Eight years ago, Marisa Rodriguez made her first visit into San Quentin State Prison, a fortress-like facility north of San Francisco that juts into the bay and offers sweeping views of the city skyline. She had hesitations. She was early in her career as assistant district attorney for the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office, responsible for incarcerating people like the men inside.

She made the visit at the urging of her father, Steve McNamara, the former owner of Marin County’s Pacific Sun newspaper. He was a volunteer advisor for the San Quentin News, a newspaper written and published by those incarcerated at San Quentin, and over the past four years he had spent significant time inside the prison helping the men revive the newspaper after a 20-year hiatus. He visited as many as four or five times a week. Rodriguez, who knew about the serious crimes many of the men there had committed, couldn’t understand why her father spent so much time there. He invited her to simply visit the newsroom, meet the staff and judge for herself.

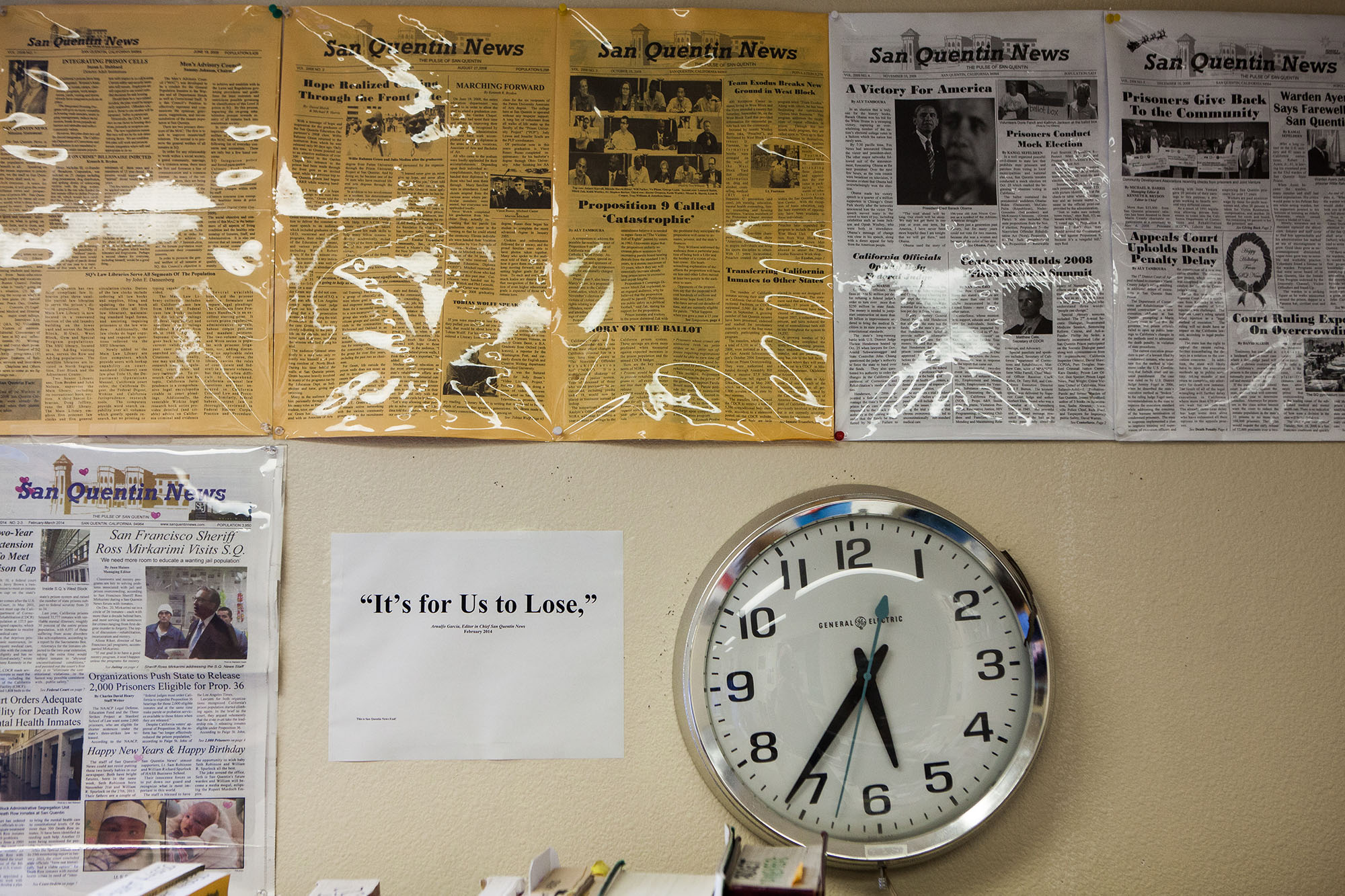

Rodriguez had arranged to meet Arnulfo Garcia, a tall man with a graying mustache and stately presence that outshone his blue prison uniform. Garcia, then editor-in-chief of the San Quentin News, and known as jefe by the staff, led her through a long, high-ceilinged room plastered with front pages of the newspaper and cluttered with notebooks and desktop computers. He told the story of how the staff had gone from producing the paper out of a closet in the prison education department, when it resumed publication in 2008, to operating this full-fledged newsroom, weaving in the story of his own rehabilitation following a drug addiction and 65-year prison sentence.

Rodriguez sat down with staff members and listened to stories about their path to this unlikely paper. The pattern she noticed was that they’d been trapped in a system, hit a low point and found programs like the paper to be part of the ladder back up. By the time Rodriguez’s visit was over, she was processing a mix of emotions—her own role as a prosecutor, a new sense of what was wrong with the whole system—along with one more policy-minded realization: “I realized this group of men was a potential think tank for criminal justice reform.”

In recent years, media by incarcerated journalists, and in particular by those at San Quentin, has been undergoing a kind a renaissance, growing inside and beyond prison walls—and in the process, it has begun to occupy a more important role in conversations about prison reform. Media made inside prisons has a bigger audience than ever before; Ear Hustle, a podcast by and about prisoners that launched in 2017, has had over 41 million downloads to date and was named a finalist for the first-ever Pulitzer Prize for audio reporting. Journalists in prisons and their allies in the community are increasingly taking the skills they’ve honed in prison newsrooms and published investigations, commentary and political stories in mainstream publications—an effort some outside advocates hope to spread to more prisons around the country.

Some, like those that Rodriguez spoke to in San Quentin, are also taking their stories directly to people in power, via forums that bring incarcerated men into conversation with district attorneys, policy makers and politicians. And perhaps most importantly, the work continues after prison: Incarcerated writers are also going on to work on repealing the laws that undergird mass incarceration after they are released, again using those same skills to shape a narrative about punishment that, until recently, most people weren’t open to hearing.

Narratives are hugely important to how the public and leaders understand people caught up in the justice system, starting the moment they hit court, often with a compelling tale of complicity told by a prosecutor. But with internet connections prohibited inside prison, as well as a lack of resources to produce media for outside audiences, incarcerated people have been largely excluded from having a hand in telling their own stories. But that has begun changing, in part because of innovative programs at some prisons. The storytelling of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated journalists has been key to public opinion shifts on prison reform in recent years, as the public and some policymakers have come around to the idea that the harshness of U.S. prisons might be inhumane, even counterproductive. Part of that change has been driven by the San Quentin newsroom—a place that continues to shape how Americans see prisoners, and how Americans see prison.

Newspapers were a common fixture of U.S. prisons since 1887, when The Prison Mirror was founded at Minnesota’s Stillwater Prison. By the middle of the century, most states had at least one prison-operated newspaper. Even early prison media attracted an outside audience: The Mirror drew advertisers from outside the prison, attracted thousands of subscribers, and billed itself as “the first important step taken toward solving the great problem of true prison reform.” The Angolite, perhaps the most well-known prison paper, was founded in 1953 at the Louisiana State Penitentiary. It was the first prison publication to be nominated for a National Magazine Award, for which it has been a finalist seven times. San Quentin’s first newspaper was Wall City News, which published regularly in the 1920s and 1930s. The San Quentin News was founded in 1940.

In the 1980s and 1990s, as politicians ran on platforms of cracking down on crime, prison populations swelled and budgets for educational programs for incarcerated people were slashed. Prison newsrooms across the country died in the following decades, from a high of 250 in 1959 to fewer than a dozen by 2014, according to a report by the Nation.

It wasn’t specifically a lack of money that shut down the San Quentin News. In the 1970s and 1980s, clashes repeatedly broke out between the journalists and prison administrators. In 1980, the warden fired everyone on the newspaper involved with an article featuring photography of bird droppings in the prison mess hall. The conflict ended up in court, with the judge ultimately siding with San Quentin’s journalists. In 1984, another court case—this one out of Soledad State Prison, in Southern California—once again affirmed the protection of free speech for prison newspapers. San Quentin officials, rather than complying, shut the paper down altogether.

The San Quentin News’ suspension lasted 20 years. In 2008, San Quentin Warden Robert Ayers Jr. came across vintage copies of San Quentin News and decided to bring the newspaper back. He once said the effort was an attempt to “rekindle some pride, some dignity to both the staff and inmate population.” He recruited a small group of outside advisors, all former journalists, to assist five incarcerated men in production of the first edition. The result was 5,000 copies of a four-page-long newspaper the incarcerated staff distributed by hand to each prison cellblock.

Despite being the most advanced prison newsroom in the country, San Quentin’s media makers still do not have access to the internet. (Staffers are granted access to one phone line outside of the prison’s pre-paid phone system, though it sits on the desk of a correctional officer and its use is limited.) The men work with a cohort of outside volunteers, many of them retired journalists, who help with research, training and editing. And now, Covid-19 has posed an additional obstacle to newsroom operations. In mid-March, the virus caused the media lab to shutter. It suspended all media produced inside, including the San Quentin News, and added production challenges for other projects. “When you look at journalists out in the free world, you see they are deemed essential workers,” said Juan Moreno Haines, one longtime San Quentin News reporter. “But when you look at the power dynamic here, we’re not essential to the operation here.”

Despite restrictions, media made inside the newsroom has flourished in recent years, beginning with the revival of the newspaper and spreading to newer forms of media. In 2015 Nigel Poor, a visual artist volunteering in the media lab on a radio project called the San Quentin Prison Report, had the idea to use some of the radio program’s equipment to produce a podcast. She worked with Earlonne Woods and Antwan Williams, both incarcerated at the time, to launch Ear Hustle in 2017.

Like most other media made inside the newsroom, Ear Hustle is more about telling the story of life inside prison than it is about investigating corruption or mismanagement inside, or pushing a policy agenda. “We’re not asking the questions that most people ask when they go into prisons,” said Poor. “We’re not asking people about their crimes, we’re not asking them how to reform prisons. We are showing those things through talking about families, what it is like to be in solitary, how you turn your cell into a home.”

FirstWatch, a video series founded by former San Quentin prisoner Adnan Khan and streamed on YouTube, showcases everything from men’s “prison’s journeys” to their thoughts on political candidates. As an attempt to show conditions of the four-by-ten-foot bunked cells that two people typically share at San Quentin, FirstWatch produced “Cell-Fies” in the style of MTV Cribs. To talk about lack of food options, they filmed a comedy video about peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. “I’ve been eating this lunch every other day for the past 15 years,” Khan’s voiceover chimes in. “We used humor to humanize people, but it was also an alternative way to say ‘look what they feed us,’” he told me.

Diverse stories about prison life are needed in a media landscape that often fails to quote incarcerated perspectives and paints prisons as dangerous and violent, noted Aly Tamboura, an early San Quentin News staff member who paroled in 2016. “You can’t change the hearts and minds of the voting constituency if we still use the dominant narrative that everyone in prison is a bad person who will get out and wreak havoc on our communities,” he said. “It’s imperative we start changing that narrative.”

“I wanted to talk about the three strikes law in every story,” Woods said about his work with Ear Hustle. He was convicted under that law in California, which gives defendants a prison sentence of 25 years to life if they are convicted of three felonies. (His sentence was commuted by former Governor Jerry Brown in 2018.) “But that’s not what this was about. It’s not about hammering people over the head that this policy is wrong. Instead we said, hey, let’s find someone who has a story. And maybe, it just so happened that story was about three strikes.”

The focus on prison life, rather than adversarial accountability journalism, is also partly due to the relationship that prison-run publications have to maintain with the administration. All of these newspaper, radio, video and podcasting productions are overseen by and must be cleared through the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Journalists at San Quentin are quick to point out they are not censored; the lab has put out stories that range from conditions in solitary housing units, suicide in prison, sex while incarcerated and men convicted of child abuse. But their work stops short of directly criticizing prison administration and avoids topics the administration might deem a threat to public safety, like prison gang violence. Media makers work out how to approach sensitive topics—like an Ear Hustle episode released this year about sex crimes against children—in consultation with San Quentin’s Public Information Officer, Lt. Sam Robinson, who, they say, ultimately takes the stance of supporting, not suppressing, work of the media lab. Still, explained Tamboura, “you have to play by the rules of the carceral system.”

As skills have grown inside San Quentin’s media room, those restraints are a big reason why incarcerated journalists and their allies are increasingly looking to establish direct channels between prison writers and mainstream outlets in order to publish more high-impact work.

Last year, Haines, the San Quentin News reporter, won a reporting grant as an independent journalist to report on the practice of placing sick prisoners in solitary housing units. His story was published in the criminal justice publication The Appeal. Haines recently published “Punished for Being Sick, The Sequel” in the wake of the coronavirus. With the San Quentin News shut down indefinitely because of the coronavirus, Haines continues to write for The Appeal; one recent report detailed how prison overcrowding affects coronavirus shelter-in-place measures.

Yukari Kane, a San Quentin News advisor, used her experience in the media lab to co-found the Prison Journalism Project to bring journalism education into prisons around the country. She aspires for more San Quentin journalists to write stories read beyond the walls. “I do think that to be heard, to be seen, to effect change, you have to be read in the publications our country’s leaders and influencers are reading and consuming,” she said.

But in bringing journalism programs like that in San Quentin to prisons around the country, she has found resistance. “The hardest thing is that prisons don’t necessarily want this,” she explained. Her co-founder Shaheen Pasha, a Penn State assistant teaching professor of journalism, expanded on the sentiment. “There’s a perception that if you bring journalism in, you’ll create a rebellion inside,” she said. “I keep hearing the term ‘burn it down’—that incarcerated men and women will use their stories to burn the whole system down.”

In light of Covid-19 Kane and Pasha pivoted from advocating for journalism programs inside prisons to requesting reports from incarcerated writers about the pandemic. They’ve published reporting, essays and poetry about Covid-19, as well as the recent police protests, directly to Prison Journalism Project’s Medium account.

Reporting and writing skills, Kane says, are not just useful in telling these stories; they can also create a culture of leadership and rehabilitation inside prison that resonates as prison media makers transition to freedom.

It has happened at San Quentin, where many members of the media lab go on to become reform advocates after their release—perhaps one of the strongest legacies of prison media on reform efforts. Making media while incarcerated pushes the men to learn the workings of the criminal justice system that’s dramatically shaped their lives. Miguel Quezada, a former managing editor who paroled in 2018, didn’t realize he was a juvenile lifer—the term for a juvenile under 18 sentenced to a life term—until he began researching and reporting on juvenile justice issues inside the media lab. After leaving prison, Quezada became a senior policy director focusing on juvenile justice for the nonprofit Communities United for Restorative Youth Justice.

Khan, founder of the FirstWatch videos, went on to found the nonprofit Re:Store Justice in 2017 with outside advocate Alex Mallick to reform California’s felony murder rule—the law Khan was sentenced under as a teenager. The rule allows a defendant to be charged with first-degree murder for a killing that occurs during a dangerous felony, even if the defendant is not the killer. Khan and Mallick joined other organizations across the state pushing to amend the rule.

An amendment to the rule went into effect in 2019, and Khan became the first person to be resentenced under the law he helped change. Just a few months after leaving prison, he was featured in the New York Times with a video op-ed arguing the felony murder rule should be amended in every state. He continues to run Restore:Justice with Mallick (now his wife) to focus national attention on life sentences and extreme sentences.

Woods, the co-host of Ear Hustle, who has become something of a public figure since his sentence commutation, is also engaged in criminal justice activism. He is part of Repeal California’s Three Strikes Law Coalition, a coalition in the early stages of organizing directly impacted people, their loved ones, grassroots organizations and community stakeholders to repeal the Three Strikes Law in California through a ballot measure in 2022.

Rodriguez’s connection eight years ago with editor-in-chief Garcia led to one of the most unexpected and effective reform efforts to come out of San Quentin’s media lab. Garcia long believed in the power of storytelling to prompt reforms beyond prison walls. What better way to improve the prevailing narrative about prisoners than to open a conversation with prosecutors, the people who are often the first ones to tell a story about an offender?

His idea and connection to Rodriguez became the San Quentin News Forums, which began in 2012 and continue to this day. Rodriguez initially brought a group of her fellow prosecutors inside the prison to sit in a large circle with the men in blue selected by Garcia. These men outlined what led them to a life in crime and their rehabilitation in prison—for many of the prosecutors, it was their first time hearing about what happened to a person after the guilty verdict in court. The gathering made such an impact on Rodriguez that she returned, this time with her boss, San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón. That followed with a visit by Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen and his staff. By the end of 2017, the newspaper had hosted 14 forums, including one with more than two dozen prosecutors from around the country.

Forums have expanded to host teachers, police officers, judges and politicians. During each, men from the media lab facilitate small-group conversations around issues like policing in marginalized communities and the effects of harsh sentencing. In a 2015 forum, Congresswoman Jackie Speier listened to more than a dozen incarcerated men tell their own stories of rehabilitation inside the prison. “I think that what you’ve done here is remarkable,” Speier told the group at the end of the meeting. “The ability to go from hyper-masculine to hyper-empathetic, that’s a skill set needed in the community.”

Garcia died in a car crash in 2017, two months after his release from prison. But his early collaborations with Rodriguez live on and embody the ways that prison newsrooms can expand into influential channels for reform of the system. Their district attorney forums led to the creation of the Formerly Incarcerated Advisory Board under the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office. After Tamboura left San Quentin he became a part of the first cohort. (Tamboura also joined the ranks of criminal justice reformers; he’s a manager with the criminal justice reform program at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.) The advisory board will continue under District Attorney Chesa Boudin, who took office early this year after campaigning on ending cash bail and no longer seeking three-strikes sentencing enhancements.

While reformers are reading and listening to more media made inside prison, and some advisers are hoping coverage can take on a more active role in reform, many of the journalists at San Quentin and their mentors seem them as just that: journalists, without a reform agenda. The rehabilitative potential of the newsroom is, for some, far more important than their role in stoking a conversation around reform. The recent book Prison Truth by San Quentin News advisor William Drummond bolsters the argument that the San Quentin News helps rehabilitate men under a working model between the men incarcerated and the prison administration. None of the men who left the media lab have returned to prison in the newspaper’s 12-year history, according to the book.

Rahsaan Thomas, the inside co-host of Ear Hustle who replaced Woods after he left prison, spoke to the rehabilitative elements of the media lab. “There’s a feeling of being accepted by the society you’ve been expelled from,” he said. “What makes us antisocial in prison is not just the criminal mindset, it’s that society rejected you. When you come to San Quentin, and you get accepted by the community, it’s an amazing amount of love. And how can you hurt a society that loves you?”

While San Quentin has a long-running, esteemed paper, it might be the smashing success of Ear Hustle that has been most inspiring for those hoping to re-create the magic of the prison’s newsroom. Inspired by that San Quentin podcast, a team inside Pelican Bay State Prison, California’s first supermax facility far to the north of San Quentin, in Crescent City, recently launched Unlocked, a new podcast.

The project began in 2019, when the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, encouraged by the success of Ear Hustle, approached the William James Association, an organization that already supports some arts-in-prison programs at Pelican Bay and other California state prisons, about producing a podcast from inside the prison. The William James Association hired Paul Critz, a longtime radio producer, to lead two classes of incarcerated men on the basics of production.

The project marks a notable shift in the kind of prisons the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation is partnering with to produce media from inside. San Quentin has a history of volunteers coming into the prison and assisting with programs like those in the media lab. Pelican Bay, on the other hand, has a notorious reputation for another reason: A harsher environment, not known for the kind of enriching programs found at San Quentin, and solitary housing units that spurred a major court case around cruel and unusual punishment inside prison.

That’s what the men wanted to talk about when Critz arrived for his first class. Pelican Bay’s podcasting team plans to tell the story over three more episodes. The first episode will talk about prison conditions before a 2013 hunger strike organized by the men in solitary housing units; the second will detail what happened during the hunger strike; and the third will outline how a series of reforms after the strike changed the prison. “They’re very interested in showing the culture has changed and that they hold a lion’s share of the responsibility for that change due to their activism inside,” Critz said.

In these early months of production, Critz and the men have navigated prison rules and restrictions, with one class working from an empty dining hall and another class working under the basketball hoop in the prison’s gym. They share a single laptop, mixer and two microphones. Critz has been unable to visit the men due to Covid-19 so the team will attempt to produce an episode about navigating the pandemic inside Pelican Bay over phone calls. The series on the hunger strike and its aftermath will pick up when they can meet in person again, according to Critz.

The desire to tell the story hasn’t waned. “The guys want to safeguard this podcast—they’re cognizant of what it means to them personally and also on a cultural level,” says Critz. “They’re not interested in kicking up a bunch of dust. They just want to tell the truth.”

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream