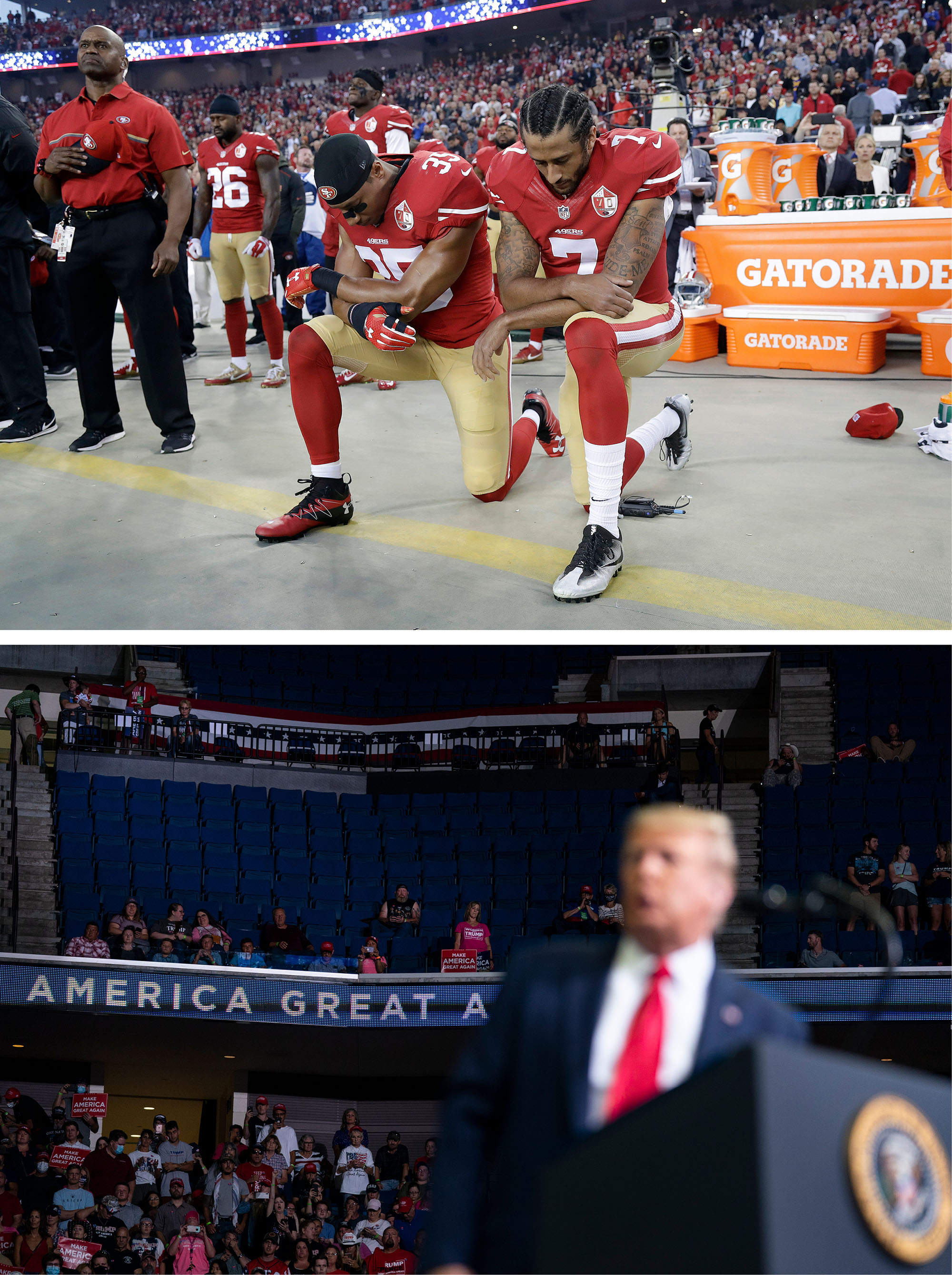

On May 25, a police officer in Minneapolis killed George Floyd by putting his knee on his neck. A week and a half later, a group of stars from the National Football League demanded that the highest officials of the nation’s biggest, richest, most popular professional sport finally listen to them—and not just listen but essentially apologize for a 2-year-old edict threatening fines for peacefully protesting by kneeling during the national anthem. They also wanted to hear specific words from league brass—condemning “racism and the systemic oppression of Black people,” admitting they were “wrong” in “silencing” them in the past and acknowledging that “Black lives matter.”

And the very next day, the commissioner of the NFL said all of that, reading practically verbatim from the players’ script and pledging that he “personally” wanted “to be part of the much-needed change in this country.” It was a striking repositioning for a hugely influential and politics-averse corporation that only a couple years back had decided that letting players kneel would risk offending millions of fans.

Donald Trump was peeved.

The kneeling policy from the NFL had been an obvious victory for him. It was Trump who had stoked the Colin Kaepernick-sparked controversy to make the 2017 season so contentious, and it was the volume of Trump’s voice, and its power, that had spurred the owners to adopt the stance they now were backing away from. Last month, then, instead of accepting the NFL’s decision to defer to its players—and to respect the dramatic, sweeping recent shift in public sentiment on matters of police brutality and racial justice—Trump opted to use his unmatched pulpit to double down. To attempt to vilify the NFL. Again.

He retweeted the husband of a senior adviser to his 2020 campaign saying he “will never buy another NFL ticket until they go back to playing football and stop dividing America.” He said he would stop watching. He told a reporter he was “very disappointed” in the league. And at his rally in that more-than-half-empty arena in Tulsa, Okla., Trump targeted the commissioner by name. “I like Roger Goodell, but I didn’t like what he said,” he told 6,200 cheering people. “We will never kneel to our national anthem or our great American flag. We will stand proud and we will stand tall.” Then he added what for the typically crowing Trump sounded almost like an admission of ground lost. “I thought,” he said, “we won that battle with the NFL.”

As this racially polarizing president revs debates about Black lives and white grievance, monuments to generals of the Confederacy and the stars and bars of the rebel flag, the American colossus of professional football, too, is sure to be a regular flashpoint of his reelection campaign in these 3½ months till November 3. The NFL has proven to be not merely the country’s largest sports entertainment property but one of its most prominent fronts of perennial culture wars as well. And if this season starts as scheduled on September 10, it almost certainly will look like no other year. Set against a backdrop of one of the most important presidential elections in the annals of a nation that’s being wracked by a world-historic pandemic, the televised games promise to produce images of kneeling players in sparsely filled stadiums, a ripe target for a president who often has been eager to pit the fortunes of the league against his own.

With Trump reeling—his approval ratings and poll numbers plunging and a growing majority of the nation increasingly skeptical that he and his administration can muster an effective response in the face of the unrelenting spread of the coronavirus—it might seem odd he’d pick this fight. For Trump, though, it’s not just about 2020, or even the past few years. It is a deeply personal feud that goes back decades.

In the 1980s, he started tangling with the NFL because he wanted to be in the NFL, looking into buying the Baltimore (not yet Indianapolis) Colts and the New England Patriots. He used his perch as the braying, impatient owner of a team in the second-rate United States Football League to spearhead a mammoth antitrust lawsuit against the NFL in a misguided attempt to force his way into the top-shelf ranks. In 2014, he tried again, and failed again, when he at least talked about proffering a (not big enough) billion-dollar bid for the Buffalo Bills. During Trump’s first fall as president, when the NFL scrambled to respond to his tweeted attacks and fretted over the loss of sponsors and fans, his swaggering new influence over the owners who repeatedly had rejected him amounted to a measure of revenge. And slides in television ratings in the 2016 and ’17 seasons plus public polling suggested some nontrivial share of viewers seemed to side with Trump.

Now, though, in the wake of the tumult of the past two months, the test for the president is whether he still has such sway—or whether the rapid change driving this unprecedented moment, evident in the players’ requests and the commissioner’s response, or public polling, or even Kaepernick’s recent deal with Disney to go with his earlier contract with Nike, means a weakened Trump is sufficiently out of step with an altered electorate and headed for defeat. It sets up a potential scenario in which maybe the final round of this long fight results in the NFL, its players, its commissioner, and its owners, too, in some sense ousting Trump from the White House.

“You can certainly look at the NFL as an indicator of where things are,” Joe Lockhart, the executive vice president of communications and public affairs for the league from 2016 to 2018 and a former press secretary for President Bill Clinton, told me—calling the NFL “one of the last purple institutions in the country.”

“In 2017, the league was very concerned about the president,” he continued. “They were very concerned that people would stop watching in the Trump base because he was making so much noise.”

That concern didn’t subside in 2018, or in 2019, or even well into this volatile year.

“In a lot of ways,” Mark Geragos, Kaepernick’s attorney, told me on June 1, even as marches, protests and post-Floyd clamor for racial justice intensified coast to coast, “Trump has more dominion and control over the NFL than Roger Goodell does.”

Last week, after the players’ video, after Goodell’s video, after six weeks of societal sea change, I called back to ask whether he still felt that way.

He didn’t have to think long. “No,” he said. “Look, they can read the writing on the wall,” Geragos said of the NFL. “This guy’s gonna lose, and he’s gonna lose big.”

“In 2017, you can make the argument that he won the first battle,” Lockhart said of Trump. “In 2020, he’s lost the war, because things have changed—and he hasn’t.”

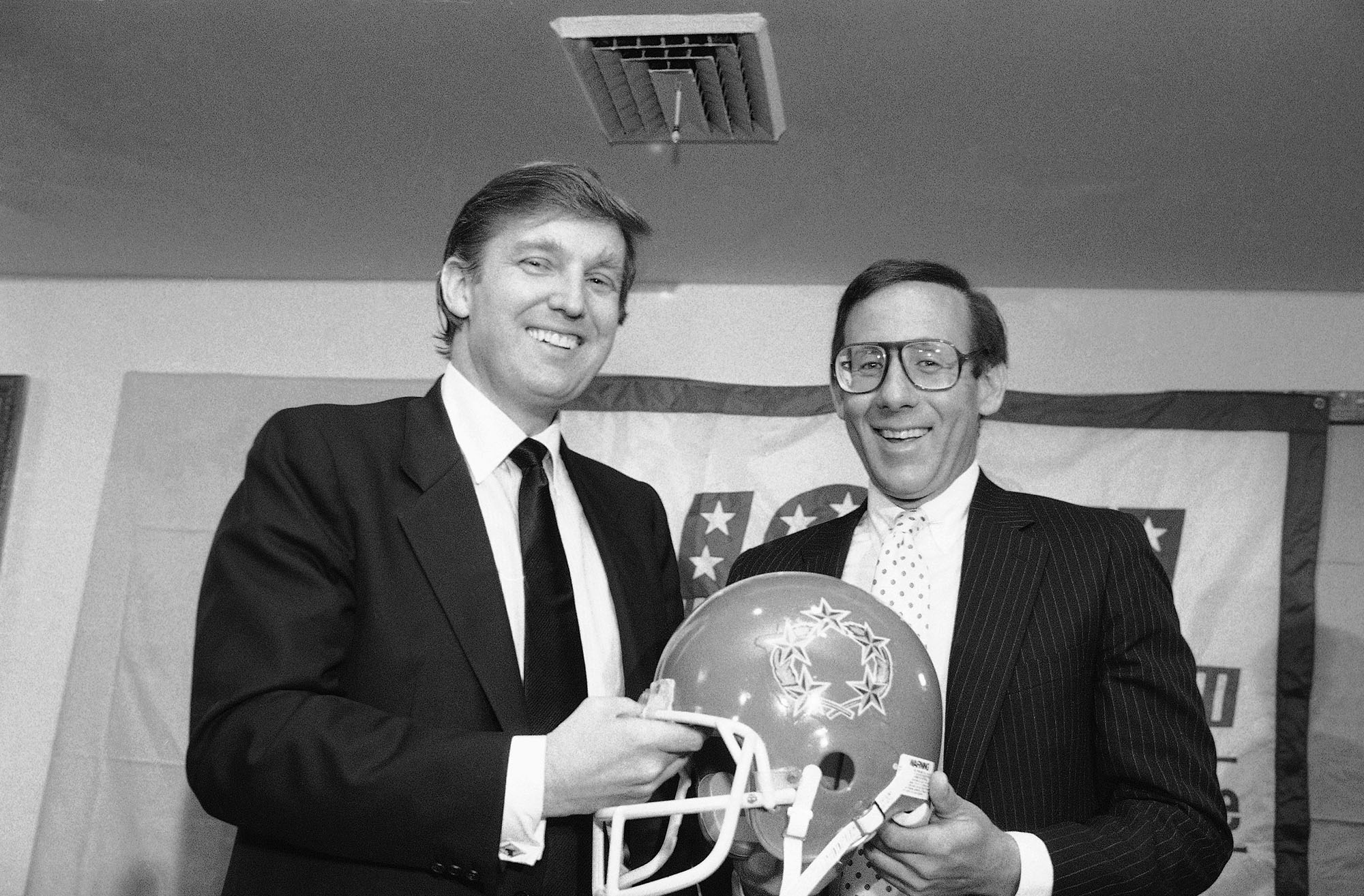

People forget, or just don’t know, but before Trump Tower, before his first divorce, and long before “The Apprentice,” football is what made Trump famous.

That was no accident. In 1983, when the 37-year-old Trump bought the year-old USFL’s New Jersey Generals, Trump sought the spotlight, and reveled in it. “He bought a team because he wants people to know who he is,” a fellow developer told Sports Illustrated. “He didn’t want to be in the Daily News’ real estate section,” said the team’s former director of public relations. “He bought himself the back page of the tabloids, the gossip pages, and then ultimately the front page,” said Charley Steiner, the team’s announcer. “Donald,” Steiner said, “wanted to be a big shot.”

What he really, really wanted, though, was to be a big shot in the NFL. “That’s where I plan on being,” he said in a meeting with his fellow USFL owners. “I could have bought an NFL team,” he told a reporter from the New York Times. “I feel sorry for the poor guy who is going to buy the Dallas Cowboys,” he added. “It’s a no-win situation for him, because if he wins, well, so what, they’ve won through the years, and if he loses, which seems likely because they’re having troubles, he’ll be known to the world as a loser.” (Jerry Jones, who purchased the Cowboys in 1989 for $140 million, owns a team now worth more than $5 billion.) “When Donald Trump came in, he was young, he was flamboyant, he was outspoken,” said an exec for the USFL. “He also made some ridiculous statements, like, ‘We can beat the NFL.’”

He tried.

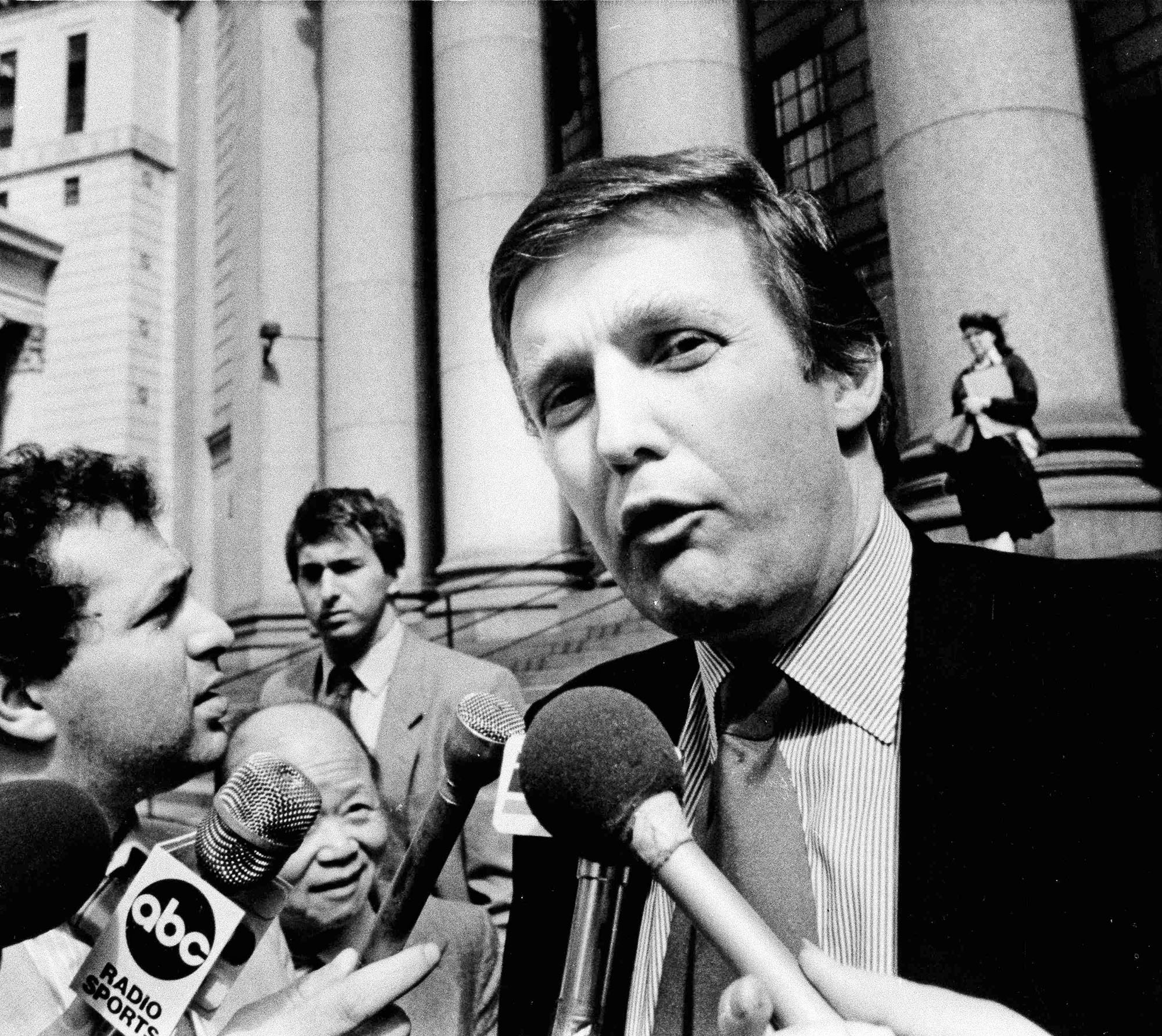

“The National Football League is the establishment, and we’re confronting it,” he said. “We’re definitely at war with the National Football League,” he said. “We’re not looking for a merger,” he said. “We’re looking for a fight.” He wanted to go right at the bigger, richer league by playing games in the fall instead of the spring. He wanted his Generals to play the NFL’s two New York teams, the Jets and the Giants, and he wanted the USFL champion to get to play the NFL champion in something he thought should be called the Galaxy Bowl. But he didn’t want to wait. And in October 1984, only a little more than a year after Trump even bought his team, the Trump-pushed USFL filed an antitrust lawsuit against the NFL alleging monopoly practices and seeking $1.69 billion.

In the sweaty summer of 1986, New York’s sports terrain ruled by the boisterous, world-champ-to-be Mets, the trial nonetheless was arresting. In the balance: the contours of professional football. “He said, ‘I want an NFL expansion team in New York,’” testified Pete Rozelle, then the commissioner of the NFL, who had kept careful notes of a meeting he had had with Trump, and at the request of Trump, two years before. “And he said,” Rozelle continued, “and I’m quoting him exactly, ‘I would get some stiff to buy the Generals.’”

The NFL’s argument was that Trump’s goal always was a backdoor merger, and that it didn’t work, and along the way he had undermined the interests of his own league. Trump, the attorney for the NFL told the jury, was a man of “effusive blind greed.”

Interestingly, after two years of litigation, more than two months of testimony and 31 hours of deliberations, the jurors decided that the NFL was in fact guilty of being a monopoly—but awarded the USFL … a dollar. Because it was an antitrust matter, that amount was tripled, resulting in a humiliating reward for a win that wasn’t a win at all. The jurors, it turned out, had agreed with the NFL’s attorney’s portrayal of Trump. The NFL’s size and its marketplace grip were hardly the source of the USFL’s demise. Trump, one juror judged, was “arrogant” and “unlikable” and “not believable in anything he said.”

A federal appeals court would concur, saying the USFL had failed on account of self-inflicted wounds. The judge singled out one owner for blame, “notably Donald Trump of the New Jersey Generals,” explaining that courts “do not exclude evidence of a victim’s suicide in a murder trial.”

Almost all of the other owners blamed Trump too. “People were fools to follow him,” said one.

He was persona non grata, too, with the NFL. “Mr. Trump,” said Rozelle, “as long as I or my heirs are involved in the NFL, you will never be a franchise owner in the league.”

“Frankly, I would’ve been better off if I’d just went in and bought an NFL team,” Trump harrumphed in 2009 in an ESPN documentary about the USFL. “It would have been a lot easier.”

No—it probably wouldn’t have.

Nearly 30 years later Trump again tried to elbow his way into the club. “People have actually talked to me about the Bills,” he told Buffalo’s WBEN radio in April 2014. “I’ll take a look at it,” he said. “I’m going to give it a heavy shot,” he said two weeks later to a reporter for the Buffalo News.

In a kind of reprise from the ‘80s, Trump plus football equaled many, many headlines and inches of copy—not just in Buffalo, not just in New York, but all over the country. The tone, though, felt at times kind of ha-ha-very-funny. “Just imagine the pregame speeches. ‘Win or you’re fired!’ a local sports columnist wrote—a reference to what had become his shockingly popular reality show catch phrase. “It might be just another Trump publicity ploy, like running for president or offering $5 million for proof Barack Obama was born on Mars,” offered one from Orlando—a reference to the racist conspiracy about the country’s first Black president that Trump had started to use to fuel his own political ascent. “Maybe,” added another one, from Arizona, “he’ll build the Bills a new stadium with a retractable comb-over top, assemble a team of cheerleaders called ‘Trump’s Exes’ and hire Rosie O’Donnell as an apprentice”—a reference to … his much-discussed hair, his record of marital failures and his penchant for petty celebrity feuds.

But newspapermen weren’t the most important people who thought this was all at best semiserious.

“NFL ownership is the most exclusive club in the world. You have to be very rich, and you have to be someone that the other owners want to welcome into the club, and Donald Trump didn’t have a chance, ever,” Lockhart, the former NFL and Clinton administration spokesman, told me this month. Three-quarters of the owners, after all, have to approve any newcomer to their ranks—and with 32 teams, that’s 24 owners. “And the owners,” Lockhart continued, “want people who are like them, but they also want people who they think they can trust, and they think will bring value, so that the league will make more money. And they sort of looked at Trump as a joke.”

I talked this week to a former NFL exec who talked to Trump that spring—“when he was, I say this word purposefully, supposedly trying to buy the Bills,” said this exec. “I very quickly felt like it was bullshit,” he told me. For starters, Trump didn’t seem to know he was going to need to put up 30 percent of the purchase price, which was expected to be $1 billion or up. “And he goes, ‘Oh, and you have to have that in cash?’” the exec recalled. “It was just obvious that he’d done nothing about it, he really didn’t know a thing, he hadn’t really thought anything through—and I was talking to him at a stage where that just made absolutely no sense.” His takeaway: “The fact that he didn’t have the resources and wasn’t a serious bidder is my conclusion from my direct conversation with him.”

And then there was the USFL stuff. “NFL owners have long memories,” one of the top New York Daily News football writers wrote. “He did try to bring the NFL down,” one of them told him.

Trump labored to try to rewrite history. “That wasn’t a Trump thing,” he said of the USFL’s yearslong, Trump-led legal assault when asked about it by the Buffalo News. “We had 12 owners and five of them couldn’t pay their bills,” he told a second football writer from the Daily News. “You cannot have a league if you have guys closing up on you and that was what was happening. And it would have happened in the spring. That’s why the league failed. It had nothing to do with Trump. In fact, I’m the reason the league was successful.”

Buffalo’s new owners, it was announced later in the year, were fracking, real estate and music moguls Kim and Terry Pegula—net worth better than $5 billion. They paid a then-NFL-record $1.4 billion. “Even though I refused to pay a ridiculous price for the Buffalo Bills, I would have produced a winner,” Trump cawed on Twitter. “Now that won’t happen.”

“He wanted to be part of the NFL club,” Jeff Pearlman, author of the 2018 book, Football for a Buck: The Crazy Rise and Crazier Demise of the USFL, told me, “because it’s a club he couldn’t get into.” And still couldn’t. He went on ESPN and said the NFL stood for “No Fun League.”

“Wow. @nfl ratings are down big league,” he tweeted that fall, during a season that ended up being to that point the second-most-watched season in league history. “Glad I didn’t get the Bills.”

There ended up, of course, being another reason as well.

“If I bought that team, I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing,” Trump said in an interview with The Associated Press in February 2016, in between the Iowa caucuses in which he finished second and the New Hampshire primary in which he finished first, at the outset of his romp toward becoming the Republican nominee.

Throughout his jagged, shambolic campaign, as his longtime Oval Office lust just got more and more real, Trump bent personal animosity for the NFL into political opportunity for himself. Into the turn-back-the-clock MAGA packaging he hawked—the U.S. doesn’t know how to win anymore, the U.S. needs to be respected again—he incorporated dated fan-boy reveries of pigskin savagery of yore.

“Who the hell wants to watch these crummy games?” he said at a rally in Reno, Nev. “What used to be considered a great tackle, a violent head-on, a violent—if that was done by Dick Butkus, they’d say he’s the greatest player—if that were done by Lawrence Taylor—it was done by Lawrence Taylor and Dick Butkus, and Ray Nitschke, right?”—ticking off the names of a New York Giants great who once signed a publicity-stunt contract with Trump’s Generals and two white NFL stars who last played in 1973—“you used to see these tackles, and it was incredible to watch, right? Now they tackle—‘Oh, head-on collision, 15 yards.’ The whole game is all screwed up. You say, ‘Wow, what a tackle.’ Bing. Flag. Football has become soft. Football has become soft. Now, I’ll be criticized for that. They’ll say, ‘Oh, isn’t that terrible.’ But football has become soft—like our country has become soft.”

That summer, though, Colin Kaepernick stayed seated on the bench during the national anthem before a preseason game. “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses Black people and people of color,” said the quarterback, who had led the 49ers to the Super Bowl four years before but by now was a backup. “This is bigger than football.”

For Trump, this was better—better fodder than belittling brain damage—and so he seized on what for him was a tailor-made chance to incite his crowds. “Maybe he should find a country that works better for him,” he said of Kaepernick in late August on a conservative talk radio show in Seattle. “The NFL is way down in their ratings,” Trump said at a rally in Colorado in late October—and this time he was right. “And you know why? Two reasons. Number one is this politics, they’re finding, is a much rougher game than football, and more exciting,” he said. “And the other reason … is Kaepernick! Kaepernick!” The people booed. “Traitor!” they yelled. “USA!” they chanted.

A week and a half later, of course, Trump won. The U.S. Senate has been called the “world’s most exclusive club,” and NFL ownership, “the Membership,” or “the 32,” as they say, is by numerical measure even more elite. But there’s only one president of this country at a time. And at least nine of the NFL’s owners ponied up a total of nearly $8 million to the committee tasked to raise money for Trump’s inauguration.

Sensing, correctly, that the balance of power between him and these owners had shifted in his favor, an emboldened Trump only escalated his Kaepernick rhetoric the first fall he was president.

In September at a rally in Alabama, he levied a new strain of assault. “Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now—out—he’s fired’ …?” he roared. The crowd responded with a crescendo of cheers. “He’s fired!”

Lockhart called Goodell early the following morning to talk about what to do. Hours later, Goodell issued a lukewarm statement labeling Trump’s comments “divisive.” It wasn’t close to enough; this was only the beginning. The next day, Trump took to Twitter to call for a boycott—a president, and a Republican to boot, employing a highly atypical tactic of interfering with private enterprise.

The NFL owners wanted no part of this—even if, as a league source said to ESPN, “they were all pissed at the president.” Even Robert Kraft, the owner of the Patriots, who considers Trump “a wonderful friend,” said he was “deeply disappointed by the tone” of his comments in Alabama. The owners of the Lions, the Dolphins, the Falcons, the Giants, the Rams and the Bills, too, made similar public censures. Jones of the Cowboys kneeled with players on his team before the playing of the national anthem, and Stephen Ross of the Dolphins locked arms with his—at first. The owners, though, quickly became “alarmed at how rapidly fans’ outrage” was “eroding many of the league’s key business metrics,” ESPN reported, and public polling showed the net favorability of the NFL dipping because of the protests—in particular among Trump voters. “This,” said an owner, “could kill football and end our business.”

Kaepernick, meanwhile, remained conspicuously unsigned.

The following spring, the NFL stiffened its anthem policy: Players could stay in the locker rooms during the national anthem; if they were out on the field in the view of the fans, however, they needed to “stand and show respect.” Teams with players that didn’t faced fines. “NFL,” read the POLITICO headline, “caves to Trump.”

“Trump,” Tim Miller, the political director of Republican Voters Against Trump, told me, “demonstrated that he wielded enormous influence over the owners around the Kaepernick controversy.”

“We already know in a situation where Colin Kaepernick could’ve actually helped some NFL teams he wasn’t re-signed,” Dave Zirin, the sports editor of The Nation, told me, “and one of the reasons for that—no question—was Donald Trump placing this social pressure, this cultural pressure, on the league.”

“He could make life miserable for them,” Geragos, Kaepernick’s attorney, told me. And he did. “The league,” Lockhart added, “was well aware that a tweet might be coming at any time.”

“This is a very winning, strong issue for me,” Trump told the Cowboys’ Jones in a phone call, according to Jones’ deposition in Kaepernick’s lawsuit that accused the league of colluding to nix his career. “Tell everybody,” Trump told Jones, meaning all the other owners, “you can’t win this one. This one lifts me.”

Now, though, the NFL could help sink him.

Trump wants the NFL, the institution besides the start of school that tells the country it’s fall, to play its games as slated—“needs it,” national sports columnist Dan Wetzel told me—to foster any semblance of normalcy for citizens addled with anxiety, and perhaps to provide some vague collective psychic boost during the run-up to Election Day, with as ever a certain portion of voters making their choices based on how they feel more than what they might or might not know. In April, less than a month after the World Health Organization declared the outbreak of the novel coronavirus a pandemic, the president said he thought the NFL season should start on time. A few weeks ago, when Anthony Fauci sounded notes of skepticism about the league’s ability to play games safely, Trump lashed back. “Tony Fauci,” he tweeted, “has nothing to do with NFL Football.” He retweeted himself some 8½ hours later.

“It is a very important physical and emotional touch point for whether the nation starts to feel normal again,” Ari Fleischer, the former White House press secretary for George W. Bush, told me. He likened it to the wake of September 11, 2001, and the lift of the return of sports back then. “Its absence was discernible, and we intuitively understood that once it came back, the country feels better.”

“The president wants them to play because sport, again, reflects the general character, status, circumstances and so forth of the society,” Harry Edwards, the eminent sociologist, civil rights activist and expert on the experience of the Black athlete, told me. “If there’s no football season—if there’s no basketball season, if the college football ranks are not active—this is going to be another mark against his leadership.”

“If there’s no NFL,” Trump biographer Michael D’Antonio told me, “then that’s like a natural disaster for his base. And it’ll be because he didn’t make coronavirus go away.”

More broadly, though, but equally concerning for Trump, is the reality that the culture-war currents on which he’s staked such visceral claims are moving, and fast, in ways that for him don’t bode well.

Kaepernick has now inked deals with two of the NFL’s biggest partners in Nike and Disney. The Washington Redskins are changing their name. Elsewhere on the sports scene, NASCAR, an outfit practically synonymous with America’s South, banned the Confederate flag at its events. And in this roiling, potent aftermath of the killing of George Floyd, star players of the NFL in the video said enough was enough. “I am George Floyd,” said DeAndre Hopkins. “I am Breonna Taylor,” said Jamal Adams. “I am Ahmaud Arbery,” said Eric Kendricks. “I am Eric Garner,” said Ezekiel Elliot. “I am Laquan McDonald,” said Sterling Shepard. “I am Tamir Rice,” said Patrick Mahomes. “I am Trayvon Martin,” said Marshon Lattimore. And so it went, on and on. And then Roger Goodell said what he said—the commissioner, who says nothing of the sort without the backing of a sufficient share of the owners for whom he works, and by whom he’s paid.

“I can say this with high confidence. He’s not out there saying that without having reviewed with certain owners if they’re OK with him saying it,” the former NFL exec told me. “That’s telling—and obviously a significant change.”

Goodell, in the estimation of the exec, was speaking to different audiences—with Trump at the top of the list.

“He kind of sent him a warning: ‘Listen, we’re going to handle things differently now. So, if you want to fight, come on; if you don’t, you know, we’re fine with the status quo—but we’re not going to just sit here and take it again.’”

The president thought he had this won. He said so in Tulsa. And he did have the upper hand in ’16 and ’17. But TV ratings for the NFL went back up in ’18 and then again last year. And now more and more fans support kneeling, according to public polling, siding with the players instead of the president—his approval rating plummeting, including with respect to how he’s “handling race relations.” And yet he has described civil rights protesters as “thugs” and dredged retrograde phrases and disseminated racist invective and dismissed disproportionate Black deaths at the hands of police.

“Colin,” Geragos, Kaepernick’s attorney, told me last week, “was ahead of his time. And now people see that everything he said was in some ways prophetic. The country’s changed.”

“The equation for them,” the former NFL exec said of the owners vis-à-vis Trump, “has flipped from ‘taking him on is more costly than beneficial to taking him on is more beneficial than costly.’ I don’t think you’ll see a lot of public confrontation, but I think you’ll see them take actions, like we saw Goodell do like a month ago, that show a little bit more boldness and a little less acquiescence.

“I mean, at some point, people who are—and I’m using this word loosely—but who are bullied are fearful, and at some point they realize—you know what?—the bully is just kind of an empty suit.”

“Trump spent whatever it was, 20 years”—more than 30, actually—“trying to show the world that he could be part of this club, that he was a real American businessman, and all the things he was trying to do, and it failed across the board, because he wasn’t who he said he was,” Lockhart told me. “And all of a sudden he gets elected and he has leverage. And it takes him a little while to figure it out, and he realizes, ‘Well, I can bring these guys to their knees.’ Now, I don’t think he brought them to their knees, but he certainly had an influence, and I think he felt pretty good about that. And I think he looked at the current situation and said, ‘OK, we’re going to try to do this again.’ And I think he has misread the situation, just like I think right now he’s misreading the country.

“What Trump doesn’t realize,” he said, “is that the world has moved on. I guarantee you that the players will kneel—and that the NFL will say it’s OK. And it doesn’t matter this time what Donald Trump says.”

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream