The Trump administration’s pledge to protect Covid-19 patients from massive medical bills is falling short for a growing number of survivors who experience long-term complications from the virus.

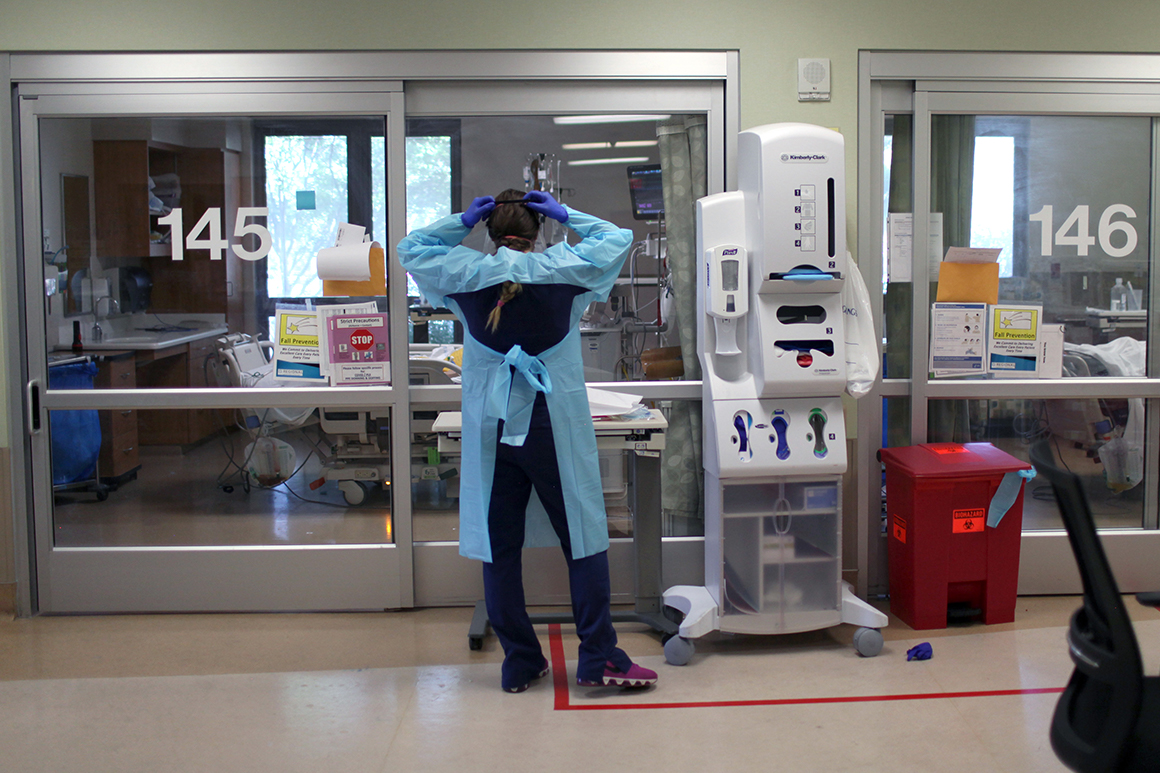

Doctors are discovering life-threatening and costly long-term health effects ranging from kidney failure to heart and lung damage. That’s exposing a major gap in the federal government’s strategy for ensuring patients won’t go broke because of a coronavirus diagnosis.

Patients with and without insurance have already been hit with staggering bills, despite a White House promise to cover their costs, according to patient advocates. That’s because health care providers and insurers are classifying some complications as distinct from the virus during the billing process. The extent of the problem is still not fully known due to the lag time in settling medical claims.

Private health insurers, including many the White House prodded to waive full treatment costs for patients diagnosed with coronavirus, haven’t committed to extending those generous coverage policies to patients dealing with virus-related conditions weeks or months later. Some that only cover in-network care are rejecting bills from out-of-network specialists.

Insurers like Cigna are waiving costs for these post-viral health problems — but only as long as the patients’ doctors explicitly link them to Covid-19 on their medical bills. Patients whose doctors fail to may be exposed to staggering charges: One woman reported getting at least $65,000 in bills for an eight-day stay in the hospital for Covid-19 and complications that included a colon infection.

The payment policies also may not help people who had coronavirus symptoms early during the pandemic but couldn’t get tested — or who experienced symptoms mild enough not to even try. The bills and ongoing cost of care for these individuals can be massive if they develop heart inflammation, kidney disease, or other serious problems that doctors have observed for months.

“The death toll, as devastating as it is, is a small part of the whole story, because you don’t know what the disability toll is,” said James DeLemos, chair in cardiology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Health providers eager for payment are lobbying the Trump administration to start paying for uninsured patients’ post-coronavirus care using a hospital bailout fund. Facilities that get paid can’t turn around and try to collect more money from the patients.

But the Health Resources and Services Administration that runs the fund says it will only pay if Covid-19 is the patient’s primary diagnosis. Molly Smith, a vice president at the American Hospital Association, calls the requirement “flawed,” and warns the government won’t pay for a “significant” amount of coronavirus treatment as a result.

A spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services declined to say whether the administration is talking to health plans about a solution. The government hasn’t issued guidance on billing for post-virus conditions, citing ongoing ongoing research and the many unknowns about the long-term effects of Covid-19.

A HRSA spokesperson said as long as the program requirements are met, treatment of a stroke or other complication will get covered — but reiterated that Covid-19 needs to be the primary diagnosis.

It will take years to document the long-term effects of the novel coronavirus, but early signs have been alarming. One study of hospitalized patients in Wuhan, China, found that nearly 20 percent of those with confirmed cases suffered heart injury.

Some of the treatment costs worry patient advocates and policymakers. Charges for a six-day hospital stay for a coronavirus patient with an underlying health condition or complications average more than $74,000 according to FAIR Health, a nonprofit that analyzes claims data, although commercial plans would pay an average of just under $39,000 for the treatment. Cases with fewer complications would still incur charges averaging more than $53,000 for a six-day stay.

The consulting firm Avalere recently projected that a typical hospital stay for coronavirus patients is nearly $23,500. But insurers still don’t have a clear picture of potential long-term costs, especially if patients need long rehab after weeks on ventilators, or dialysis if they suffer kidney failure.

“We still don’t know the disease from the clinical side, we don’t know the complications and we don’t know it on the claims side,” said one insurance lobbyist.

DeLemos calls the range of post-viral problems a “desperate area,” in which very little is known about what happens to survivors once they’re discharged. The same goes for the overwhelming majority of Covid-19 survivors who never were hospitalized and don’t know if they’ll experience long-term health effects.

“Some had a mild lung condition and then got a very serious heart complication,” he said. “The only thing I can say is that the most predictable thing about Covid is its unpredictability.”

The dearth of data makes policy-making difficult. Paul Auwaerter, clinical director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Johns Hopkins University, noted people who were healthy before Covid-19 and are now suffering new health problems may blame the virus for unrelated conditions. Only better data and analysis will resolve questions.

“People tend to anchor on the last thing that hit them, so as more time goes on, people will turn to Covid, but it’s not always the answer,” he said.

Meanwhile advocates wary of costs being shifted on unsuspecting patients are watching for all the ways complications will hit Americans during the pandemic.

“Having done this for 25 years, when we hear the governors say, If you need health care you can get it, it’s just not our experience,” said Michele Johnson, executive director of the Tennessee Justice Center, referring to the White House promise that all uninsured patients are covered. She noted that it’s hard for many patients to get through the door for medical treatment, including even Covid-19 testing, if they don’t have coverage.

Cynthia Fisher, founder of the nonprofit Patient Rights Advocate, lambasted insurers and hospitals alike for the high medical bills she’s seen from Covid-19, noting that health plans have been making money throughout the pandemic, since most people put off going to their doctors but still are paying premiums. And overall, a minority of Covid-19 patients are getting hospitalized with serious problems.

“It’s just the right thing to do to cover their care, because the insurance companies have been prepaid for this, and yet they’re not actually covering the people who have paid for coverage,” Fisher said. “We’re just seeing the insurers are capitalizing on the pandemic.”

Meanwhile, the existing pledges to cover people’s treatment could end if the Trump administration refuses to extend its public health emergency for the pandemic, which is due to expire next month.

On Tuesday, the administration gave health plans wide berth if they want to back out of their pledges to fully cover coronavirus treatment once the emergencies are lifted. Instead of the 60-day warning usually required to make policy changes, health insurers can drop the enhanced benefits with “reasonable” notice, or simply when the declaration expires if they’ve informed customers.

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream