may have another lesson: What really enabled the Renaissance was a deep dive into humane learning. People from all walks of life read about the ancient past, studying books in the hope of recreating Cicero’s ideal of a civic regeneration through education.

America has done this right (or at least partially right) before: After the disruption of the World War II, the GI bill allowed young men to study the arts and sciences so they could dream, and achieve, things their parents hadn’t been able to. It didn’t solve all of America’s inequities; the beneficiaries were mostly white, and Black GI’s benefited far less. But we can learn something from the impulse behind it. It was by mixing the humanities writ large with practical, artisanal skills—and a society ready to use them—that Florence produced Donatello and da Vinci. Ours, too, are out there, of all races and creeds. All they need is a chance.

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream