“This is going to be the rest of my life. They want me to die here.”

Demel Dukes, a 41-year-old Detroiter and father of four, was sentenced to life in prison 18 years ago. For the past five, he’s been at the Chippewa Correctional Facility in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, where hushed brick walls divide more than 1,000 beds inside from peaceable rural terrain outside. Just east on I-80, his own name happens to mark the landscape: Dukes Lake is half a mile away, nine acres of freshwater, popular for fishing. To him, it might as well be in another state.

Over the years he has seen depression and despair swallow grown men alive, and has confronted the questions that hang over people facing life sentences. What do you do with this time? How do you carry responsibility for yourself and the burden of never-ending exile, while also—well, living?

For his first nine or ten years inside, Dukes steered clear of the prison groups that might have offered answers to those questions, leery of “some shady characters.” He preferred to spend time in the law library. But one day, at the invitation of a friend, he went to the general assembly meeting of a group called National Lifers of America. There, Dukes saw incarcerated men discussing leadership skills and legislation on criminal law. It felt, he says now, like people were genuinely interested in educating themselves and one another—not just filling time, but meaningfully engaging with the world. The message of mutual uplift, he said, was “right up my alley.”

The NLA, founded 40 years ago by five men at the State Prison of Southern Michigan in Jackson, Michigan, is a pioneer in the movement for prison reform driven by people who are themselves in prison. There are nearly no records to take the full measure of such groups, but the NLA, despite the name, is largely confined to Michigan, and it’s on the leading edge of organizations like Veterans in Prison, Jailhouse Lawyers Speak, and the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee. Dukes discovered one of the NLA’s purposes at his first meeting: It’s a network for mutual support and growth in prisons, where the people who live their longest tend to have the fewest available opportunities.

The group also organizes for social change, sometimes with the help of outside reformers, developing their family members, friends and allies on the outside into a political force—and culminating in a statewide effort that could put one of the Lifers’ longtime priorities on Michigan’s November 2020 ballot.

The idea that people who have lived experience should take the lead in determining the priorities and polices that affect their lives is increasingly embraced in modern social movements. But for criminal justice organizations, this is difficult to practice, given the inherent restrictions of people in prison. Incarcerated people can’t serve on staff in the usual way, or on the board of directors, or canvass door-to-door. Their freedom to assemble, protest, and organize is severely curtailed. They can’t vote. While formerly incarcerated people may have leadership roles at advocacy organizations, as well as family members of those inside, they’re the first to tell you that they can’t speak for those who are inside today. And people with long, life, and indeterminate sentences are particularly at risk of being shut out of the conversation, even though they have the most at stake.

The NLA is an alternative model. “It’s ran by us and created by us,” says Dukes, who is now the vice president of the NLA’s Chippewa chapter, #1016. Today, its scope is difficult to measure, as full membership tallies aren’t kept, but it has chapters at every prison in the state of Michigan. For much of its history, the NLA has pushed a steady stream of policy projects, notching the occasional reform. Central to this is an organizing approach that transcends the boundaries of a prison’s walls to build inside-outside coalitions—and bringing prisoners’ voices into debates that are often about them, but rarely include them.

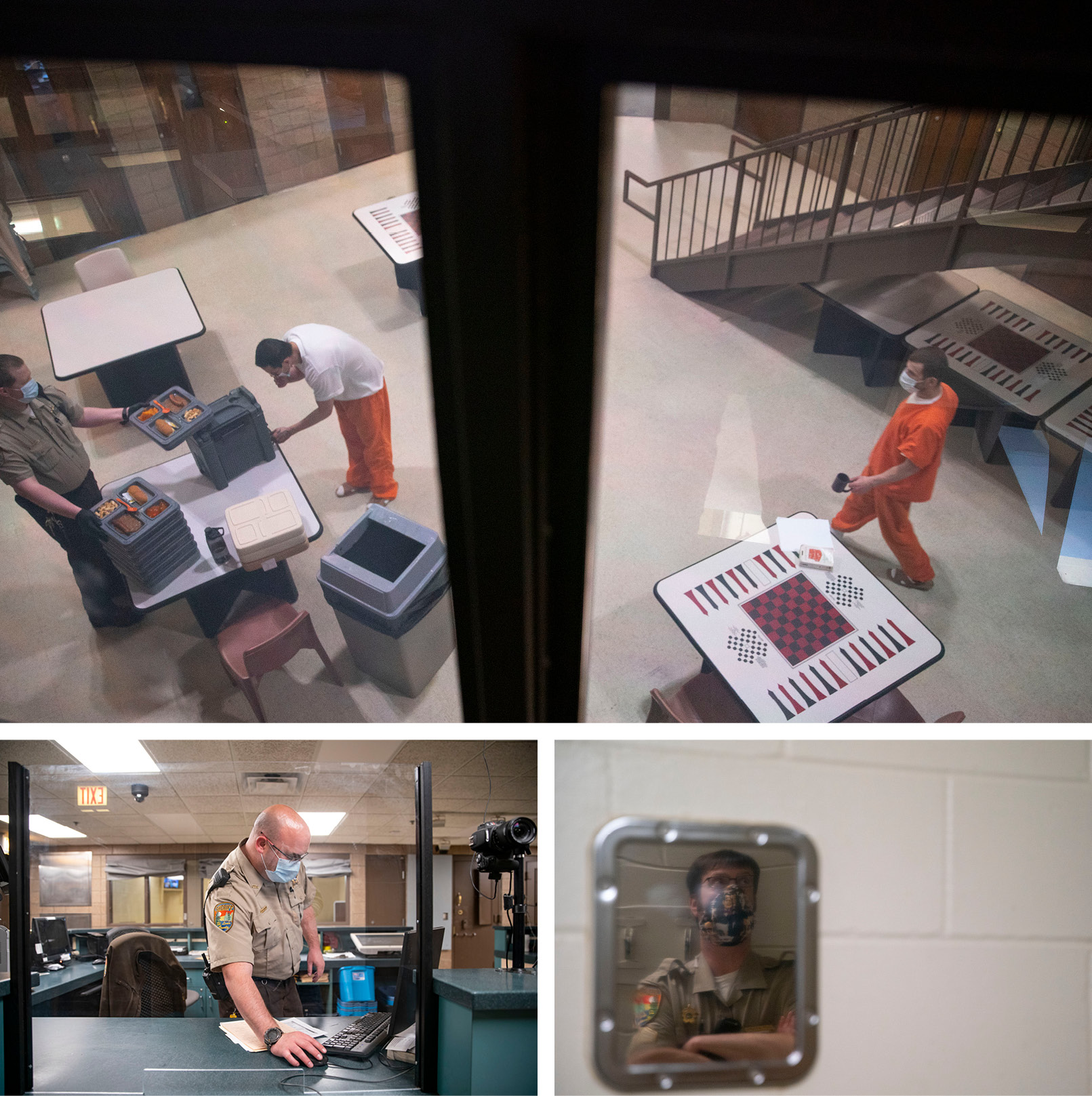

But in 2020, everything changed. The coronavirus pandemic was an immediate health concern, that, for a time, put Michigan first in the nation for Covid-related prison deaths. It also moved the NLA’s project of coalition-building from the “challenging” category to the nearly impossible.

In-person visits are essential to connect, but they’ve been suspended since March, along with large meetings and programs. Phone time is much more difficult because of a coronavirus response that restricts opportunities to use them and far more people making more calls. “There’s pretty much a run on the phone, a bottleneck,” Dukes said.

Likewise, uncertainty clouds the ballot initiative to restore “good time” credits, which reduce an incarcerated person’s sentence as they serve time without incident and participate in self-improvement programs. By law, the campaign must gather 340,047 valid signatures in order to appear on the November ballot. But with stay-at-home and social distancing orders this spring, garnering signatures by the mandated deadline was essentially impossible. The coalition had collected more than 200,000 signatures by mid-May—and aimed for 300,000 more—when it filed a lawsuit aimed at forcing the state to adapt the rules. On June 11, a federal judge sided with the coalition, ruling that, given the circumstances, the ballot requirements are unconstitutional. The state, which has appealed the decision, was given 60 days to resolve the matter. The coalition continues to collect signatures.

But while the pandemic has made organizing and programming much harder, the extraordinary circumstances of this year are a portal into another possible world. Previously unthinkable changes to criminal justice have, suddenly, become real. In the name of public health, states have released people from prisons and expedited the parole process for those with little time left on their sentences; many jails have released people en masse. In the last three months, Michigan reduced its prison population by 5.2 percent—sometimes by accelerating parole reviews, and sometimes by making use of “good time” credits that were grandfathered in before the practice was banished in 1998. Jails and courts delivered fewer people to prison, too, so that altogether, there are about 2,000 fewer people in Michigan’s prisons today than in March.

At the same time, the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis has pushed civil rights advocates and local officials throughout the country to imagine wholly new ways of protecting public safety and reckoning with the justice system.

Whatever happens next, people on the other side of the wall—including NLA members who have no release date—want to be part of creating it.

It is impossible to summarize the life of Ronald Simpson-Bey without it sounding like the stuff of movie scripts. The Flint native grew up in a middle-class family: his dad, a schoolteacher; his mother, a homemaker; the RV motorhome, a mainstay for epic road trips on summer vacations.

Simpson-Bey, a state champion sprinter, went to Eastern Michigan University on a track scholarship in 1975, but lost it when he broke his ankle. He returned to Flint to take college classes while working at General Motors as a tool and die maker. At night, he was “living the street life,” he said, feeling like a real-life incarnation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. This took a particularly dark turn in October 1985, in the aftermath of a visit to a surveilled drug house with three other men, shots from their Buick Regal were fired at police officers.

The father of four was sentenced to 30–50 years for assault to commit murder and a firearm felony, which was well beyond the sentencing guidelines of 10–20 years. “You don’t absorb it,” Simpson-Bey said. “You get numb to it.”

He was delivered to the state prison in Jackson. Once the largest walled prison in the world, the sprawling complex fit nearly 6,000 people behind 33-foot-tall walls that long-ago prisoners had built themselves. Facing thousands of days in a place like this, Simpson-Bey knew he needed purpose. He joined the NLA shortly after his arrival, and became a serious paralegal. His work included a class-action lawsuit that took 17 years to resolve and writing the habeas corpus that won his release in 2012.

Over the years, as Simpson-Bey moved to different facilities, he became president of every NLA local he participated in, finding that his lines of work overlapped. Lawsuits needed evidence, which might well show up in the copious notes, marked with dates and times, from NLA meetings where members discussed day-to-day issues.

“The basis of most prisoner issues has always been political,” wrote David K. Hudson-Bey about the NLA in his book Incarcerated Dad. (He isn’t related to Simpson-Bey; the “Bey” suffix is associated with a Muslim group in prison.)

The NLA works with a curious mix of supports and restraints. Full meetings are generally held once a month at individual correctional facilities, while committees meet separately to focus on legal issues, special events, and other topics. Simpson-Bey remembers a committee working on care packages to provide toiletries to people who enter prison without basic necessities.

Coordinated activity between independent chapters at different prisons isn’t sanctioned, but there is inherent cross-pollination as people are transferred. People with sentences of ten years or less qualify for associate memberships, and can access programming, but can’t run for office on a chapter board. The NLA can’t accept membership dues or donations, but it gets funding from the Prisoner Benefit Fund, which is money collected, for example, from phone calls and commissary services. Chapters are required to be affiliated with an outside sponsoring organization—for example, the American Friends Service Committee sponsors the NLA at Michigan’s only women’s prison—but they lead their own groups. Demel Dukes has served on chapter boards over the last decade, and he’s become fond of bylaws and parliamentary procedure. “I found myself in my spare time watching C-SPAN and I kind of liked it,” Dukes said.

In this way, the NLA is able to set its own priorities. “NLA gives people inside the power to build programs,” said Natalie Holbrook, director of the American Friends Service Committee’s criminal justice program in Michigan. “That’s what’s wonderful about NLA.”

It’s not a small point. For George Mullins, Jr.—and everyone else I spoke with—programming for lifers is of the utmost importance. Mullins is a Detroiter on the cusp of his 50th birthday, and vice president of the NLA at the Gus Harrison Correctional Facility in Adrian. “In my opinion,” said Mullins, “ninety-nine percent [of incarcerated people] have the fight knocked out of them because of the shock factor of this environment.”

After spending more than half his life behind bars, Mullins can tick off what he sees as sorely needed programs: economic literacy, conflict resolution, learning how to recognize trauma and triggers, connecting with family, positive reinforcement. It’s too easy to languish otherwise, watching each year roll by like heavy fog.

The MDOC does offer skill-based classes and rehabilitation programs, including classes about domestic abuse and violence prevention. But they are effectively open only to people in the last couple years of their sentences, and so they don’t meet the needs of lifers. College classes are more accessible, generally available to those in the last five or six years of their sentences, said Dwight Henley, president of the NLA chapter at the Macomb Correctional Facility in Lenox Township. [In disclosure: I facilitated creative writing and improv theater workshops in Michigan prisons for many years, with the longest tenure at Macomb. I am not a current volunteer and had no previous acquaintance with anyone interviewed from prison for this story.]

“They don’t say we’re not on the list because they can’t discriminate, but they put us at the bottom of the list,” Mullins said. “Those with a shorter time go above us, so technically we’re on the list.” The message, as he interprets it, is that society gives up on people like him: “You’re never going home, so you don’t need this.”

Jim Knaack, a prison counselor at Lakeland Correctional Facility in Coldwater, and Chris Gautz, the public information officer for the Michigan Department of Corrections, affirmed that there is limited access to programs for lifers. Gautz said that people nearing release are prioritized so that the information they receive is as up-to-date as possible before they re-enter their communities. Knaack noted that parole requirements call for certain classes to be completed before a person can exit prison, which is why people nearing a parole review are given priority—it gets them out sooner.

The Lakeland facility, Knaack said, is “getting caught up” on a backlog, and access will improve over time. But also, he said, “it comes down to resources and time, and then our requirements,” which pushes lifers down the list. One of the reasons he began working with Lakeland’s NLA chapter, he said, is because “these guys don’t have any programming, so I wanted to work with them to help them develop programming.” They teach their own groups, but he assists with, for example, scheduling speakers who come in and offering guidance. “We have a good group right now and, boy, they are very interested in it and very hardworking in getting their programs running,” he said.

In the meantime, NLA members are looking for alternatives. Mullins’ chapter negotiated to co-facilitate a life skills class, he said. Over at Macomb, Henley’s group wrote a report about programming issues and pushed it out to a bipartisan mix of state legislators, hoping it will inspire support for expanding resources in prisons. And up at Chippewa, Terico Allen, who serves on the NLA board, said that meetings are a forum for long-timers to mentor young men who maybe haven’t been treated well by their families or peers, and give them encouragement. “I been here 33 years … I understand where they’ve been,” Allen said. Even something as seemingly simple as teaching them proper hygiene, when no one showed them, makes a real difference.

The NLA is also empowered to create its own programming. The Lakeland chapter did a cancer walk last fall. The chapter at Muskegon Correctional Facility donated blankets to a local nursing home awhile back, while the one at Gus Harrison gave winter clothing to schoolchildren. Sometimes chapters host mock public hearings and interviews. They dig into restorative justice, or host classes on financial literacy and English as a Second Language. Representatives from the American Friends Service Committee have been invited to train members in facilitation techniques and updates on public policy issues. A judge might be invited in to talk about the legal process.

Simpson-Bey’s chapter developed workshops for commutation and parole readiness. “Most people in prison have a misunderstanding of the parole process. Totally unprepared and not ready,” he said. The NLA created a training curriculum that covered setting up a home plan—that is, a plan for where and how they’ll live if they’re released—and understanding that parole hearings are not as a second trial where a case is re-argued but instead an opportunity to express empathy, responsibility and growth.

At Chippewa, Demel Dukes and his peers went through training with AFSC’s Natalie Holbrook to develop a similar curriculum. It also offers a Compassion and Accountability class, which guides people in identifying with the emotions of those affected by their actions and creates new opportunities for community connection. In partnership with the Pure Heart Foundation, members write anonymous letters of support to the children of incarcerated parents. They also initiated a letter-writing program with incarcerated women after reaching out to Gigi Blanchard, who runs a literacy program at the Rikers Island jail in New York. They read about Blanchard in O, The Oprah Magazine; one of the NLA facilitators has a monthly subscription. “A lot of guys are talking about Oprah!” said Dukes.

Another issue of O featured a quote from Bryan Stevenson, president of the Equal Justice Initiative, that struck a chord: “You are more than the worst thing you’ve ever done.” It was so powerful, Dukes said, that it is now the affirmation that members of his NLA chapter recite at every weekly meeting.

After Ronald Simpson-Bey left prison in 2012, after 27 years inside, he took a break. He worked with his brother in a Flint garage. He spent time with his daughters. For his only son, though, his release did not come soon enough. Years before, he had been murdered while on his way to visit Simpson-Bey in prison for Father’s Day. Simpson-Bey lobbied for the 14-year-old who committed the crime to not be sentenced as an adult. (He wasn’t.)

In time, Simpson-Bey returned to his life’s work. First at the American Friends Service Committee and now as outreach director for JustLeadershipUSA, he’s serving the same folks he did before, only this time from the free world.

That sort of cross-ways organizing, where people with personal experience of the yawning expanse of prison are active rather than passive agents, takes many shapes.

Shawanna Vaughn was born in prison. Her mother, who suffered from drug addiction, was incarcerated in California. Her brother is incarcerated, another brother was murdered by a teenager and Vaughn herself spent some years in prison for robbery. “I understand what it is when prison is a generational traumatic experience,” Vaughn said. Now a Bronx-based organizer, she created the nonprofit Silent Cry, Inc. to intervene in what she calls “post-traumatic prison disorder.”

Vaughn has been lobbying state legislators, especially in New York and Michigan, to take up a bill that mandates trauma-informed therapy by vendors who are not direct employees of the Department of Corrections. People with long and life sentences are her biggest concern. “We have juvenile lifers coming home. We have wrongfully convicted people coming home. And while they were incarcerated there were no mental health services that were adequate, that were restorative. It’s not there.”

Dukes echoes the need for that. “Many of us, whether they know it or not, don’t forgive ourselves for being just like our fathers, or the mess-up of the family,” he said.

Vaughn hinges her work on what she hears from people who are now incarcerated. Her lobbying work, for example, was informed by results from a survey NLA members at the Gus Harrison facility developed about post-traumatic prison disorder. “They got together and created a survey. They actually made copies of it and passed it around. As of now, they have sent me about 40 surveys back.”

“They are participating in their own advocacy,” Vaughn said. “They are doing what they can from the inside.”

Amani Sawari, the campaign coordinator for the “good time” ballot initiative, said that this sort of self-determination is essential. NLA members informed the campaign before it began gathering signatures, Sawari said, by distributing a seven-question survey to their members about long prison sentences, collecting about 300 responses over two months.

“We cannot create a system that serves people adequately—people suffering from trauma, people who are victims of violence themselves—we can’t serve them if we’re not listening to them,” she said. “Not just listening to them, but centering them.”

That’s easier said than done, however. It’s not as if every person who is incarcerated stands unanimous on every issue. Internal politics can thwart an NLA chapter’s best intentions. Phone and electronic communication are expensive, calls are allotted in 15-minute increments, and inside-outside contact is monitored; Vaughn said that she’s mailed a lot of letters that have been rejected. NLA members also tend to be an especially engaged segment of the population, and perhaps not always representative of the whole. Ronald Simpson-Bey remembers a pattern familiar to any organizer, inside or outside: the same 10 people show up for everything.

This year, the coronavirus pandemic has brought with it a whole new set of obstacles, with visits and meetings restricted, and phone time that can feel like a competitive sport. But the NLA is still active.

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan was lightly touched by Covid-19 this spring, so, while general meetings of the NLA Chippewa chapter are suspended, the six members of its executive board have been able to continue meeting regularly, with some social distancing. “It’s like a well-oiled machine,” Dukes said. In addition to discussing programs, they are also considering how to petition for those most at-risk from the virus, advocating for the compassionate release of “elderly guys literally in their seventies.” Classes have been able to continue, but the time slot is cut in two, with half the group going to the first hour and half to the second hour—smaller classes allow for better social distancing.

Elsewhere, Dwight Henley said that his group at Macomb just drafted a proposed bill, modeled, he said, on similar ones in New York, Illinois and California. It suggests a public hearing process for those who have served at least 20 years of a long and indeterminate sentence, or 25 years for people with non-parolable life sentences. They would also have to be at least 50 years old.

Will a legislator take up such a bill? Will the push for high-quality mental health services in prisons find success? Will the “good time” initiative appear on the ballot this November, and if so, how will voters respond? How will the ongoing agitation for excellent programming available to lifers fare?

If this year has underscored anything, it’s this: No one knows what will happen. In some ways, this uncertainty is a strength. It loosens the hold of the assumed way of doing things and opens up new possibilities.

Danny Jones, a juvenile lifer and NLA member who was released last year after resentencing, said that the coronavirus has proven how many people can be released or diverted from prison without incident. “These should be done in light of Covid-19, but should have been done years ago.”

This is a time to re-calibrate what is acceptable, as Shawanna Vaughn put it. “That is my new question,” she said. “Who gets redemption? Who gets forgiveness? Because it’s not afforded or given to everyone.”

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream