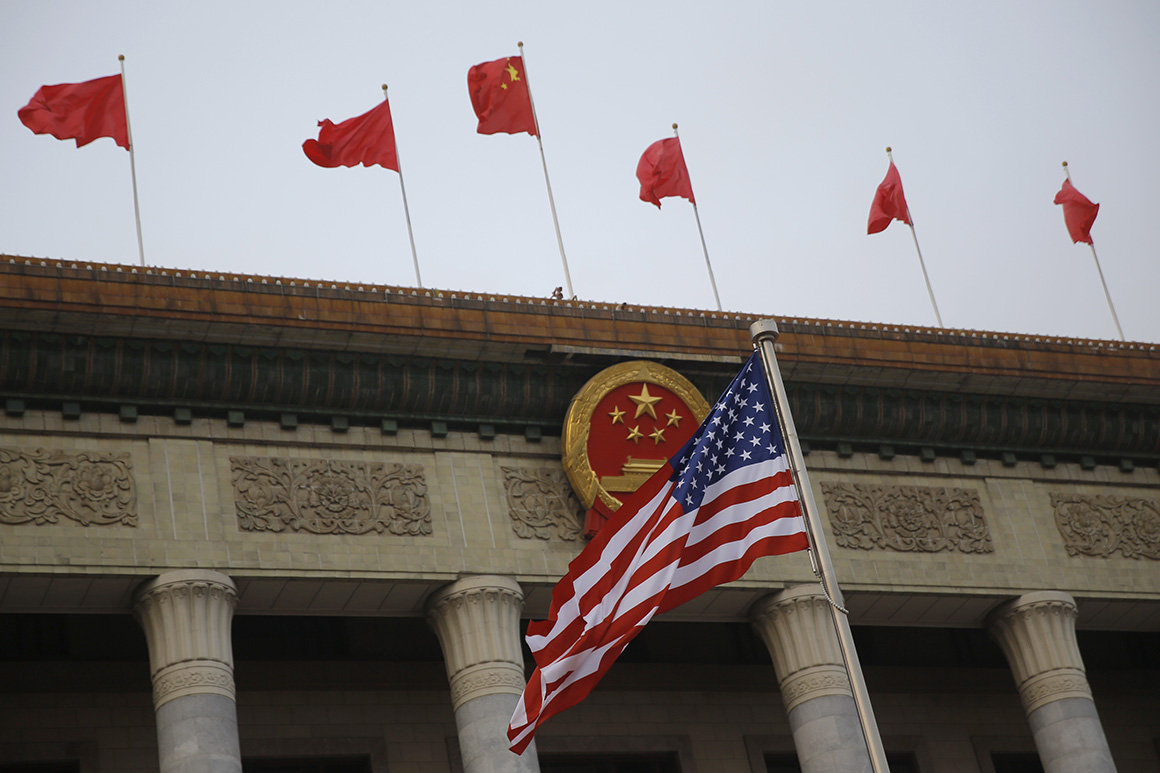

How far has the diplomatic relationship between the United States and China sunk? It’s gotten to the point where China watchers are increasingly invoking a fuzzy but extreme concept: “decoupling.”

In its purest form, the term refers to a halt in the flows of information, money, ideas, and people between the world’s two powers. And there’s plenty of evidence the two countries are headed in that direction. Washington is issuing new sanctions on China and its leaders nearly every week. Travel and diplomacy have virtually disappeared due to the Covid-19 pandemic, which began in China. Chinese investment in the U.S. has plummeted. And Chinese students in the United States are being made to feel increasingly unwelcome by the Department of Homeland Security and the FBI.

But how realistic is a pure decoupling – and what does decoupling, in any form, mean for our collective future? To help answer this question, I gathered a group of China experts with backgrounds in finance, trade, government and technology.

The consensus of our China Watcher roundtable video conversation: Full decoupling is a fantasy, and the probability of it happening is zero percent. However, even the process of partial decoupling will lead to major changes in the way all of us live our lives.

Joining me for the virtual discussion were Julia Friedlander, the C. Boyden Grey fellow at the Atlantic Council and former director for the European Union, Southern Europe, and Economic Affairs on the National Security Council in the Trump administration; Mark Wu, Vice Dean and professor of international trade at Harvard Law School, and Samm Sacks, a fellow at New America, a D.C.-based think tank, focused on cybersecurity and China’s digital economy and a fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai Center.

They described many changes, big and small, that will affect everyone’s lives as the U.S. and China pull further apart from one another:

— Hardware and software companies will have to make the “zero-sum” choice that platform companies have already had to make: are you American or Chinese?

— U.S. companies in China will have to “hyperlocalize” and wall off U.S. operations, creating overseas versions of themselves.

— Chinese companies thinking about going global will clip their expansionist ambitions to focus on “China plus friendly countries.”

— U.S. firms that previously used Asian supply chains to sell into the U.S. may have to “ring fence” them out.

— U.S. consumers will experience “whiplash” as China-sourced collateral goods and services, like bicycles, suddenly become much harder to get.

— Governments will issue more industrial policies, like subsidies, to attract certain industries and companies to shift or reshore their supply chains away from China.

— The “Data Wars”: U.S. data will stop at U.S. borders. Foreign companies will be banned based on blanket national security concerns.

— An end to seamlessness: When travelers step off an international flight and turn on their phone, they will no longer expect news, information or money to move seamlessly within it. VPNs and frustrating workarounds will become the norm.

— The digital Renminbi will rise. The world will rapidly move to adopt digital currencies, either privately organized or through central banks, part of a race to see who will control global payment systems.

— The dollar will experience stress as a reserve currency, as China tries harder to dodge or encircle the U.S. financial system.

The full transcript is below. It has been edited for clarity and brevity.

POLITICO: Is a U.S.-China decoupling possible? If it is, what would have to happen operationally for it to be so? And how long would that even take?

Samm Sacks: Both governments are ramping up the rhetoric and also the policy actions. I think we’re seeing this around China’s Cyber Security Law and the build-out of relevant standards and policies, and particularly a more draconian move by the Xi Jinping regime around digital content controls. This creates zero-sum choice in some areas where the idea of being a U.S. or a Chinese company becomes a zero-sum choice. I want to play devil’s advocate for a moment and argue that the most concrete effects of decoupling may have already occurred. When we talk about companies like Facebook and Twitter and Google that are really in the sort of social media platform area [and are all blocked in China], that zero-sum choice has already been made. But I would argue that there are a number of companies in hardware and software that have been straddling that divide for a long time, and I don’t see necessarily moving out of China anytime soon. And it’s interesting that the Chinese government has threatened but has yet to actually activate the so-called unreliable entities list. We have not seen the degree of retaliation against U.S. companies that I think some would have anticipated. And, in part because for these companies that managed to straddle the divide, they continue to meet demand in China that domestic industry has not been able to meet. So until we see domestic industry be able to really step up and replace some of those suppliers, I don’t see that unreliable entities list. I don’t see that further decoupling moving in the near-term.

But what is this going to mean going forward? I think we’re going to see companies hyper-localize in China unless they want to pull out. In some ways, [TikTok owner] ByteDance was ahead of its time in firewalling the overseas version of its app TikTok from [Chinese app] Douyin. And we can debate whether or not that firewall exists or not. But the idea that you create an overseas version of the platform that’s firewalled ostensibly from a domestic app, we’re going to see more of this hyper-localization or in order to straddle the divide.

Mark Wu: When we use the term decoupling, we have to think of it as a spectrum. There are a range of options and it will differ depending on which sector. What’s the nature of that company? It will also differ based on where that company earns its revenue globally. One possibility is definitely the zero-sum choice that Samm alluded to. But for other companies, this is a question about simply not putting all your eggs in one basket. So you’ve seen some companies depend overwhelmingly on either Chinese or American suppliers. And now [they are] thinking, we better have other sources in case unexpected developments happen. Then there is another alternative, which is to say nothing’s going to change about how we operate currently, but we may have to change our future plans.

Chinese companies right now who operate with a “China for China” type of strategy may now be thinking about going towards a “China for the world” strategy.

Similarly, on the U.S. side, I think some may have thought, well, we can supply from Asia using China as an integrated part of our supply chain to supply for the U.S. market. They may have to look more at ring-fencing strategies to make sure that they continue to be able to have access to the U.S. market. It will really depend on the sector. There are a lot of security and dual use technology concerns.

Julia Friedlander: First of all, I would say that decoupling is a very hard thing to define. And I think it’s a bit dangerous to sort of use it in everyday nomenclature at this moment, because especially looking at the U.S. administration at this time, you have advisers who range from defenders of the free market to those who would advocate a modified return to autarky. So you’re witnessing right now a very iterative process in the Washington establishment, trying to decide what does this actually mean and where are the limits.

I think it’s important to understand what the implications of any of these measures would be for the U.S. economy, especially during a time of Covid-19-induced global economic crisis. I’m considering that Hong Kong and Shanghai are a vital financial hub for U.S. manufacturing and for financing supply chains. This does not come with significant downsides to the United States. Within the next week or so, if I remember correctly, the Department of Treasury is set to reveal a release of the results of its Capital Markets Working Group, which is a meeting of regulatory agencies in the U.S. government to decide what actually could we do in terms of removing Chinese entities from the U.S. stock market. So we’ll see what the S.E.C. and others have in store. And that dovetails with the Department of Defense’s submission to Congress of a list of Chinese firms that pose a national security threat to the United States government due to their association with the Chinese military. Several of those are listed in New York.

So this is what you see: a bunch of iterative processes. You’re trying to determine what decoupling might mean. I think it’s also interesting that on the European Union side, you see a capital markets reform and also a trade policy review which are looking at you really applying internal E.U. market standards to third party participants. And so while on the European side, they may not be using anti-China rhetoric to the same degree that we do or feel comfortable doing in the United States at this time, on the regulatory side, they really are acting in tandem.

POLITICO: What does this process of decoupling mean for the lived experience, for your average American person or your average Chinese person?

MW: I think one thing we’ve already gotten used to and we’ll probably have to continue to be used to is whiplash. Take bicycles. This spring they have become very difficult to get, partially because of Covid-19, partially also because our supply chain is largely concentrated in China. So you’ll see lots of collateral goods and increasingly services [becoming harder to get].

There will be more industrial policies put into place. Certain industries and certain companies will have subsidies made available to them in order to try to induce the types of changes in the supply chains. We’re seeing the Japanese government, for example, use these to encourage reshoring supply chains.

SS: I think that the U.S. is moving towards its own version of cyber sovereignty with the idea that national walls can be put up around data and cyberspace. TikTok is just the latest example. But I think that there has been movement afoot. I’m calling it the “data wars.” It’s the idea that U.S. citizen data should stop at the physical border of the U.S. And that not just Chinese, but any company from a country that deems an adversary, that company can be banned based on blanket national security justifications focused on cyberspace.

What does this mean tangibly for an ordinary person? I think about what happens when I show up at the airport in another country and I open up my cell phone and I expect seamlessly to be able to send a message to friends and family, transfer money, check the news, be able to pay for things on the phone, whatever. These are sort of things that we’ve gotten accustomed to, our data flying seamlessly around the world without respect to national borders. And I think that we’re beginning to see more walls put up around data that are going to make that kind of seamless interaction in the digital economy a thing of the past.

JF: I think one thing we also have to keep in mind right now is the very rapid movement towards the use of digital currencies, whether privately organized or through central banks. This is going to be one roving standoff area between the United States and Europe and China: a race to see who’s going to control the payment systems. We’re used to dollar-based finance, for the large part, globally and the use of the dollar as a reserve currency. But the more that we press, through sanctions or export controls or the use of access to U.S. dollar denominated markets in New York, the more you’re going to see an effort on the other side to elevate the role of the digital Yuan or the Yuan, in general, to encircle or avoid the U.S. financial system.

So you really have to find the right balance, because if you want to use the tools of U.S. policy, you can’t overuse them to the point that then they lose their potency.

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream