At the farthest northwest corner of Florida, straddling the border with Alabama, sits a sprawling, ramshackle beach bar called the Flora-Bama Lounge. First opened as a roadhouse in 1964, it’s celebrated in song by Jimmy Buffett, and known as much for its bushwackers (a cocktail like a chocolate piña colada that’s made with five different liquors) as for its beer pennants strung with hundreds of bras. Poet Beth Ann Fennelly once called it the one and only “five-star honky-tonk of the Redneck Riviera.”

Nothing captures the slightly trashy, sweetly laid back, anything can happen here vibe of Florida beach culture quite as neatly as the Flora-Bama’s annual Interstate Mullet Toss. Every April, some 30,000 people gather on the beach in front of the Flora-Bama to see who can toss a dead fish the furthest across the state line. They go through about 1,000 pounds of mullet and raise thousands of dollars for charities like the Boys and Girls Club.

But not this year.

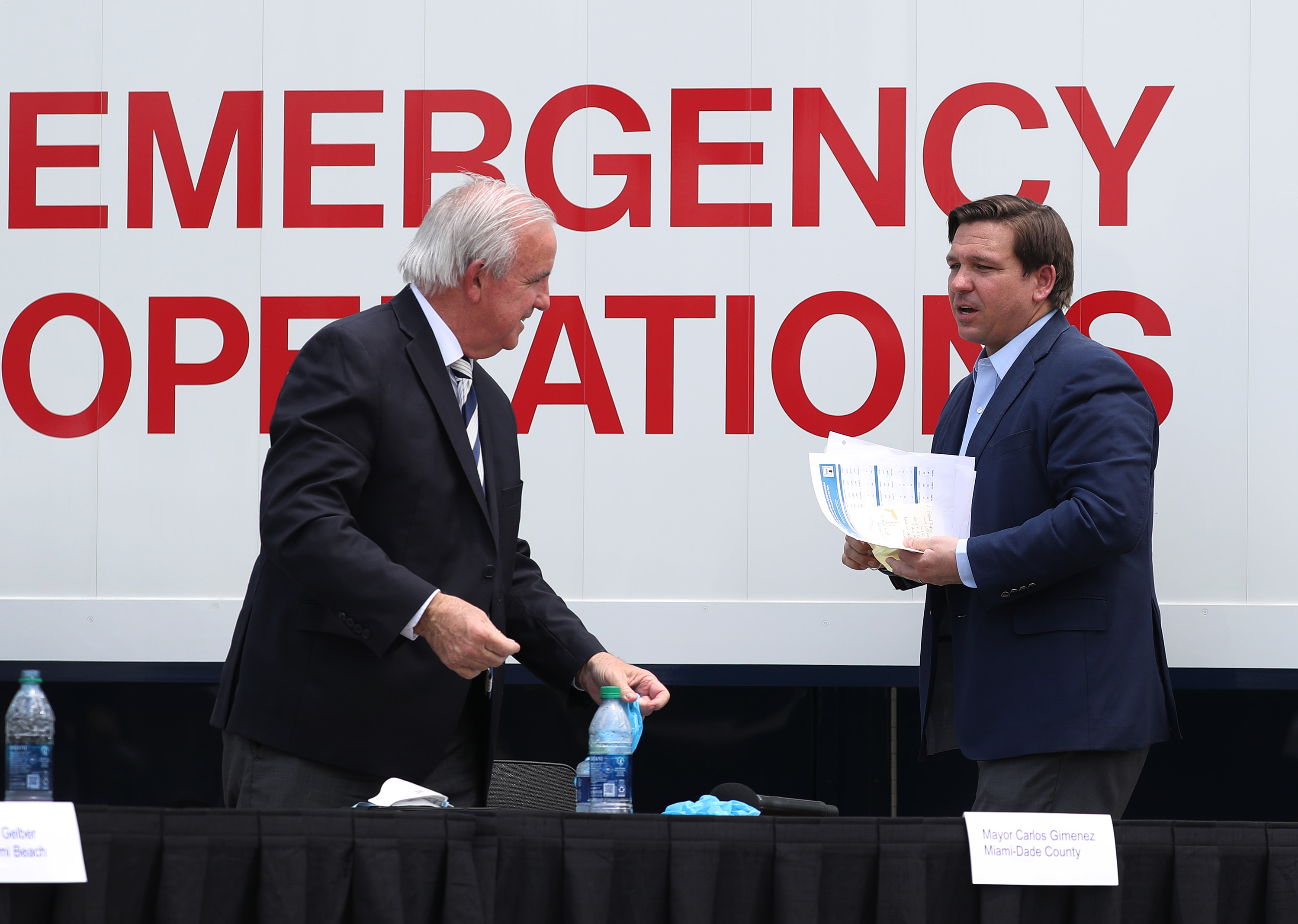

The bar itself shut down before spring break, but the event formally known as “The 35th Interstate Mullet Toss and Gulf Coast’s Greatest Beach Party” was still supposed to take place this weekend. However, on April 2—the same day Gov. Ron DeSantis issued Florida’s version of a stay-at-home order—the bar’s management announced it would postpone the event indefinitely.

“I think it would be difficult to keep them all 6 feet apart,” said Jenifer Parnell, the Flora-Bama’s head of marketing and public relations.

Fighting Covid-19 is a huge challenge for a state where the whole economy is geared toward gathering people together in one spot—the beach, a bubbling spring or a crowded theme park. And the state’s culture, from its bars to its politics, is focused on giving people whatever they want—the fantasy of fun and the freedom from any consequences. The idea of telling all those good-time Charlies to go home and stay there is so foreign to Florida it might as well be scrawled on the sand in Sanskrit.

Much of America might have been horrified that DeSantis, who possesses a Trumpian disdain for what he’s called “draconian” quarantine rules in other states, kept the beaches open until after spring break, turning the sand into viral petri dishes, but Floridians weren’t surprised. Spring break means big business here, so much so that normally pious Panhandle residents look the other way at the bars offering wet T-shirt contests and other ribald amusements.

Nor were Floridians shocked when DeSantis—a Yale graduate with a law degree from Harvard who has experienced problems with putting on both gloves and a mask—said he was fine with people going back to some beaches last week, as long as they did it in a safe way. Subsequent photos of crowds flocking to Jacksonville Beach as if the pandemic were over led to the hashtag #FloridaMorons becoming the No. 1 trending topic on Twitter on Saturday. He took the mockery in stride, telling the beachgoers, “For those who try to say you’re morons, I’ll take you over those who criticize you every day of the week and twice on Sunday.”

DeSantis is poised to become one of the nation’s first governors to re-open his state. Florida’s “Safer At Home” order expires April 30, and he’s set up a group of primarily business executives to advise him on how to do it, possibly on a region-by-region basis. But if he does, it will turn Florida into a different kind of petri dish: A test of what happens when an livelihoods-over-lives politics collides with what businesses, families and bargoers are really willing to do.

Even in a state that’s wired to cater to the whims of its 100 million annual visitors, there’s a tension between the eagerness of pro-business politicians like DeSantis to return to business as usual and the lawsuit-conscious cautiousness of a tourism industry that worries reopening too soon could do permanent damage to the state’s worry-free image.

Right now, instead of following DeSantis, many of the state’s businesses are nervously keeping an eye on the state’s biggest tourism moneymaker, Walt Disney World—although they lack similar resources for a long-term pandemic pause. The park closed March 16, well ahead of the governor’s order, and has yet to announce a reopening date. One analyst predicted that, because of a lack of a vaccine and an expected economic slump, Disney’s gates would remain locked until 2021.

In the meantime, like schools and strip clubs and other shut-down entities around the state, the Flora-Bama is trying to shift the Flora-Bama experience to the web, sort of.

Every day, and sometimes twice a day, the bar puts on a live, online concert by the various bands that would have been playing there had it been open. At the bottom of the screen are links for sending in money. They are doing that to help pay the salaries of the Flora-Bama’s 500 or so employees during the shutdown, Parnell said. Another link offers a way to support the bands, most of them local groups that have nowhere else to play right now, she said.

“We’re trying to keep the staff together,” she explained, “so when we reopen, we can go right back to serving people like before.”

No one knows whether that goal has the same chance that a flung fish has of crossing a state line.

Florida tourism dates back to the 1870s, when Uncle Tom’s Cabin author Harriet Beecher Stowe moved into a house on a bluff overlooking the St. Johns River and wrote stories and columns in northern newspapers encouraging everyone to come see the beauty of Florida. Her own house became one of the state’s first tourist attractions. Steamboat captains would charge passengers 75 cents a head to cruise past her home in hopes of catching a glimpse of America’s most famous writer sitting on her veranda.

As one historian has observed, there’s a straight line from the throngs gazing up at Mrs. Stowe’s Cottage to the throngs that normally would be jammed into Cinderella’s Castle. But right now, a skeleton crew at Disney World raises the flag over an empty Main Street USA every day. The Disney hotels are closed and so are its shopping centers. The most popular tourism destination in the world has furloughed 43,000 employees. Fantasyland just got real.

For longtime Orlando resident Jim Clark, a historian at the University of Central Florida, the sudden silence is reminiscent of the 1970s gas crisis, when the flow of visitors to Disney suddenly dried up. The economy blew apart like a house of cards built next to an oscillating fan.

“Hotels went out of business, homes were foreclosed on, condos were being auctioned off for $15,000—basically they were giving them away,” Clark said. It took years for the Central Florida economy to rebound, although when it did “we grew fat on the resort tax,” he said.

What makes it worse this time, he said, is that the shutdown is affecting so many more people, including whole families who immigrated from Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. They came to Central Florida, he said, because there were so many jobs available in the theme parks and hotels—only to see those jobs evaporate almost overnight.

All of Central Florida’s theme parks—not just Disney but also Sea World and Universal—have entrances off the same stretch of road, Interstate 4. As a result, I-4 is frequently so clogged with traffic that cars and trucks have a hard time moving.

Now, Clark said, “the interstate is eerily quiet.” When Clark took a drive on it last week, he said, “I allotted my usual 30 minutes for the trip and it took only 10.”

In the 1800s, Key West was the richest city per capita in the nation, thanks to wreckers who lured ships onto the rocks so they could loot them. It was an early version of the general Florida business model of attracting visitors with something shiny and then taking their money.

But during the Depression, 80 percent of the people living in Key West were forced to go on relief. The city government went broke and surrendered its authority to an administrator named Julius F. Stone Jr., chief of one of President Roosevelt’s New Deal agencies. His recommendation: Stop pining for the days when Key West had cigar factories and a Navy base. Instead, focus on becoming a tourist attraction.

Stone’s recommendation has worked for eight decades, so that now 2 million tourists visit the little island every year. About half of them pour out of cruise ships, although cruise-ship tourists stay only a few hours while the other kind of tourist will stay an average of three days.

But now the tourists have been banished. The home of “Fantasy Fest” has been turned into a ghost town—if ghost towns had a police checkpoint turning away would-be visitors as if they were looters after a hurricane.

Despite the ongoing damage to their economy, local government leaders say they have no intention of reopening the Keys before more testing is available and the counties north of them relax their own lockdowns. They don’t want to become a magnet for infected out-of-towners. “We are not out of the woods yet by any stretch of the imagination,” said Bob Eadie, administrator of the Florida Department of Health in Monroe County on Monday.

Arlo Haskins, who grew up in the town sometimes known as “Key Weird,” says the sudden emptiness reminds him of the quiet summers from his childhood, before the cruise ships began stopping by all year round. He took a long bike ride around the island one recent night and was amazed at the silence.

“It’s wild to ride down Duval Street at 10 p.m., a time it would normally be busy, and everything is totally dark,” said Haskins, executive director of the Key West Literary Seminar.

The pause is prompting some reconsideration among the residents of what the city should look like once it reopens. They’re pro-tourism, but not for all tourism, he said.

“A lot of people right now are thinking we’re better off without the cruise ships,” he said.

The reopening of Jacksonville Beach has spurred other parts of the state to consider following suit. Sarasota County commissioners voted unanimously to reopen their award-winning beaches, even if it means allowing another season of MTV’s “Siesta Key” reality show. Some Panhandle counties are considering it too. Mexico Beach, the Panhandle town nearly obliterated by Hurricane Michael, is also willing to risk letting coronavirus back in as long as the tourist dollars return.

But the Jacksonville Beach experience isn’t quite the economic boon that people might expect.

When Mayor Lenny Curry, former head of the Florida GOP, reopened the beaches last Friday “we saw a little bit of a spike, but there’s still only so much that people can do out here,” said Curt DeWitt of Beach Life Rentals.

The rules said if you were on the beach you had to keep moving—no sitting still and sunbathing. People rented bikes, he said, but they couldn’t use the umbrellas, chairs or kayaks that were also available. After the first day’s excitement, the number of beach visitors dropped.

Marti Tyrrel of the Beaches Business Association said a few beach restaurants might have seen some increased business, but that’s it.

Even if county officials in Pensacola vote to reopen Perdido Key’s beaches, don’t look for the Flora-Bama to crank up the party again right away. The owners are looking at both politicians and medical health professionals to advise them.

So far, they have yet to set a date for either returning to business or rescheduling the Mullet Toss, Parnell said, explaining “It’s all based around safety.”

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream