Voters in deep-red Oklahoma this week could order Medicaid expansion for at least 200,000 poor adults, defying state and Trump administration officials fighting to limit the Obamacare program.

If voters approve a ballot measure on Tuesday, Oklahoma would become the first state to broadly expand government-backed health insurance to many of its poorest residents since the beginning of a pandemic that has stripped many people of coverage. At the same time, that could scuttle the Trump administration’s efforts to make Oklahoma a test case for its plan to transform the entitlement program into a block grant.

While ballot measures on Medicaid expansion in recent years have succeeded in other Republican strongholds like Idaho, Nebraska and Utah, the Oklahoma vote comes at a volatile time. Republican Gov. Kevin Stitt is warning the program would be unaffordable while the state suddenly confronts an estimated $1.3 billion shortfall. Voter turnout is also in question as infection rates surge and the state braces for the possibility of cases stemming from President Donald Trump’s recent rally in Tulsa. At least eight Trump staffers working the event last weekend have tested positive for the virus.

The ballot measure would extend coverage to poor adults without children earning just about $17,000 per year. Many of them have limited affordable coverage options, since they earn too little to qualify for subsidies to purchase health insurance on the Obamacare marketplace. Supporters believe the rise in urgent medical needs during the pandemic will help convince voters to approve it, though there’s limited reliable polling before the vote.

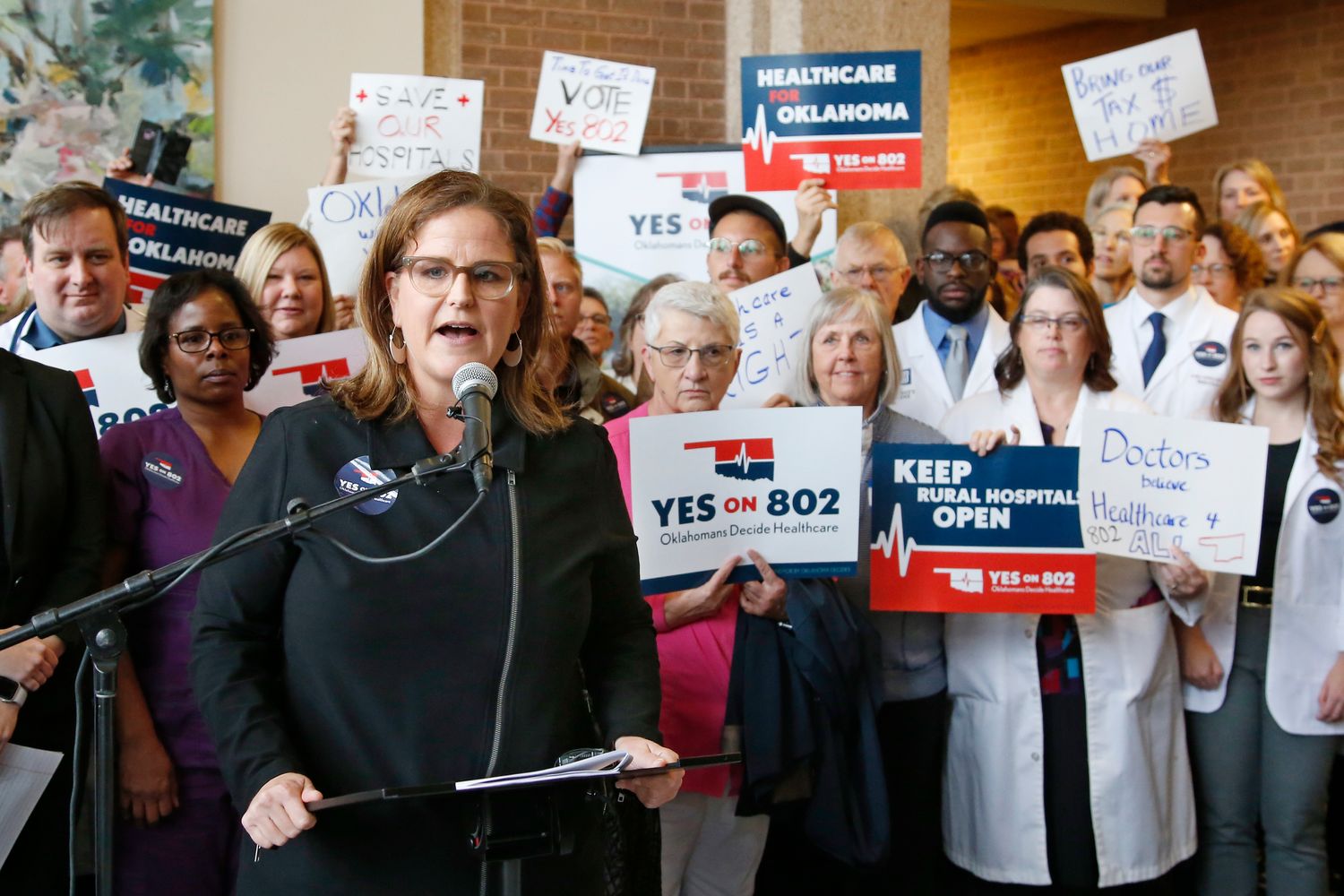

“In terms of the pandemic, now more than ever people understand that when you need health care, you need it now,” said Amber England, the campaign manager behind the ballot measure.

Backers of the measure have adjusted their campaign to the coronavirus era — hosting socially distanced events like virtual phone banks and happy hours over Zoom — but they’re sticking with messages that resonated with voters in previous expansion referendums. Campaign organizers, who’ve spent nearly $2 million on advertising, according to Advertising Analytics, have largely emphasized how Medicaid expansion would improve access to health care.

Oklahoma, one of 14 mostly Republican-led states where officials have long refused Obamacare’s optional Medicaid expansion, has the nation’s second worst uninsured rate at more than 14 percent, behind only Texas. That number seems poised to climb higher with the state’s unemployment rate surging to nearly 13 percent in recent months.

If the ballot measure succeeds, it would represent a major win for Democrats, who have been frustrated by the lack of a nationwide effort to expand coverage during the worst public health crisis in a century. The Trump administration has rejected calls to expand health insurance and is still pressing the Supreme Court to overturn Obamacare. Meanwhile, the economic fallout from the crisis has prompted other states with Democratic governors to halt major coverage expansions. California Gov. Gavin Newsom paused plans to extend coverage to undocumented seniors, while a deal Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly struck with a key Republican lawmaker to expand Medicaid is on hold.

The opposition to the Oklahoma ballot initiative is being led by the Oklahoma chapter of Americans for Prosperity, a Koch brothers-backed conservative group that recently launched a six-figure digital ad and direct mail campaign arguing that expansion would bankrupt the state. During a virtual event hosted by the group this week, Stitt said the state’s coronavirus-related budget crunch would make it impossible to pay for Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion without raising taxes or cutting services like education or infrastructure.

“The money doesn’t just appear,” said Stitt, who last month vetoed a bill that would have helped partially pay for the state’s share of Medicaid expansion costs by boosting a fee on hospitals. Stitt said the levy wouldn’t provide a reliable long-term funding stream for the coverage program.

Medicaid expansion supporters in Oklahoma argue the program would bring desperately needed federal support for the state’s long-struggling rural hospitals, which have taken a further hit by a dropoff in elective procedures after the coronavirus emerged. Since 2016, six of the state’s hospitals have closed and another eight have declared bankruptcy.

“We simply can’t afford not to” expand coverage, said Oklahoma House Minority Leader Emily Virgin, a Democrat.

The outcome of the Oklahoma ballot measure will be closely watched in Missouri, where voters on Aug. 4 will also vote on expanding Medicaid in their state. The ballot measure is strongly opposed by Gov. Mike Parson, a Republican facing reelection in November. Organizers of the Missouri ballot measure have similarly focused their messaging on the plight of the state’s hospitals, particularly those in rural areas. Ten hospitals have closed in Missouri since 2014, according to the state’s hospital association.

“It’s about making sure Missourians can access health care in their communities,” said Jack Cardetti, a spokesperson for the group behind the ballot initiative.

Expansion supporters are also watching how Oklahoma’s growing coronavirus infection rates affect voting. The state’s election board is advising — but not requiring — poll workers and voters to wear masks. Mail-in balloting is also broadly allowed, but election law experts said state requirements that they be notarized or come with a copy of government-issued identification could depress turnout, particularly in low-income communities who’d directly benefit from expansion.

“Unless you’re able to fill in the ballot at your kitchen table and put it in the mailbox, anything more than that is going to be more difficult,” said Joseph Anthony, a visiting assistant professor at Oklahoma State University who specializes in elections and voting rights. “All of these things are onerous."

Jan Largent, the president of the state’s League of Women Voters, said four times the usual number of absentee ballots have been requested for the June 30 vote, when the state’s primary election is also being held.

“People are determined to get out and vote for 802,” she said, referring to the ballot question number.

The ballot measure, if successful, could block Stitt from pursuing the Trump administration’s proposal to install strict funding caps for the first time in Medicaid’s 55-year history. Ballot organizers designed the measure so it would add Medicaid expansion to the state’s constitution, believing that would bar Republican officials from adding conservative elements to the program as state lawmakers in Utah and Idaho did after voters overwhelmingly approved expansion in 2018.

Oklahoma was the first state to sign up for Trump’s new plan to convert the federal government’s open-ended Medicaid payments into a lump sum, known as the block grant. Trump’s proposal would still require states to expand Medicaid to low-income adults, but in a way that could be more palatable to conservatives who’ve sought to control program spending. Democrats have fiercely opposed the administration’s plan, which they say is illegal and could force states to make cuts in enrollment or health care services during tough economic times.

Stitt’s own position on Medicaid has shifted. He had once opposed Medicaid expansion, but then came to support the Trump administration’s block grant plan announced earlier this year. Weeks later, he announced Oklahoma would implement traditional Medicaid expansion this summer, even while the Trump administration reviewed his block grant plan. The move raised suspicion among expansion supporters that Stitt was trying to undercut their ballot initiative since it could invalidate the block grant plan, but Oklahoma officials said expanding early would ease the state’s transition to a block grant.

But Stitt a few weeks ago scrapped plans to immediately expand Medicaid, saying the pandemic added an unexpected financial strain on the state. Meanwhile, he’s still asking the Trump administration to approve his block grant proposal.

Carter Kimble, Stitt’s health deputy secretary, said Oklahoma wouldn’t necessarily withdraw the block grant plan if the ballot initiative passes.

“It’s a legal question and we’ll play by the rules,” Kimble said. “But I think that there is some space for some legal conversations about what our options are.”

Source: politico.com

See more here: news365.stream