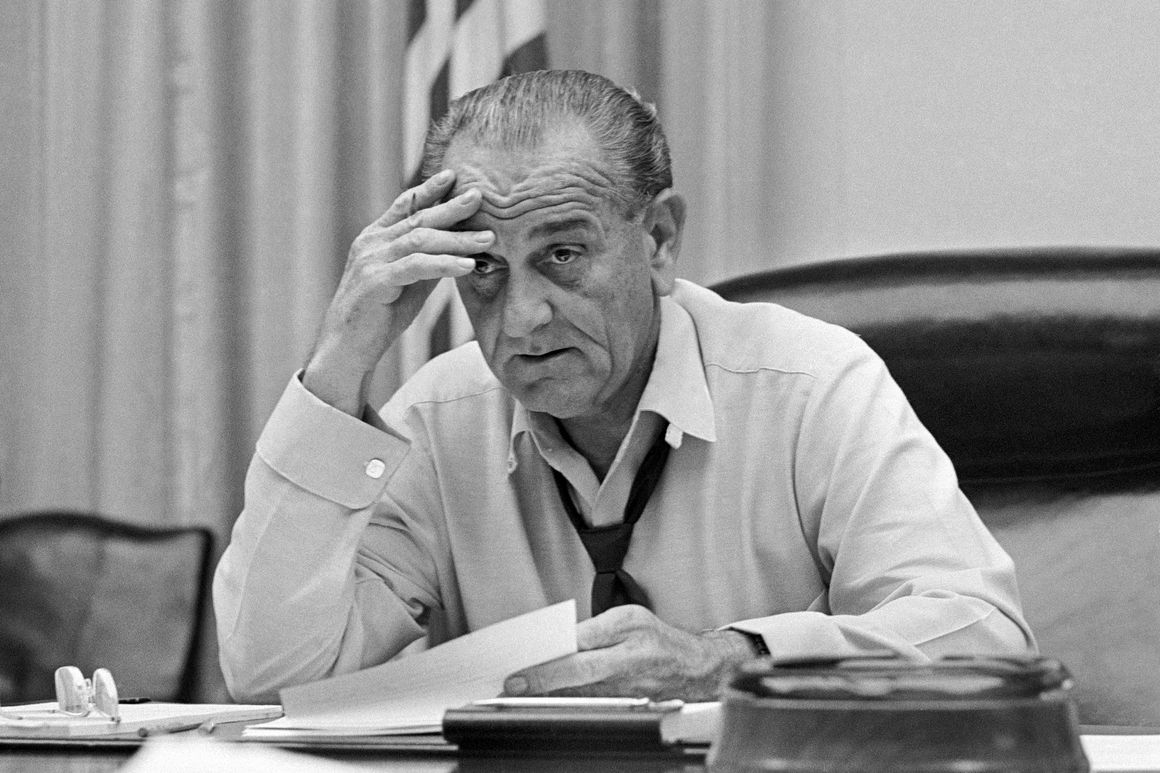

Nixon’s law-and-order message wasn’t just about urban riots. It was a repudiation of the governing party for its alleged part in the general unraveling of peace, prosperity and order. The late 1960s brought mounting inflation and racial unrest, campus uprisings, a sharp spike in crime, an emerging sexual revolution and court-mandated expansion of personal liberties—all set against the backdrop of a controversial war in Vietnam that the government seemed unable to win or exit. The incumbent president, Lyndon B. Johnson, and by extension, his vice president, Hubert Humphrey, had presided over the very social unraveling that many voters were eager to reverse. This was Nixon’s opening—his appeal to swing voters, especially.

Now, as in 1968, the violence of the past several days has revealed a broader pattern of social and political dissolution. Unemployment stands at 14.7 percent. Over 100,000 Americans lie dead of Covid, with no end in sight to the pandemic. Americans are bitterly divided by race, ethnicity and partisan affiliation. A foreign nation, Russia, has all but declared asymmetrical warfare against the United States. What the journalist Walter Lippmann said in 1968—“the world has never been more disorderly within memory of living man”—might credibly be said today. One key difference: Today, the candidate demanding “law and order” is the one who couldn’t preserve it.

Like Johnson before him, Trump’s is the party in power—the party that has failed to provide peace, prosperity and social order. Republicans control the executive branch, the Senate and the Supreme Court. They alone own the chaos, rancor and instability that many voters have come to abhor and dread.

Trump campaigns like Richard Nixon and George Wallace, but in reality, he is Lyndon B. Johnson: a man who has lost control of the machine.

To understand how urban rioting proxied for a larger array of social concerns in 1968, it’s helpful to rewind the clock four years, to 1964, when Barry Goldwater, the Republican nominee for president, attempted to blame Johnson for a general unraveling of social order. His strategy was best encapsulated in a 30-minute televised infomercial entitled Choice, which juxtaposed imagery of women in topless bathing attire, striptease clubs and pornographic literature with film footage of black urban rioters. Interspersed throughout scenes of lascivious pool parties and drug-addled youth, a man veers wildly and at high speed in a Lincoln Continental, throwing beer cans out the driver-side window, willy-nilly, for added effect.

The subtext was unmistakable: The same liberal forces that threatened to unspool the moral fabric of American society were driving racial minorities to lash out violently against public authority and private property. Or, for those who required direct narration: “Honest, hardworking America” was under assault. There were “two Americas, and you alone standing between them.” The film was technically the work of Mothers for a Moral America, but the GOP campaign played a hand in its production. Russell Watson, communications director for Citizens for Goldwater, freely acknowledged that it would tap the “prejudice” of “people who were brought up in small towns and on the farms, especially in the Midwest.”

Goldwater’s broadside didn’t make much sense in 1964. Inflation and unemployment were low. The Vietnam War had not yet claimed as many lives or generated as much discord as it would over the coming four years. The sexual revolution of the ’60s was still in its infancy. Campus unrest, while on the rise, was just beginning to accelerate. In short, one had to be “just nutty as a fruitcake,” as LBJ said privately of Goldwater, to find the argument compelling.

But the world changed quickly. The fringe argument that Goldwater levied against him in 1964 seemed all too believable by 1968, and in March of that year, Johnson declined to run for a second full term.

When Time magazine named half the country—“The Middle Americans,” roughly 100 million strong—as Man and Woman of the Year in 1969, it observed that a large part of the nation felt besieged. They were resentful of taxes and fearful of crime and inflation. They “cherish, apprehensively, a system of values that they see assaulted and mocked everywhere.”

In the aftermath of the 1968 election, two Democratic operatives, Richard M. Scammon and Ben J. Wattenberg, reached much the same conclusion, arguing that “many Americans have begun casting their ballots along the lines of issues relatively new to the American scene. For several decades, Americans have voted basically along the lines of bread-and-butter economic issues. Now, in addition to the older, still potent economic concerns, Americans apparently are beginning to array themselves politically along the axes of certain social situations as well. These situations have been described variously as law and order, backlash, antiyouth, malaise, change, or alienation.”

Nixon proved deft at tapping these raw emotions. His campaign was far more subtle than Goldwater’s had been, but still, the candidate railed against student protesters and urban rioters and promised to champion the interests of “forgotten Americans … non-shouters, the non-demonstrators, that are not racists or sick, that are not guilty of crime that plagues the land. This, I say to you tonight, is the real voice of America in 1968.”

Nixon was also more understated than another one of his 1968 rivals, independent candidate and former Alabama Governor George Wallace. An outspoken segregationist, Wallace trained his fire in equal doses on civil rights demonstrators and urban rioters, whom he conflated, and “over-educated, ivory-tower folks with pointed heads looking down their noses at us”—“when we get to be the president and some anarchist lies down in front of our car, it will be the last car he he’ll ever lie down in front of.” Student hecklers provided an easy target for Wallace, who delighted in highlighting the breakdown of authority and deference on America’s college campuses. “You young people seem to know a lot of four-letter words,” he sneered. “But I have two four-letter words you don’t know: S-O-A-P and W-O-R-K.”

Wallace made an easy target for liberals like Elizabeth Hardwick, a writer for the New York Review of Books, who mocked his “ill-cut suits, his grey drip-dry shirts … his sour, dark, unprepossessing look, carrying the scent of hurry and hair oil. … [His] natural home would seem to be a seedy hotel with a lot of people in the lobby, and his relaxation a cheap dinner.” Garry Wills similarly described Wallace’s “gritty nimbus of piety, violence, sex. Picked-on and self-righteous, yet aggressive and darkly venturous, he has the dingy air of a B-movie idol, the kind who plays a handsome garage attendant.”

But such condescension only heightened the governor’s appeal among white voters, many of them working-class, who were angry at the world—unsettled by inflation, the war, the protests and, to a large degree, by desegregation—and needed a place to direct their ire. Wallace proved a gift to Nixon, and not just because he siphoned off Democratic votes, especially in the South and Midwest, though that he certainly did. The former governor did the dirty work, loudly denouncing America’s chaotic descent. His fulminations afforded Nixon space to appear a moderate conciliator who would restore order and civility.

And it worked, if only by a hair. Nixon defeated Hubert Humphrey by just 0.7 percent of the popular vote.

If Donald Trump were the GOP challenger, running to unseat President Hillary Clinton, the violence sweeping over America’s cities might well have worked to his advantage. But he’s not. He is a deeply polarizing and, by historic standards, unpopular president who has overseen almost four years of unrelenting chaos and drama—white nationalist violence in Charlottesville and beyond, bitter attacks on the press, temper tantrums on (and now against) social media, a botched response to Covid resulting in 100,000 deaths and a broken economy, and criminal scandals of a volume not seen since the Harding administration. He was also impeached earlier this year, though that seems an eternity ago.

Some of the specific issues that animated public concerns in 1968 are different today. Covid instead of Vietnam. Unemployment rather than inflation. Rampant public corruption at a time when crime rates are relatively low. But the contours are the same—urban rioting captures a general sense of drift and social disorder that many voters are eager to reverse.

Unlike Johnson, Trump has proved stubbornly indifferent to the responsibilities of governing. He shuns expertise, science, data or any of the other assets a typical president avails himself of. He has little in the way of achievement that he can point to. He thrives on division, where LBJ sought to make America a more inclusive place for people of color, the poor and the left behind. In this regard, the two men are night and day, both in how they’ve executed the job and the moral bearing they brought to it.

But if Trump walks like Nixon and talks like Wallace, he looks a lot like Lyndon B. Johnson, a president who by 1968 seemed unable to put the country back together. If what today’s Middle Americans (or, in Nixon’s words, “forgotten Americans”) want is an end to the violence, drama and discord, this week’s unrest may ultimately benefit the one candidate who has built his brand on a basis of empathy, shared sacrifice and loss and a sunny belief in a better tomorrow. 2020 could be Joe Biden’s year.

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream